Robert Boyd

I'm still trying to catch up blogging about comics I've read this summer. You can see more reviews here as well as my guide to Jesse Moynihan's Forming. This time around, I'm looking at some comics from Argentina, Belgium, France and Japan. Aside from their shared non-American origins, they don't have anything in common. Or one could say that the only things they have in common are things they lack--there are no superheroes in these books, no fights between good and evil, etc. This doesn't mean that they're good. Your mileage may vary. Mine did.

![]()

Macanudo #1![]() (Enchanted Lion Books, 2014) by Liniers. Liniers is the pen-name for Ricardo Siri, creator of the daily comic strip Macanudo. He and his wife also run a small publishing house called La Editorial Común, which publishes some very high quality Argentine, European and North American alternative comics. His drawing style is excellent, and his strips have great "timing." He often employs "silent" panels to provide a "rest" in the rhythm of the gag. Because are stand-alone strips, the gag is important. Liniers humor is more wry than laugh-out-loud funny. Many of his strips involve taking classic, cliched humor situations and tweaking them (as in the two examples below).

(Enchanted Lion Books, 2014) by Liniers. Liniers is the pen-name for Ricardo Siri, creator of the daily comic strip Macanudo. He and his wife also run a small publishing house called La Editorial Común, which publishes some very high quality Argentine, European and North American alternative comics. His drawing style is excellent, and his strips have great "timing." He often employs "silent" panels to provide a "rest" in the rhythm of the gag. Because are stand-alone strips, the gag is important. Liniers humor is more wry than laugh-out-loud funny. Many of his strips involve taking classic, cliched humor situations and tweaking them (as in the two examples below).

![]()

![]()

My problem with Linier's comics is that they really aren't all that funny. They're a little funny, sure. I don't hate them--I just don't love them. But I think that a kid, maybe 10 or 11, might find these hilarious the same way I found, say, B.C. hilarious at that age. So perhaps I'm the wrong audience for Macanudo. In any case, one can't deny that it's a very well-crafted comic strip.

![]()

White Cube![]() (Drawn & Quarterly, 2014) by Brecht Vandenbroucke. This seemed right up my alley--comics about art and the art world. The title refers to the classic modernist white cube

(Drawn & Quarterly, 2014) by Brecht Vandenbroucke. This seemed right up my alley--comics about art and the art world. The title refers to the classic modernist white cube![]() gallery (as well as the well-known contemporary art gallery, White Cube). White Cube stars two identical male protagonists who look at art, buy art and make art with absurd results. The style of the art and the humor recalls the classic Belgian comic CowboyHenk by Kamagurka and Herr Seele. But unfortunately, White Cube is far inferior to Cowboy Henk.

gallery (as well as the well-known contemporary art gallery, White Cube). White Cube stars two identical male protagonists who look at art, buy art and make art with absurd results. The style of the art and the humor recalls the classic Belgian comic CowboyHenk by Kamagurka and Herr Seele. But unfortunately, White Cube is far inferior to Cowboy Henk.

![]()

Brecht Vandenbrouke, White Cube p. 25

This witless and cruel joke typifies much of what is in the book. It's nasty without being funny. It seems almost unfair to mention it in relation to Cowboy Henk. Here's a Cowboy Henk strip for comparison.

![]()

(from Smoke Signal, Desert Island's in-house comics tabloid.)

Only one Cowboy Henk book has been published in English,Cowboy Henk: King of Dental Floss, and that was way back in 1994. Yes to Kamagurka and Herr Seele; no to Brecht Vandenbroucke!

![]()

Weapons of Mass Diplomacy![]() (SelfMadeHero, 2014) by Abel Lanzac and Christophe Blain. This is a rather bizarre book, but I found it captivating. Lanzac is the pen-name of a French diplomat, Antonin Baudry. Baudry worked for the French Foreign Minister, Dominique de Villepin during the run-up to the Iraq War, and France was being hectored by the U.S. to join its "coalition of the willing." France wisely chose not to participate in this foolish war. Now one might expect someone like Baudry to write a memoir of the experience. What no one would expect is that he would fictionalize it in a graphic novel, Quai d'Orsay (retitled Weapon of Mass Diplomacy for English speaking readers). In the book, the low-level protagonist is a speechwriter named Arthur Vlaminck (it's confusing, but I think Vlaminck=Baudry=Lanzac) is hired to work for the foreign minister, Alexandre Taillard de Vorms. Vorms is de Villepin, and there are many additional fictional equivalences--Khemed is Iraq, Jeffrey Cole is Colin Powell, etc.

