Robert Boyd

People should get paid for their work. That's the basic premise behind Working Artists and the Greater Economy (W.A.G.E.). Their mission is a little less blunt:

In the world of commercial art, the Graphic Artists Guild publishes a book called Graphic Artist's Guild Handbook of Pricing and Ethical Guidelines![]() . Commercial artists are in a similar situation as fine artists--they are freelance and they usually have many clients.This book gives them an idea of what they should charge for their work. Without this, they'd just have to guess what a fair price is and be more vulnerable.

. Commercial artists are in a similar situation as fine artists--they are freelance and they usually have many clients.This book gives them an idea of what they should charge for their work. Without this, they'd just have to guess what a fair price is and be more vulnerable.

Now the presence of the Graphic Artists Guild and the Handbook doesn't mean that artists don't get ripped off or exploited. But it helps artists understand when they are getting ripped off and provides tools for artists to avoid it.

How is W.A.G.E. approaching this issue? Mainly be going straight to the non-profits (501(c)3 tax exempt arts organizations) and providing a certification program. It involves changing their budgets (both annual and for specific exhibits/events) to reflect ethical pricing, as defined by W.A.G.E.'s fee calculator. So if a non-profit is W.A.G.E.-certified, an artist knows that there is a certain floor for her fee (and visitors know that the artists got paid fair fees). The fee calculator is based on the organization's total annual operating budget. I wish W.A.G.E. had defined this better. For example, would G&A expenses or depreciation count in your operating budget? I suspect it's different for non-profits than for commercial enterprises, but I'm not sure exactly how.

My problem with certification is that it only really provides a binary tool for artists--either the institution that may host your exhibit is certified or not. So it occurred to me that the expenses of any given 501(c)3 organization are public--they report them on their 990 tax forms, which anyone can access via Guidestar. If you look at the "Total Expenses" line of an organization's 990, the vast majority of that should be operational expenses. (If it's not, then I suspect that there's something wrong with the organization.) So I thought, let's use reported 990 expenses as a stand-in for total annual operating budget. Given this, what should artists be getting paid by various Houston area art non-profits? (In reality, the W.A.G.E. minimum fee will be slightly lower for some of the institutions once you take out the non-operational part of the expenses.)

![]()

* Assumed the written piece was 1100 words

** Assumed 3 hours of labor

There's a lot of information here. The left hand column are the institutions in question, in descending order by total expenses. The second column is the source of the total expenses number. The third column is the total expenses for each institution. The remaining columns are the minimum level fees for a variety of artistic activities recommended by W.A.G.E. using their fee calculator.

Some institutions are not shown because they are not 501(c)3s and therefore do not publish their 990s (the Station Museum and the Art Car Museum, for example). Some art institutions are part of larger institutions so I can't separate out their finances (the Rice Gallery, the Blaffer Museum, the Contemporary Art Gallery and the Fine Museum at HBU, the University Museum at TSU and the various galleries at HCC and Lone Star Community College campuses).

W.A.G.E. also has a maximum level of pay: "At the maximum rate, or 'Maximum W.A.G.E.' compensation at the Solo Exhibition rate is capped at the average salary of the institution's full-time employees." But since I don't have that information, I have left those figures off.

The first thing you notice is that for any institution with less than $500,000 in annual expenses, the fees are all the same. This is W.A.G.E.'s floor level. For operating expenses between $500,000 and $5 million, the fees are generally a percentage of the operating expenses. Above $5 million, the minimum is capped (as you can see for the HAA, the Menil and the MFAH). These fees do not include expenses such as travel, lodging and shipping. The institution is expected to cover such expenses above and beyond the basic fee, and W.A.G.E. provides guidelines for that.

I think this could be a useful took for artists. Even if an institution is not W.A.G.E. certified, it at least gives an artist an idea of what they should be asking for for their services.

Are their problems with W.A.G.E. and their approach? Yes. I had a long conversation the other day about this and several issues arose. To simplify, here are the questions that came up and here's how I (obviously not a spokesman for W.A.G.E.) would answer them.

1) Doesn't this commodify a relationship that is about much more than money?

Yes. This is always a cost in labor agreements. The question has to be what is lost versus what is gained.

2) Doesn't the floor price mean something different in different places? $1000 in New York City is different from $1000 in Houston, for example.

I think this is a serious issue. Was W.A.G.E. thinking primarily of their home base in New York when they came up with the floor pricing? If so, maybe there should be a scale based on relative cost-of-living for a given location. Obviously doing so would make the fee calculator much more complicated--and therefore less easy to use. But perhaps W.A.G.E. believes that this floor should be national in the same way that, say, the federal minimum wage is national.

3) Isn't W.A.G.E. too militant? Isn't their tone off-putting?

The history of labor rights won is not a history of asking politely. That said, for all of W.A.G.E.'s radical bluster, they don't suggest any consequences for 501(c)3s not getting certified. For example, are they suggesting that artists boycott especially egregious institutions? Picket them?

4) Doesn't this turn non-profit organizations into "the Man"?

Yes, in the sense that it formalizes the freelance relationship between artist and institution. But 501(c)3s are already formalized institutions in a legal sense. They aren't ad hoc spaces--they've gone through the trouble to become tax-exempt organizations with charitable purpose. We hold them to account, and asking that they pay decent fees is just one more example of this public accounting. The details of the fee calculator can be argued, but expecting everyone to come through in at least some minimal way doesn't seem unreasonable to me.

5) Doesn't the fee calculator, and particularly the "floor," penalize very small art organizations?

I think so. Box 13, with its annual budget of $85 thousand, is not in a position to pay every artist with a solo show $1000. This small artist-run institution exists mainly to provide inexpensive studio space (it was founded by artists who were evicted from the original CSAW). As far as I know, they have no paid staff. But they host some of the most interesting shows in Houston. Is it reasonable to expect the same pay rate from them as from Lawndale, which has more than five times Box 13's budget?