(SelfMadeHero, 2014) by Abel Lanzac and Christophe Blain. This is a rather bizarre book, but I found it captivating. Lanzac is the pen-name of a French diplomat, Antonin Baudry. Baudry worked for the French Foreign Minister, Dominique de Villepin during the run-up to the Iraq War, and France was being hectored by the U.S. to join its "coalition of the willing." France wisely chose not to participate in this foolish war. Now one might expect someone like Baudry to write a memoir of the experience. What no one would expect is that he would fictionalize it in a graphic novel, Quai d'Orsay (retitled Weapon of Mass Diplomacy for English speaking readers). In the book, the low-level protagonist is a speechwriter named Arthur Vlaminck (it's confusing, but I think Vlaminck=Baudry=Lanzac) is hired to work for the foreign minister, Alexandre Taillard de Vorms. Vorms is de Villepin, and there are many additional fictional equivalences--Khemed is Iraq, Jeffrey Cole is Colin Powell, etc.

![]()

Abel Lanzac and Christophe Blain, Weapons of Mass Diplomacy p. 21

Vorms at first seems to be a distracted blowhard, utterly dependent on his staff (especially his deputy, Claude). Cristophe Blain's artwork serves the story well here--Vorms is a hurricane of urgency, shoulders always backed up, gestures always emphatic. It's actually quite clever how it draws you in, thinking that the whole thing is a comedy at the expense of Vorms, as in a sequence where he compares a good political speech to Tintin.

![]()

Abel Lanzac and Christophe Blain, Weapons of Mass Diplomacy p.45, top tier

But as the story progresses, you learn quite a lot about diplomacy as it is practiced at this level. And the story climaxes with a meeting of the U.N. Security Council, taking place after Cole has given his speech "proving" the presence of weapons of mass destruction in Khemed (this is based on an actual speech by Powell to the U.N. which has subsequently been proven to be false in all particulars). Vorms gives a stirring speech explaining why France cannot support a U.N. resolution against Khemed that amounts to giving the U.N. approval to war. Again, this speech was actually given by de Villepin. Obviously the opposition by France (and other countries) did not prevent the Iraq war, but it did prevent the U.N. from backing it. Somehow, this often wacky comic book manages to effectively depict the importance of that moment. I recommend Weapons of Mass Diplomacy highly.

![]()

Showa 1926-1939: A History of Japan![]() and Showa 1939-1944: A History of Japan

and Showa 1939-1944: A History of Japan![]() (Drawn & Quarterly, 2014) by Shigeru Mizuki. Shigeru Mizuki is in legend in Japanese comics, best known for his comics dealing with yōkai, supernatural beings from Japanese folklore. This series of books (two of which have been published in English, with more to come) tell the history of the Showa era, which lasted from 1926 until 1989, during the reign of Emperor Hirohito. Mizuki intersperses his own life story with sections of more-or-less straight history.

(Drawn & Quarterly, 2014) by Shigeru Mizuki. Shigeru Mizuki is in legend in Japanese comics, best known for his comics dealing with yōkai, supernatural beings from Japanese folklore. This series of books (two of which have been published in English, with more to come) tell the history of the Showa era, which lasted from 1926 until 1989, during the reign of Emperor Hirohito. Mizuki intersperses his own life story with sections of more-or-less straight history.

![]()

Shigeru Mizuki, Showa 1926-1939: A History of Japan p 273

The auto-biographical sequences, such as the above where his grandmother dies, are drawn in his typical "cartoony" style. It's a style that feels very personal, very much his own. The historical sections, on the other hand, often rely greatly on photo-reference.

![]()

Shigeru Mizuki, Showa 1939-1944: A History of Japan p 130

The distinction between these two styles separates the two sections and gives the memoir part a more subjective feeling while giving the history part a more objective feeling. But the problem with these books is that the two parts don't really mesh. Obviously Mizuki's life is affected by what is happening in his country, as when he is drafted in 1942. Mizuki would ultimately lose an arm in combat. But most of the time, there is a feeling that life in his small town is more-or-less unaffected by the politics of Japan happening far away in Tokyo.