These issues will, I assume, be open for discussion at charge, a two-day practicum at the Art League. on November 8 and 9. Alas, I will be traveling that week, so I'll miss it. It will feature a variety of speakers and seminar leaders from both the local scene and from around the country, including Lise Soskolne from W.A.G.E. If you're planning to attend, think about spending some quality time with the 990s of Houston's various art non-profits. I know it sounds boring, but if you are thinking of exhibiting with any of them, you owe it to yourself to know something about their finances.

Have you had an exhibit with any of the institutions above? How much did they pay you? If you're willing to come forward, I think it would be very useful for other artists to know. Let us know in the comments section below.

People should get paid for their work. That's the basic premise behind Working Artists and the Greater Economy (W.A.G.E.). Their mission is a little less blunt:

Founded in 2008, Working Artists and the Greater Economy (W.A.G.E.) is a New York-based activist group whose advocacy is currently focused on regulating the payment of artist fees by nonprofit art institutions and establishing a sustainable model for best practices between artists and the institutions that contract their labor.The labor of artists for nonprofit art institutions is different from other kinds of labor. It's freelance instead of on-going. But it's not work-made-for-hire--the institution doesn't own the work unless a specific purchase agreement is made. Nonetheless, I think we can all agree that when an artist puts on an exhibit in some non-profit space, some work is done. If it's a show of paintings, most of the work is embedded in the paintings themselves, which the artist can subsequently sell. If it's a site-specific temporary installation, the artist has no hope of gaining future income from the work. Given this, it seems fair that these two artists be paid different fees. But the question is, how do you determine the fees?

In the world of commercial art, the Graphic Artists Guild publishes a book called Graphic Artist's Guild Handbook of Pricing and Ethical Guidelines

. Commercial artists are in a similar situation as fine artists--they are freelance and they usually have many clients.This book gives them an idea of what they should charge for their work. Without this, they'd just have to guess what a fair price is and be more vulnerable.

. Commercial artists are in a similar situation as fine artists--they are freelance and they usually have many clients.This book gives them an idea of what they should charge for their work. Without this, they'd just have to guess what a fair price is and be more vulnerable.Now the presence of the Graphic Artists Guild and the Handbook doesn't mean that artists don't get ripped off or exploited. But it helps artists understand when they are getting ripped off and provides tools for artists to avoid it.

How is W.A.G.E. approaching this issue? Mainly be going straight to the non-profits (501(c)3 tax exempt arts organizations) and providing a certification program. It involves changing their budgets (both annual and for specific exhibits/events) to reflect ethical pricing, as defined by W.A.G.E.'s fee calculator. So if a non-profit is W.A.G.E.-certified, an artist knows that there is a certain floor for her fee (and visitors know that the artists got paid fair fees). The fee calculator is based on the organization's total annual operating budget. I wish W.A.G.E. had defined this better. For example, would G&A expenses or depreciation count in your operating budget? I suspect it's different for non-profits than for commercial enterprises, but I'm not sure exactly how.

My problem with certification is that it only really provides a binary tool for artists--either the institution that may host your exhibit is certified or not. So it occurred to me that the expenses of any given 501(c)3 organization are public--they report them on their 990 tax forms, which anyone can access via Guidestar. If you look at the "Total Expenses" line of an organization's 990, the vast majority of that should be operational expenses. (If it's not, then I suspect that there's something wrong with the organization.) So I thought, let's use reported 990 expenses as a stand-in for total annual operating budget. Given this, what should artists be getting paid by various Houston area art non-profits? (In reality, the W.A.G.E. minimum fee will be slightly lower for some of the institutions once you take out the non-operational part of the expenses.)

W.A.G.E. Fee Calculator Applied to Annual Expenses of Houston-Area Art Non-Profits

* Assumed the written piece was 1100 words

** Assumed 3 hours of labor

There's a lot of information here. The left hand column are the institutions in question, in descending order by total expenses. The second column is the source of the total expenses number. The third column is the total expenses for each institution. The remaining columns are the minimum level fees for a variety of artistic activities recommended by W.A.G.E. using their fee calculator.

Some institutions are not shown because they are not 501(c)3s and therefore do not publish their 990s (the Station Museum and the Art Car Museum, for example). Some art institutions are part of larger institutions so I can't separate out their finances (the Rice Gallery, the Blaffer Museum, the Contemporary Art Gallery and the Fine Museum at HBU, the University Museum at TSU and the various galleries at HCC and Lone Star Community College campuses).

W.A.G.E. also has a maximum level of pay: "At the maximum rate, or 'Maximum W.A.G.E.' compensation at the Solo Exhibition rate is capped at the average salary of the institution's full-time employees." But since I don't have that information, I have left those figures off.

The first thing you notice is that for any institution with less than $500,000 in annual expenses, the fees are all the same. This is W.A.G.E.'s floor level. For operating expenses between $500,000 and $5 million, the fees are generally a percentage of the operating expenses. Above $5 million, the minimum is capped (as you can see for the HAA, the Menil and the MFAH). These fees do not include expenses such as travel, lodging and shipping. The institution is expected to cover such expenses above and beyond the basic fee, and W.A.G.E. provides guidelines for that.

I think this could be a useful took for artists. Even if an institution is not W.A.G.E. certified, it at least gives an artist an idea of what they should be asking for for their services.

Are their problems with W.A.G.E. and their approach? Yes. I had a long conversation the other day about this and several issues arose. To simplify, here are the questions that came up and here's how I (obviously not a spokesman for W.A.G.E.) would answer them.

1) Doesn't this commodify a relationship that is about much more than money?

Yes. This is always a cost in labor agreements. The question has to be what is lost versus what is gained.

2) Doesn't the floor price mean something different in different places? $1000 in New York City is different from $1000 in Houston, for example.