It would have been better, then, to split Showa into two separate books--one a memoir and one a history. As it is, the two sides of this story of modern Japan are an uncomfortable fit.

I'm still trying to catch up blogging about comics I've read this summer. You can see more reviews here as well as my guide to Jesse Moynihan's Forming. This time around, I'm looking at some comics from Argentina, Belgium, France and Japan. Aside from their shared non-American origins, they don't have anything in common. Or one could say that the only things they have in common are things they lack--there are no superheroes in these books, no fights between good and evil, etc. This doesn't mean that they're good. Your mileage may vary. Mine did.

Macanudo #1

(Enchanted Lion Books, 2014) by Liniers. Liniers is the pen-name for Ricardo Siri, creator of the daily comic strip Macanudo. He and his wife also run a small publishing house called La Editorial Común, which publishes some very high quality Argentine, European and North American alternative comics. His drawing style is excellent, and his strips have great "timing." He often employs "silent" panels to provide a "rest" in the rhythm of the gag. Because are stand-alone strips, the gag is important. Liniers humor is more wry than laugh-out-loud funny. Many of his strips involve taking classic, cliched humor situations and tweaking them (as in the two examples below).

(Enchanted Lion Books, 2014) by Liniers. Liniers is the pen-name for Ricardo Siri, creator of the daily comic strip Macanudo. He and his wife also run a small publishing house called La Editorial Común, which publishes some very high quality Argentine, European and North American alternative comics. His drawing style is excellent, and his strips have great "timing." He often employs "silent" panels to provide a "rest" in the rhythm of the gag. Because are stand-alone strips, the gag is important. Liniers humor is more wry than laugh-out-loud funny. Many of his strips involve taking classic, cliched humor situations and tweaking them (as in the two examples below).

My problem with Linier's comics is that they really aren't all that funny. They're a little funny, sure. I don't hate them--I just don't love them. But I think that a kid, maybe 10 or 11, might find these hilarious the same way I found, say, B.C. hilarious at that age. So perhaps I'm the wrong audience for Macanudo. In any case, one can't deny that it's a very well-crafted comic strip.

White Cube

(Drawn & Quarterly, 2014) by Brecht Vandenbroucke. This seemed right up my alley--comics about art and the art world. The title refers to the classic modernist white cube

(Drawn & Quarterly, 2014) by Brecht Vandenbroucke. This seemed right up my alley--comics about art and the art world. The title refers to the classic modernist white cube gallery (as well as the well-known contemporary art gallery, White Cube). White Cube stars two identical male protagonists who look at art, buy art and make art with absurd results. The style of the art and the humor recalls the classic Belgian comic CowboyHenk by Kamagurka and Herr Seele. But unfortunately, White Cube is far inferior to Cowboy Henk.

gallery (as well as the well-known contemporary art gallery, White Cube). White Cube stars two identical male protagonists who look at art, buy art and make art with absurd results. The style of the art and the humor recalls the classic Belgian comic CowboyHenk by Kamagurka and Herr Seele. But unfortunately, White Cube is far inferior to Cowboy Henk.

Brecht Vandenbrouke, White Cube p. 25

This witless and cruel joke typifies much of what is in the book. It's nasty without being funny. It seems almost unfair to mention it in relation to Cowboy Henk. Here's a Cowboy Henk strip for comparison.

(from Smoke Signal, Desert Island's in-house comics tabloid.)

Only one Cowboy Henk book has been published in English,Cowboy Henk: King of Dental Floss, and that was way back in 1994. Yes to Kamagurka and Herr Seele; no to Brecht Vandenbroucke!

Weapons of Mass Diplomacy

(SelfMadeHero, 2014) by Abel Lanzac and Christophe Blain. This is a rather bizarre book, but I found it captivating. Lanzac is the pen-name of a French diplomat, Antonin Baudry. Baudry worked for the French Foreign Minister, Dominique de Villepin during the run-up to the Iraq War, and France was being hectored by the U.S. to join its "coalition of the willing." France wisely chose not to participate in this foolish war. Now one might expect someone like Baudry to write a memoir of the experience. What no one would expect is that he would fictionalize it in a graphic novel, Quai d'Orsay (retitled Weapon of Mass Diplomacy for English speaking readers). In the book, the low-level protagonist is a speechwriter named Arthur Vlaminck (it's confusing, but I think Vlaminck=Baudry=Lanzac) is hired to work for the foreign minister, Alexandre Taillard de Vorms. Vorms is de Villepin, and there are many additional fictional equivalences--Khemed is Iraq, Jeffrey Cole is Colin Powell, etc.

(SelfMadeHero, 2014) by Abel Lanzac and Christophe Blain. This is a rather bizarre book, but I found it captivating. Lanzac is the pen-name of a French diplomat, Antonin Baudry. Baudry worked for the French Foreign Minister, Dominique de Villepin during the run-up to the Iraq War, and France was being hectored by the U.S. to join its "coalition of the willing." France wisely chose not to participate in this foolish war. Now one might expect someone like Baudry to write a memoir of the experience. What no one would expect is that he would fictionalize it in a graphic novel, Quai d'Orsay (retitled Weapon of Mass Diplomacy for English speaking readers). In the book, the low-level protagonist is a speechwriter named Arthur Vlaminck (it's confusing, but I think Vlaminck=Baudry=Lanzac) is hired to work for the foreign minister, Alexandre Taillard de Vorms. Vorms is de Villepin, and there are many additional fictional equivalences--Khemed is Iraq, Jeffrey Cole is Colin Powell, etc.

Abel Lanzac and Christophe Blain, Weapons of Mass Diplomacy p. 21

Vorms at first seems to be a distracted blowhard, utterly dependent on his staff (especially his deputy, Claude). Cristophe Blain's artwork serves the story well here--Vorms is a hurricane of urgency, shoulders always backed up, gestures always emphatic. It's actually quite clever how it draws you in, thinking that the whole thing is a comedy at the expense of Vorms, as in a sequence where he compares a good political speech to Tintin.

Abel Lanzac and Christophe Blain, Weapons of Mass Diplomacy p.45, top tier

But as the story progresses, you learn quite a lot about diplomacy as it is practiced at this level. And the story climaxes with a meeting of the U.N. Security Council, taking place after Cole has given his speech "proving" the presence of weapons of mass destruction in Khemed (this is based on an actual speech by Powell to the U.N. which has subsequently been proven to be false in all particulars). Vorms gives a stirring speech explaining why France cannot support a U.N. resolution against Khemed that amounts to giving the U.N. approval to war. Again, this speech was actually given by de Villepin. Obviously the opposition by France (and other countries) did not prevent the Iraq war, but it did prevent the U.N. from backing it. Somehow, this often wacky comic book manages to effectively depict the importance of that moment. I recommend Weapons of Mass Diplomacy highly.

Showa 1926-1939: A History of Japan

and Showa 1939-1944: A History of Japan

and Showa 1939-1944: A History of Japan (Drawn & Quarterly, 2014) by Shigeru Mizuki. Shigeru Mizuki is in legend in Japanese comics, best known for his comics dealing with yōkai, supernatural beings from Japanese folklore. This series of books (two of which have been published in English, with more to come) tell the history of the Showa era, which lasted from 1926 until 1989, during the reign of Emperor Hirohito. Mizuki intersperses his own life story with sections of more-or-less straight history.

(Drawn & Quarterly, 2014) by Shigeru Mizuki. Shigeru Mizuki is in legend in Japanese comics, best known for his comics dealing with yōkai, supernatural beings from Japanese folklore. This series of books (two of which have been published in English, with more to come) tell the history of the Showa era, which lasted from 1926 until 1989, during the reign of Emperor Hirohito. Mizuki intersperses his own life story with sections of more-or-less straight history.

Shigeru Mizuki, Showa 1926-1939: A History of Japan p 273

The auto-biographical sequences, such as the above where his grandmother dies, are drawn in his typical "cartoony" style. It's a style that feels very personal, very much his own. The historical sections, on the other hand, often rely greatly on photo-reference.

Shigeru Mizuki, Showa 1939-1944: A History of Japan p 130

The distinction between these two styles separates the two sections and gives the memoir part a more subjective feeling while giving the history part a more objective feeling. But the problem with these books is that the two parts don't really mesh. Obviously Mizuki's life is affected by what is happening in his country, as when he is drafted in 1942. Mizuki would ultimately lose an arm in combat. But most of the time, there is a feeling that life in his small town is more-or-less unaffected by the politics of Japan happening far away in Tokyo.