I think this is a serious issue. Was W.A.G.E. thinking primarily of their home base in New York when they came up with the floor pricing? If so, maybe there should be a scale based on relative cost-of-living for a given location. Obviously doing so would make the fee calculator much more complicated--and therefore less easy to use. But perhaps W.A.G.E. believes that this floor should be national in the same way that, say, the federal minimum wage is national.

3) Isn't W.A.G.E. too militant? Isn't their tone off-putting?

The history of labor rights won is not a history of asking politely. That said, for all of W.A.G.E.'s radical bluster, they don't suggest any consequences for 501(c)3s not getting certified. For example, are they suggesting that artists boycott especially egregious institutions? Picket them?

4) Doesn't this turn non-profit organizations into "the Man"?

Yes, in the sense that it formalizes the freelance relationship between artist and institution. But 501(c)3s are already formalized institutions in a legal sense. They aren't ad hoc spaces--they've gone through the trouble to become tax-exempt organizations with charitable purpose. We hold them to account, and asking that they pay decent fees is just one more example of this public accounting. The details of the fee calculator can be argued, but expecting everyone to come through in at least some minimal way doesn't seem unreasonable to me.

5) Doesn't the fee calculator, and particularly the "floor," penalize very small art organizations?

I think so. Box 13, with its annual budget of $85 thousand, is not in a position to pay every artist with a solo show $1000. This small artist-run institution exists mainly to provide inexpensive studio space (it was founded by artists who were evicted from the original CSAW). As far as I know, they have no paid staff. But they host some of the most interesting shows in Houston. Is it reasonable to expect the same pay rate from them as from Lawndale, which has more than five times Box 13's budget?

These issues will, I assume, be open for discussion at charge, a two-day practicum at the Art League. on November 8 and 9. Alas, I will be traveling that week, so I'll miss it. It will feature a variety of speakers and seminar leaders from both the local scene and from around the country, including Lise Soskolne from W.A.G.E. If you're planning to attend, think about spending some quality time with the 990s of Houston's various art non-profits. I know it sounds boring, but if you are thinking of exhibiting with any of them, you owe it to yourself to know something about their finances.

Have you had an exhibit with any of the institutions above? How much did they pay you? If you're willing to come forward, I think it would be very useful for other artists to know. Let us know in the comments section below.

" It's a wall between the viewer and experiencing the art. This viewer, at least.

" It's a wall between the viewer and experiencing the art. This viewer, at least.

, the first major new work by Charles Burns since

, the first major new work by Charles Burns since  . Right away, the cover was promising--it was a pastiche of sorts of Hergé's

. Right away, the cover was promising--it was a pastiche of sorts of Hergé's  . Instead of setting it on a rocky shore, Burns set it in a grey, bombed out landscape. Burn's "Tintin" was a character drawn in a classic "realistic" comics style with a bandage on his head. But the pattern on the ovoid shape in the foreground was unmistakable--it was the same as the coloring of the mushroom in The Shooting Star.

. Instead of setting it on a rocky shore, Burns set it in a grey, bombed out landscape. Burn's "Tintin" was a character drawn in a classic "realistic" comics style with a bandage on his head. But the pattern on the ovoid shape in the foreground was unmistakable--it was the same as the coloring of the mushroom in The Shooting Star.

, we see Doug's future self talking about the past. He goes from being a slim student to packing on a few pounds. But the time he is with Sarah is when he seems to be a physical peak. They are a beautiful couple and his later self is full of regret about what happened to them, which he knows but we don't.

, we see Doug's future self talking about the past. He goes from being a slim student to packing on a few pounds. But the time he is with Sarah is when he seems to be a physical peak. They are a beautiful couple and his later self is full of regret about what happened to them, which he knows but we don't.

, which just came out, completes the story. All the flashbacks and disconnected episodes in Doug's life coalesce, and the parallel Burns-Hergé world makes sense as well. If there is any fault here, it's that everything is tied up a little too neat. But I found it satisfying. Doug turns out to be a pretty imperfect guy who stumbles badly as he transitions into adulthood and leaves behind some unrepairable wreckage. This is the kind of story an older person can tell convincingly. Burns was born in 1955. I wrote

, which just came out, completes the story. All the flashbacks and disconnected episodes in Doug's life coalesce, and the parallel Burns-Hergé world makes sense as well. If there is any fault here, it's that everything is tied up a little too neat. But I found it satisfying. Doug turns out to be a pretty imperfect guy who stumbles badly as he transitions into adulthood and leaves behind some unrepairable wreckage. This is the kind of story an older person can tell convincingly. Burns was born in 1955. I wrote  . The health of comics as an art form depends on having several generations of serious comics artists working simultaneously.

. The health of comics as an art form depends on having several generations of serious comics artists working simultaneously.

, a collection of stories from 1986 to 2012. I've read many of these stories before in the various ephemeral publications where they first ran, but it quite astonishing to see them in one place. It is interesting to see how constant his themes and subjects have remained over the course of almost 30 years of work.

, a collection of stories from 1986 to 2012. I've read many of these stories before in the various ephemeral publications where they first ran, but it quite astonishing to see them in one place. It is interesting to see how constant his themes and subjects have remained over the course of almost 30 years of work.

. (Full disclosure--I own two pages from this work.) And you can see his mastery of this art form blossom during the 90s in the stories here.

. (Full disclosure--I own two pages from this work.) And you can see his mastery of this art form blossom during the 90s in the stories here.

, will be published later this year, and you can read most of it online right now at Horrock's website

, will be published later this year, and you can read most of it online right now at Horrock's website

Back to Max Bill, I see the format as a visual drift-off whereas rectangular/squares are constraining.