It would have been better, then, to split Showa into two separate books--one a memoir and one a history. As it is, the two sides of this story of modern Japan are an uncomfortable fit.

or

or  , Brown skipped serialization and published it as a complete whole--this has become pretty typical for art comics. The age of the "comic book" is pretty much over for art comics.

, Brown skipped serialization and published it as a complete whole--this has become pretty typical for art comics. The age of the "comic book" is pretty much over for art comics. .

.

that was meant to "mystify rather than clarify."

that was meant to "mystify rather than clarify."

and

and  I've loved her work since I first read her DTWOF collections. As I sit here typing this, I can look at the wall opposite me and see a piece of Alison Bechdel art--one of her DTWOF strips entitled "Boy Trouble."

I've loved her work since I first read her DTWOF collections. As I sit here typing this, I can look at the wall opposite me and see a piece of Alison Bechdel art--one of her DTWOF strips entitled "Boy Trouble."

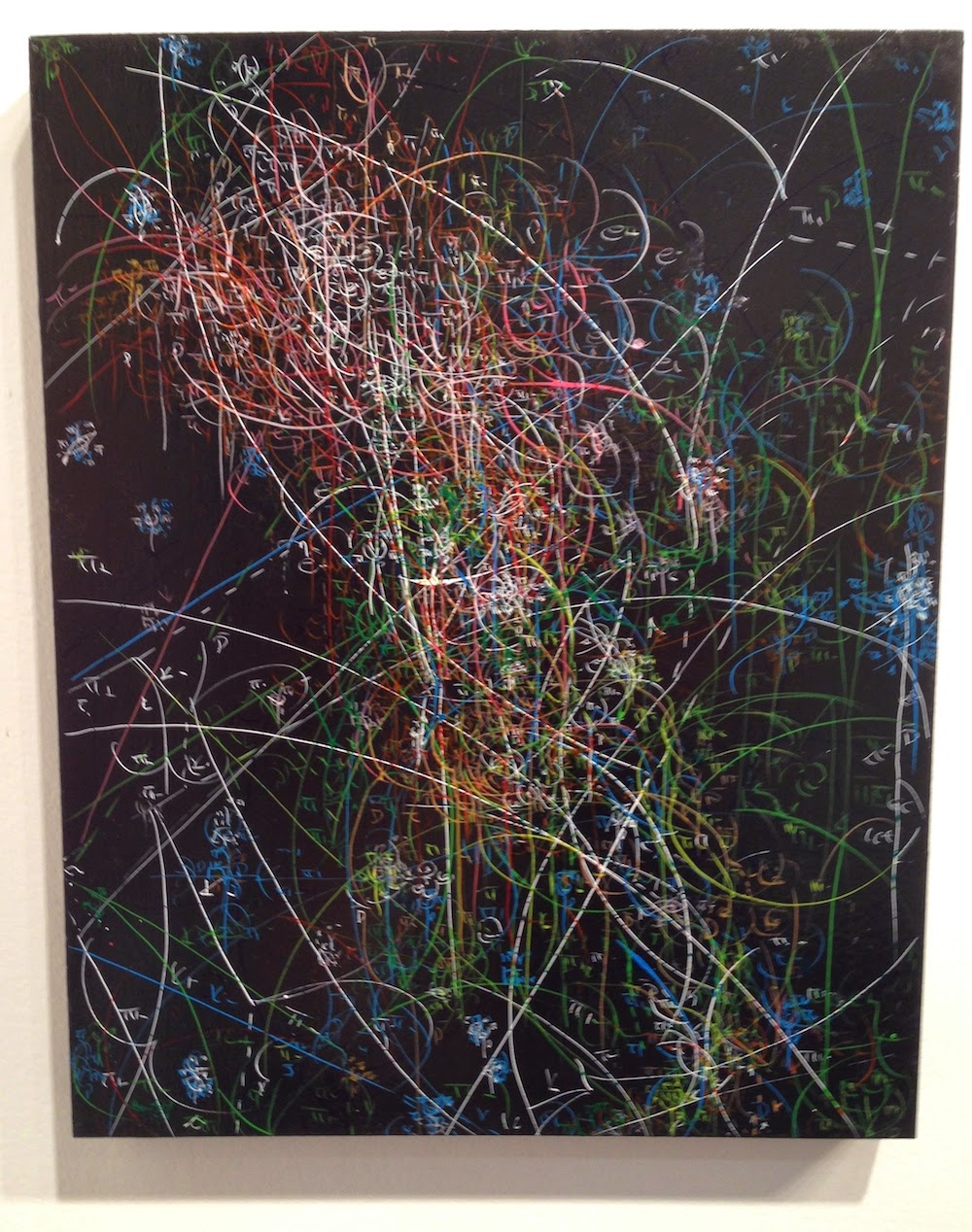

, from which I learned about the four colors the dead person sees in the Bardo state between death and rebirth. Those colors float through my painting. When my father was dying I urged him to focus his consciousness on the radiant white light described in the book.