Back to Max Bill, I see the format as a visual drift-off whereas rectangular/squares are constraining.

the classic on perception which I give all my Perspective Drawing students,

the classic on perception which I give all my Perspective Drawing students,  by Carl Sagan, Michio Kaku’s

by Carl Sagan, Michio Kaku’s  as well as Brian Greene’s

as well as Brian Greene’s  The painting Systems A-GO-GO is based on Mario Livio’s

The painting Systems A-GO-GO is based on Mario Livio’s  Forgive me for listing books like a pretentious ass but a Houston Press writer used innuendo to snicker at my naming my painting after

Forgive me for listing books like a pretentious ass but a Houston Press writer used innuendo to snicker at my naming my painting after

The Miraculous consists of 50 chapters, mostly pretty short, describing the way an artist has come up with a particular artwork--usually a conceptual artwork or a performance. Depending how familiar you are with the world of performance art and conceptual art, you will recognize some of these. And as I read, I noticed that chapter 22 described the bizarre time-passing activity of Percival Bartlebooth, the character from Georges Perec's novel,

The Miraculous consists of 50 chapters, mostly pretty short, describing the way an artist has come up with a particular artwork--usually a conceptual artwork or a performance. Depending how familiar you are with the world of performance art and conceptual art, you will recognize some of these. And as I read, I noticed that chapter 22 described the bizarre time-passing activity of Percival Bartlebooth, the character from Georges Perec's novel,  That made me smile, because when I read that novel so very long ago, I thought that the fictional Bartlebooth's absurd life-long project was basically an insane work of art. And it was enough that Perec described its execution--it didn't have to actually be done to be real. And that could apply to any number of the pieces or actions described in this book. The fact that they were actually executed is, well, miraculous.

That made me smile, because when I read that novel so very long ago, I thought that the fictional Bartlebooth's absurd life-long project was basically an insane work of art. And it was enough that Perec described its execution--it didn't have to actually be done to be real. And that could apply to any number of the pieces or actions described in this book. The fact that they were actually executed is, well, miraculous. came out.

came out.

But the bloom is off that rose, as we've seen in the recent recession. Creative people don't get paid much and are as likely to be exploited now as ever. And we'll never need as many creative people as we once needed factory workers. Those guys stamping out boxes for Nilla Wafers in Beacon and fabricating boilers at Pioneer Iron Works were contributing to an economy that brought more people up from poverty than any other ever did (at least, until China's recent economic opening).

But the bloom is off that rose, as we've seen in the recent recession. Creative people don't get paid much and are as likely to be exploited now as ever. And we'll never need as many creative people as we once needed factory workers. Those guys stamping out boxes for Nilla Wafers in Beacon and fabricating boilers at Pioneer Iron Works were contributing to an economy that brought more people up from poverty than any other ever did (at least, until China's recent economic opening).

In Bedazzled, Peter Cook's Satan character was pranking people to provoke anger, one of the seven deadly sins. In Devil's Slice of Life, Barbatos gets paid for his work. I'd describe it as a cute-brut-style comic--Barbatos (and his victims and fellow devils) are drawn in a deliberately rough style, but it maintains a kind of manga-influenced cuteness. Devil's Slice of Life was printed in three colors on a risograph, which is a popular printing platform for small-press and self-published comics. Crotty is a member of a Dutch artists' studio called

In Bedazzled, Peter Cook's Satan character was pranking people to provoke anger, one of the seven deadly sins. In Devil's Slice of Life, Barbatos gets paid for his work. I'd describe it as a cute-brut-style comic--Barbatos (and his victims and fellow devils) are drawn in a deliberately rough style, but it maintains a kind of manga-influenced cuteness. Devil's Slice of Life was printed in three colors on a risograph, which is a popular printing platform for small-press and self-published comics. Crotty is a member of a Dutch artists' studio called

, collecting together art by H.C. Westermann, Jim Nutt, Peter Saul, Ken Price, Mike Kelley, Jim Shaw, Jim Drain, William Copley, Elizabeth Murray, Jack Kirby, Gary Panter and many more, is an equivalent to the rock nerds' challenge to the accepted history of rock. The grand narrative Nadel is challenging is the canonical history of art from the 60s through the 90s. You might think of this history as appropriation and assemblage paralleled by minimalism, post-minimalism transitioning to conceptualism, installation and performance, heavily undergirded by French theory as filtered through Artforum and October. Establishing a counterhistory to that seems like a worthwhile thing to do, right?

, collecting together art by H.C. Westermann, Jim Nutt, Peter Saul, Ken Price, Mike Kelley, Jim Shaw, Jim Drain, William Copley, Elizabeth Murray, Jack Kirby, Gary Panter and many more, is an equivalent to the rock nerds' challenge to the accepted history of rock. The grand narrative Nadel is challenging is the canonical history of art from the 60s through the 90s. You might think of this history as appropriation and assemblage paralleled by minimalism, post-minimalism transitioning to conceptualism, installation and performance, heavily undergirded by French theory as filtered through Artforum and October. Establishing a counterhistory to that seems like a worthwhile thing to do, right?

and

and  and

and  . What Nerve! brings together a lot of artists who have long been objects of fascination for Nadel as well as the idea of an alternate to the canon.

. What Nerve! brings together a lot of artists who have long been objects of fascination for Nadel as well as the idea of an alternate to the canon.

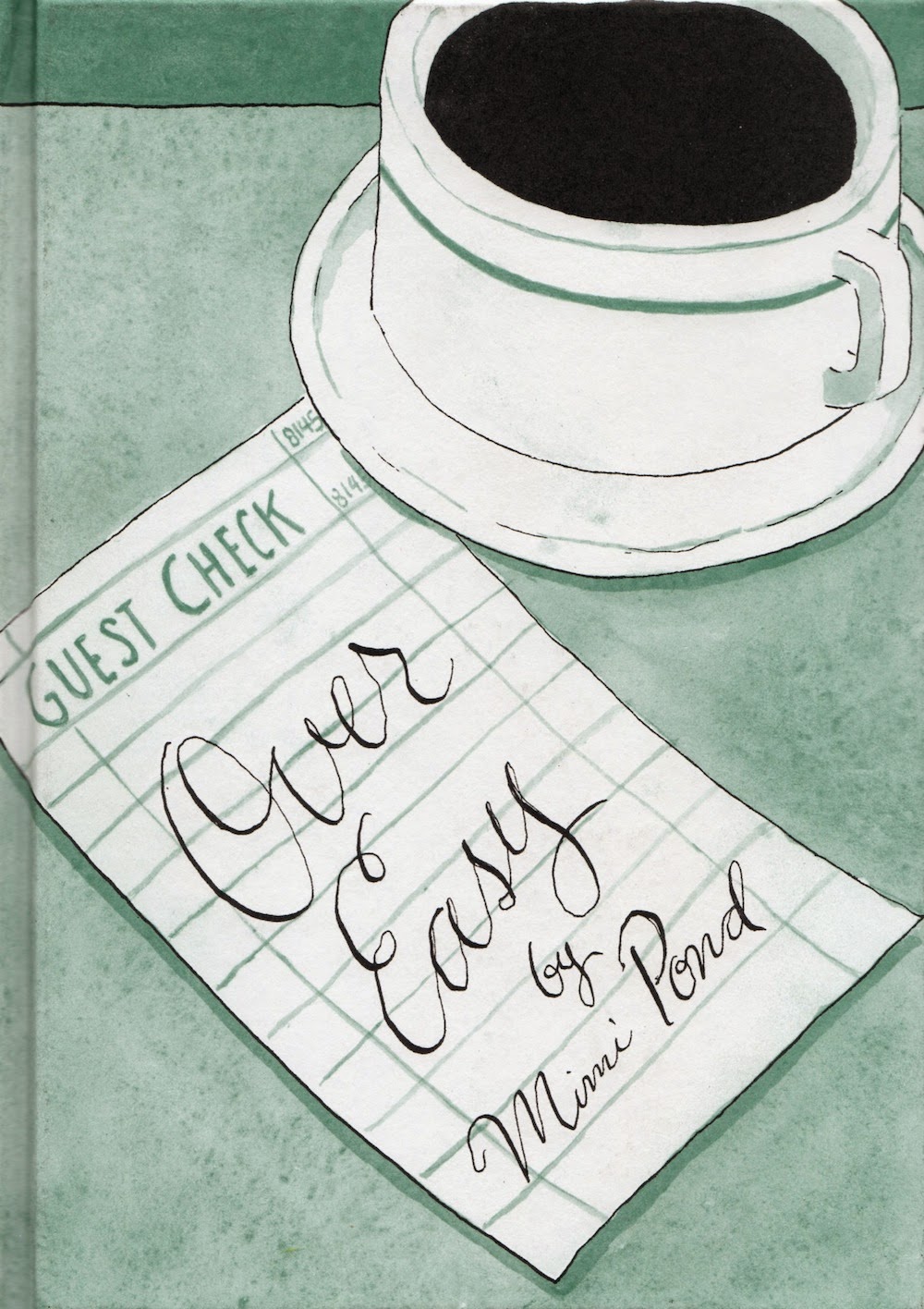

was published in 2008. It was a success for two reasons, I think. One, it treated the art world as its subject rather than particular artists or exhibits. Of course she wasn't the first to do this.

was published in 2008. It was a success for two reasons, I think. One, it treated the art world as its subject rather than particular artists or exhibits. Of course she wasn't the first to do this.  (1982) by Howard Becker looked at the art world in a broader sense than Thornton did, and in pain-staking detail. Gary Alan Fine examined the world of outsider art in

(1982) by Howard Becker looked at the art world in a broader sense than Thornton did, and in pain-staking detail. Gary Alan Fine examined the world of outsider art in  (2004). All three writers are sociologists, which makes their interest in art more than just an interest in aesthetics--they want to know about the range of activities and people involved in this space.

(2004). All three writers are sociologists, which makes their interest in art more than just an interest in aesthetics--they want to know about the range of activities and people involved in this space. is the answer. When I heard the title, I was worried that Thornton had abandoned her sociological background and was going to write just about a collection of individuals. But she has placed them to various degrees in a world of friends, colleagues, helpers and family--in short, she is not doing

is the answer. When I heard the title, I was worried that Thornton had abandoned her sociological background and was going to write just about a collection of individuals. But she has placed them to various degrees in a world of friends, colleagues, helpers and family--in short, she is not doing  , where he quotes

, where he quotes

. He wrote:

. He wrote:

by Katie Robinson Edwards tells the story of how modern art came to Texas.

by Katie Robinson Edwards tells the story of how modern art came to Texas.

by Roz Chast (Bloomsbury USA). Long my favorite New Yorker cartoonist, this lengthy work on a serious subject is miraculously both moving and hilarious. She can't stop being

by Roz Chast (Bloomsbury USA). Long my favorite New Yorker cartoonist, this lengthy work on a serious subject is miraculously both moving and hilarious. She can't stop being  by Joyce Farmer and

by Joyce Farmer and

by Richard McGuire (Pantheon Books). This is the most formally daring of all the comics I've listed. Each page is a double spread, facing into the corner of a nondescript room, with a window on the left and a fireplace on the right. In the upper left-hand corner of each page is a year, like 2014 or 1956 or 1775 or even 3,000,500,000 BCE. And what you see in the spread is what you would be seeing at some point in that year. So we see the house being built in 1907, and we see the large house across the street being built in 1764. We see the forest before then inhabited by Native Americans who come into contact with Dutch settlers, and we see prehistoric landscapes. And we see a future, which at first seem fairly hightech. One image from 2213 shows a tour guide using a device that allows the tourists to see what we're seeing in Here--the house that stood on that spot throughout the years. But we also see a very distant future that seems devoid of humanity. We even have a guest appearance by Benjamin Franklin, who visits the colonial house which is, apparently, where his son lives. And all these different views are shown in non-chronological order.