, from which I learned about the four colors the dead person sees in the Bardo state between death and rebirth. Those colors float through my painting. When my father was dying I urged him to focus his consciousness on the radiant white light described in the book.

(2004) by

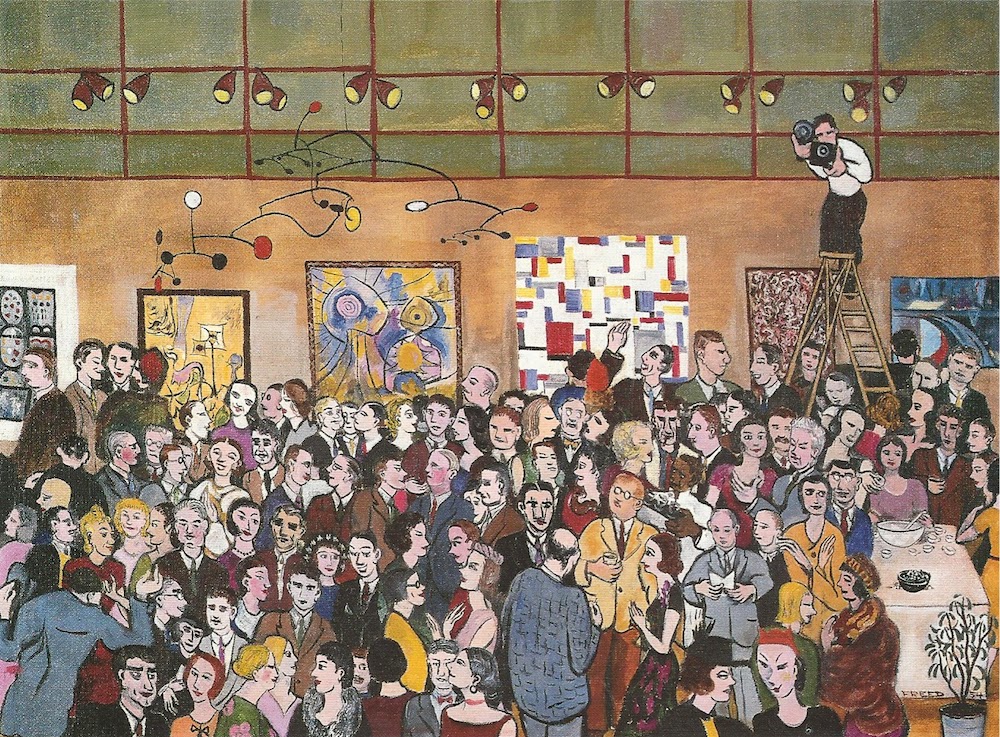

(2004) by  , a 1982 exhibit at the Corcoran Gallery, and the market for his work expanded accordingly. If he had started using Winsor Newton paints and doing his work on stretched and primed canvas, would it have lost "authenticity"?

, a 1982 exhibit at the Corcoran Gallery, and the market for his work expanded accordingly. If he had started using Winsor Newton paints and doing his work on stretched and primed canvas, would it have lost "authenticity"?

by

by

(Cyrus identifies Rozanov as a nihilist, but most references I've seen paint him as a highly eccentric conservative intellectual). The phrase was quoted in a Situationist polemic from 1967, and repeated in Greil Marcus's

(Cyrus identifies Rozanov as a nihilist, but most references I've seen paint him as a highly eccentric conservative intellectual). The phrase was quoted in a Situationist polemic from 1967, and repeated in Greil Marcus's  .

.