by Richard McGuire (Pantheon Books). This is the most formally daring of all the comics I've listed. Each page is a double spread, facing into the corner of a nondescript room, with a window on the left and a fireplace on the right. In the upper left-hand corner of each page is a year, like 2014 or 1956 or 1775 or even 3,000,500,000 BCE. And what you see in the spread is what you would be seeing at some point in that year. So we see the house being built in 1907, and we see the large house across the street being built in 1764. We see the forest before then inhabited by Native Americans who come into contact with Dutch settlers, and we see prehistoric landscapes. And we see a future, which at first seem fairly hightech. One image from 2213 shows a tour guide using a device that allows the tourists to see what we're seeing in Here--the house that stood on that spot throughout the years. But we also see a very distant future that seems devoid of humanity. We even have a guest appearance by Benjamin Franklin, who visits the colonial house which is, apparently, where his son lives. And all these different views are shown in non-chronological order.

by Jaime Hernandez (Fantagraphics Books). This collects several related stories from Love & Rockets.

by Jaime Hernandez (Fantagraphics Books). This collects several related stories from Love & Rockets.

by John Porcellino (Drawn & Quarterly). Starting in 1997,

by John Porcellino (Drawn & Quarterly). Starting in 1997,

by Abel Lanzac and Christophe Blain (SelfMadeHero).

by Abel Lanzac and Christophe Blain (SelfMadeHero).

by Sam Alden (Uncivilized Books).

by Sam Alden (Uncivilized Books). by Jean-Pierre Filiu and David B. (SelfMadeHero). Not quite as good as the first volume, but still good. These books feature rather didactic texts, but the text is enlivened by the fertile visual imagination of David B, one of the greatest cartoonists alive.

by Jean-Pierre Filiu and David B. (SelfMadeHero). Not quite as good as the first volume, but still good. These books feature rather didactic texts, but the text is enlivened by the fertile visual imagination of David B, one of the greatest cartoonists alive. by Peter Bagge (Fantagraphics).

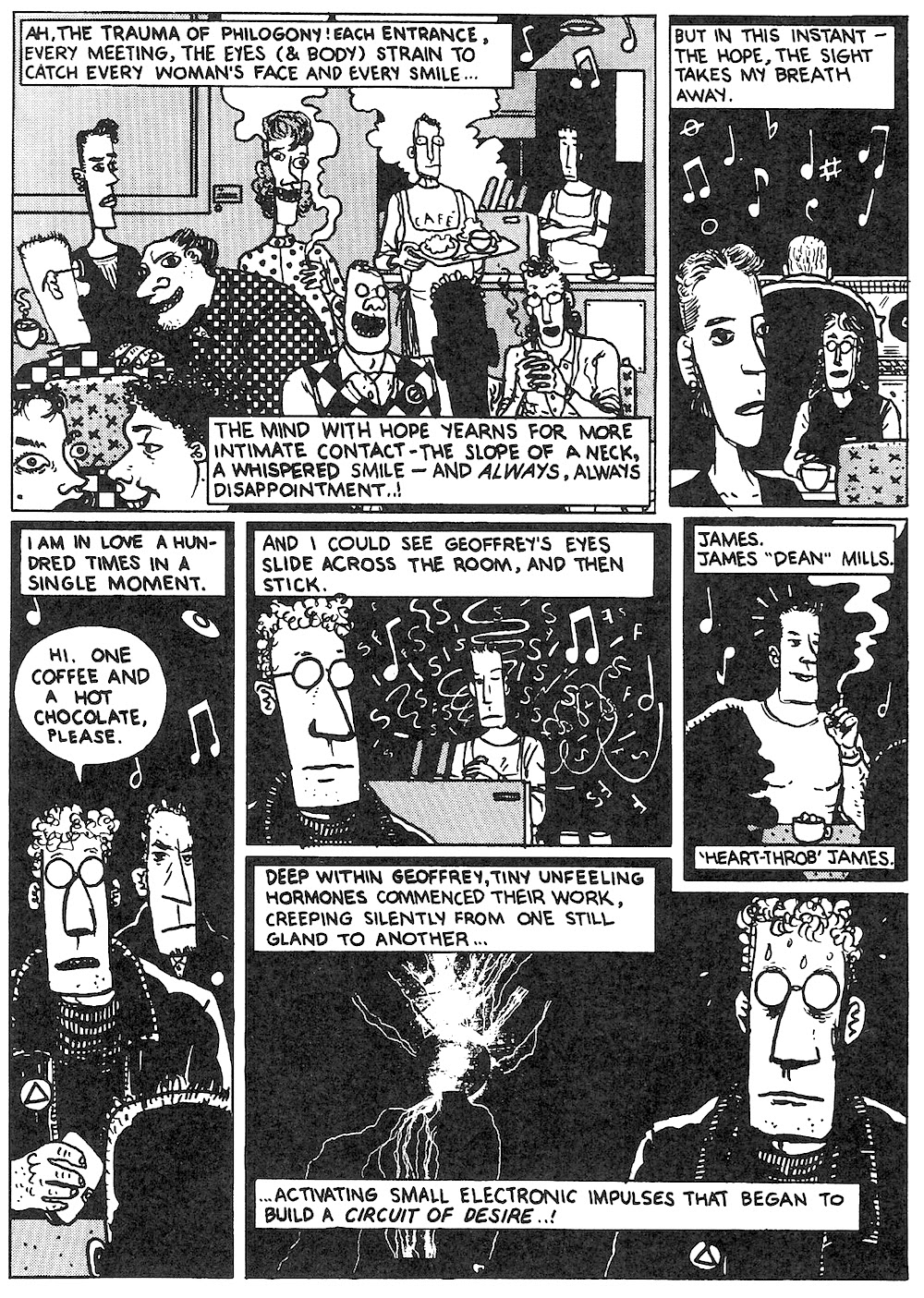

by Peter Bagge (Fantagraphics).  by Jimmy Beaulieu (Conundrum Press). It starts off as a "meet cute" romantic comedy, but My Neighbor's Bikini is actually quite sexy. It has a down-to-earth eroticism that is emphasized by Beaulieu's beautiful pencil drawing.

by Jimmy Beaulieu (Conundrum Press). It starts off as a "meet cute" romantic comedy, but My Neighbor's Bikini is actually quite sexy. It has a down-to-earth eroticism that is emphasized by Beaulieu's beautiful pencil drawing. by Gabrielle Bell (Uncivilized Books).

by Gabrielle Bell (Uncivilized Books).  by Eleanor Davis (Fantagraphics Books). Beautifully drawn, these stories range from dramatic to humorous, but all told from the point of view of the modern person who is into yoga, worried about wheat allergies, etc. I'm not even sure what to call this vast subculture--but I like the way Davis circles around and through it, dealing with its absurdities and beauties.

by Eleanor Davis (Fantagraphics Books). Beautifully drawn, these stories range from dramatic to humorous, but all told from the point of view of the modern person who is into yoga, worried about wheat allergies, etc. I'm not even sure what to call this vast subculture--but I like the way Davis circles around and through it, dealing with its absurdities and beauties.  by Mike Dawson (Secret Acres). An intriguing story that combines left wing street politics with frustrated romance in an unexpected way. Discussion of Dawson and this book lead to

by Mike Dawson (Secret Acres). An intriguing story that combines left wing street politics with frustrated romance in an unexpected way. Discussion of Dawson and this book lead to  by Bob Fingerman (Image Comics). The first version of Minimum Wage (collected as

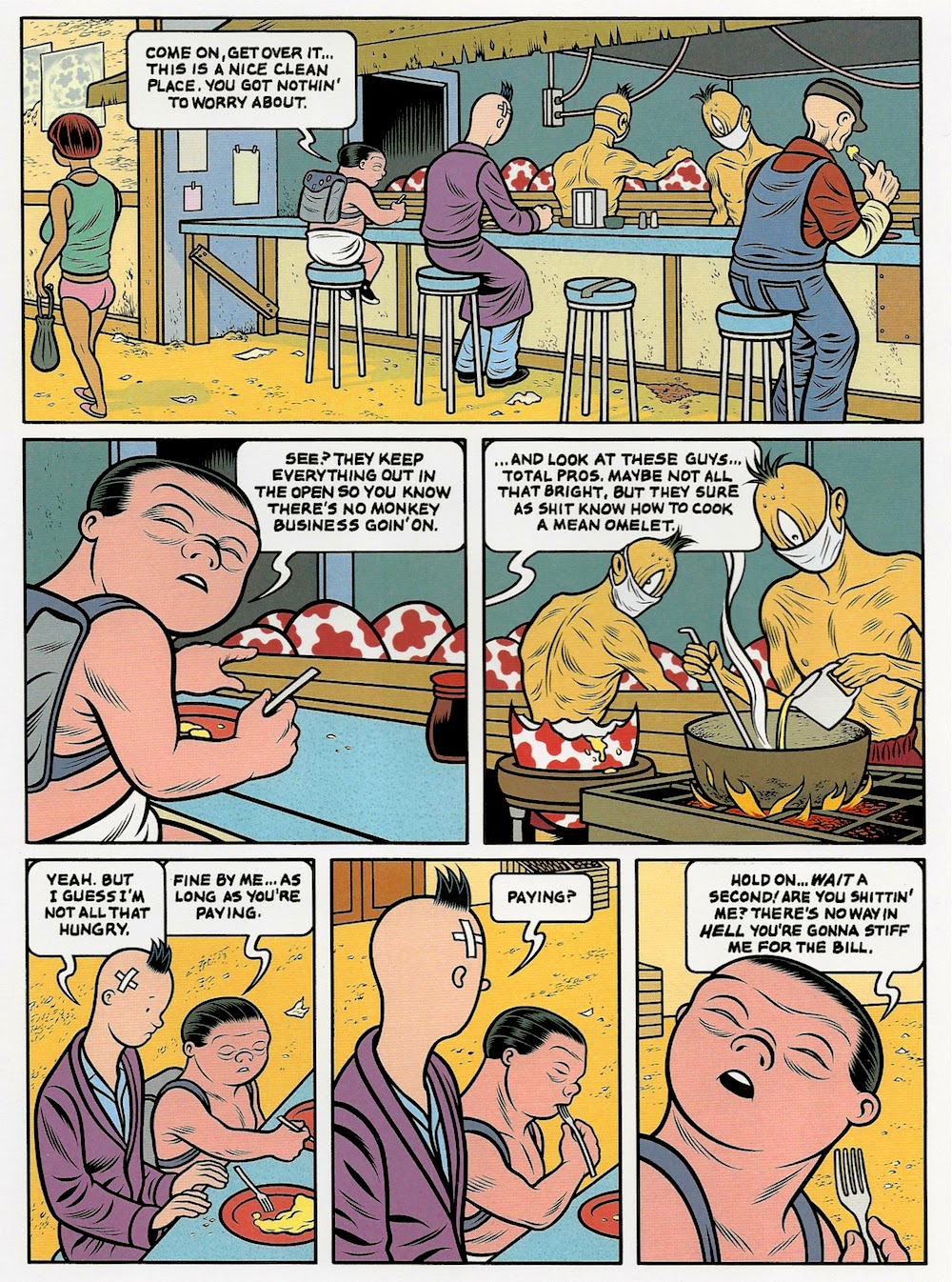

by Bob Fingerman (Image Comics). The first version of Minimum Wage (collected as ) found Fingerman loosening up from his earlier art style and getting into a funny roman à clef. (I was even drawn into the background of one scene!) But this new Minimum Wage series is so much better--his drawing amazingly continues to improve with age and the dialogue feels less written and more lived.

) found Fingerman loosening up from his earlier art style and getting into a funny roman à clef. (I was even drawn into the background of one scene!) But this new Minimum Wage series is so much better--his drawing amazingly continues to improve with age and the dialogue feels less written and more lived.  by Simon Hanselmann (Fantagraphics Books). By all accounts, Simon Hanselmann is a workaholic. Funny then that his primary subject is the lives of a household of lazy stoners. The work captures the repetitiveness of the stoner life perfectly, and is hilarious.

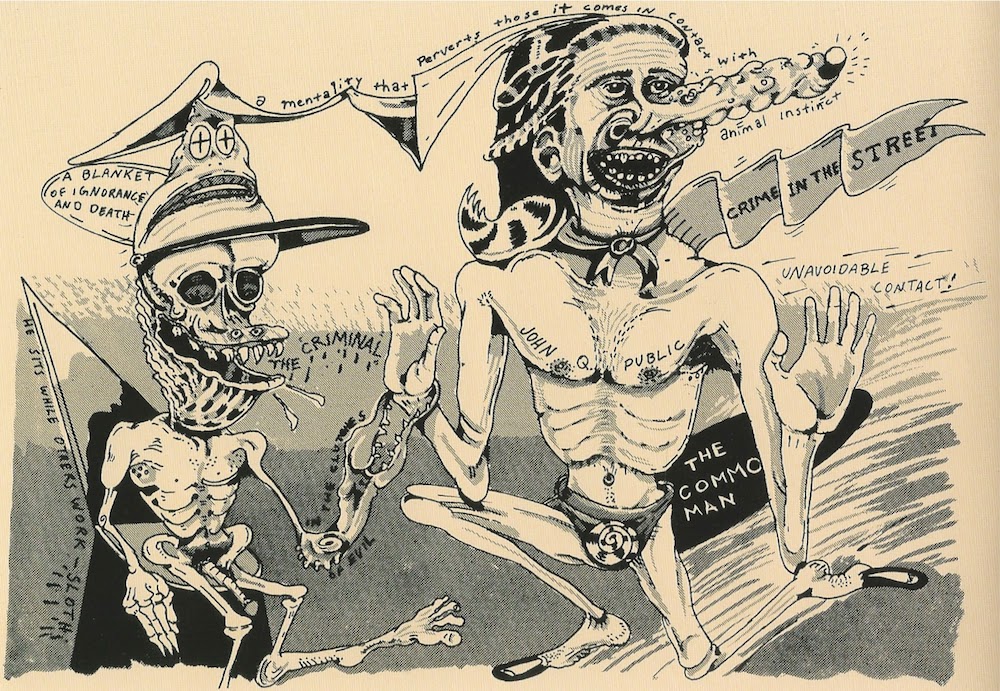

by Simon Hanselmann (Fantagraphics Books). By all accounts, Simon Hanselmann is a workaholic. Funny then that his primary subject is the lives of a household of lazy stoners. The work captures the repetitiveness of the stoner life perfectly, and is hilarious. edited by Peter Kuper and Seth Tobocman, featuring work by Kuper, Tobocman, Eric Drooker, Sabrina Jones, Sue Coe, Chuck Sperry and many more (PM Press). I really beautifully produced "best of" collection of the venerable left-wing political comic that has been published continuously since 1980.

edited by Peter Kuper and Seth Tobocman, featuring work by Kuper, Tobocman, Eric Drooker, Sabrina Jones, Sue Coe, Chuck Sperry and many more (PM Press). I really beautifully produced "best of" collection of the venerable left-wing political comic that has been published continuously since 1980. by Shigeru Mizuki (Drawn & Quarterly). Mizuki's history is eccentric and depends heavily on photo references, but the parallel stories of his own life as a young soldier in the Imperial Japanese Army are amazing.

by Shigeru Mizuki (Drawn & Quarterly). Mizuki's history is eccentric and depends heavily on photo references, but the parallel stories of his own life as a young soldier in the Imperial Japanese Army are amazing. by Jesse Moynihan (Nobrow Press). This volume was not quite as engaging as volume 1 because the story (by necessity) slowed down a bit. Volume 1 spent a lot of time putting the chess pieces in place. Forming II is showing us how the game is playing out.

by Jesse Moynihan (Nobrow Press). This volume was not quite as engaging as volume 1 because the story (by necessity) slowed down a bit. Volume 1 spent a lot of time putting the chess pieces in place. Forming II is showing us how the game is playing out. by Fabian Vehlman and Kerascoët (Drawn & Quarterly). A very strange story set amongst the fairies and insects of a forest, in a surprisingly violent fantasy world. Beautifully drawn but disturbing.

by Fabian Vehlman and Kerascoët (Drawn & Quarterly). A very strange story set amongst the fairies and insects of a forest, in a surprisingly violent fantasy world. Beautifully drawn but disturbing. by Jim Woodring (Fantagraphics Books). Collecting all the comics and 'zines that were published under the moniker "Jim" (and a few odds and ends from elsewhere), this is some of Woodring's finest, most oneiric work.

by Jim Woodring (Fantagraphics Books). Collecting all the comics and 'zines that were published under the moniker "Jim" (and a few odds and ends from elsewhere), this is some of Woodring's finest, most oneiric work.  by Mickey Zacchilli (Youth in Declne). Scratchy, urgent graphics combined with an absurd, funny, pulpy story.

by Mickey Zacchilli (Youth in Declne). Scratchy, urgent graphics combined with an absurd, funny, pulpy story.