Robert Boyd

During FotoFest, I find myself getting photo-ed out. I like photography fine, but so much of it feels similar--here are some interesting images, well composed, arresting, beautiful or disturbing or thoughtful, of some intriguing or important subject matter. And here are some more. You get tired of images during FotoFest. It makes me want to put on headphones and close my eyes after a while.

So I wasn't expecting much when I went to the Mission to check out their FotoFest shows. At least it was a group show, which guaranteed variety. But my favorite thing happened--I walked in having no great expectations and walked out really pleased by what I had seen.

![]()

Bryan Zanisnik, 18 Years of American Dreams, 2010, photograph, 60 x 83 inches

The Mission is hosting a group show called Lateral featuring 10 photographers. Bryan Zanisnik had a room to himself, creating a small solo exhibit within the larger group exhibit. Zanisnik created fairly elaborate tableaux in rooms that he either constructed or which already had an unfinished look (for example, an attic space). In this way, the work reminded me of some of Nic Nicosia's photos of constructed rooms, but Zanisnik's images are much more cluttered and visually busy.

![]()

Bryan Zanisnik, 22 Monoliths and a Rolodex, 2011, photograph, 42 49 inches

Part of that visual clutter is from what he puts the rooms he shoots, but a big part is the way he papers the walls. 18 Years of American Dreams has a wall covered with baseball cards. The baseball card motif continues in 22 Monoliths and a Rolodex, where the stuff pinned to the walls are pieces of paper (they look like printed out emails) onto which is stenciled a prose narrative about selling baseball cards to a collector.

Collections and attics and basements--it suggests the kind of person who gets involved in collecting something and storing it in underused places in one's home, until something makes the collector sell. It's a common enough obsession--I'm certainly that kind of person, and I've known many like myself in my life. The density of these images makes me think of the environments that collectors develop for their collections. A living collection is always one step ahead of anyone's ability to seriously organize it; we collectors are simply socially acceptable hoarders, if we're honest about it.

![]()

Jeremy Bolen, Bioluminescent Communications (in Mosquito Bay), 2011, archival pigment print on Hahnemuhle paper, 44 x 34 inches

Jeremy Bolen's work in the show belongs to a classic genre, nature photography. But their all-over composition suggests something different. When I first saw them, I thought of blurry stars or maybe the flashes of light from sub-atomic particle reactions in a cloud chamber. If fact, they are photos of bioluminescent organisms taken under water. To me, the fact that I could mistake this image for something very small (charged particles) or very large (stars) when it is actually something alive suggests a thing that repeats throughout the universe. If I weren't so suspicious of the term, I might use the word "sublime" to describe what I was seeing.

![]()

Jeremy Bolen, Bioluminescent Communications (in Mosquito Bay) #4, 2011, archival pigment print on Hahnemuhle paper, 44 x 34 inches

![]()

Erica Bohm, Astro II, 2010-2011, digital photograph mounted on plexiglas, 24 x 20 inches

Erica Bohm's photos are intriguing in part because they include images that she couldn't have taken--Buzz Aldrin's footprint on the moon, for example. My assumption is that she took these photos at NASA, either photographing other photographs or exhibits of actual space hardware. But what she does with the photos gives them a majestic and somewhat mysterious look. Astro II is positively ghostly. Given the danger involved with being an astronaut and the high number of deaths in the profession, this haunted photo feels appropriate.

![]()

Jeroen Nelemans, The more I see the less I grasp #GR386300, 2011, lightbox, 25.8 x 25.8 inches

The more I see the less I grasp is a series by Jeroen Nelemans of lightbox photos seen from the back. The photo image is a somewhat generic "majestic nature" image, but what makes it interesting is the literal foregrounding of the fluorescent lights. I can't explain why (which makes me a pretty inadequate critic, I guess), but for me, the image was somehow made more beautiful seen like this. It may be partly the defamiliarization effect of seeing the mechanism normally behind the lightbox, but that seems too facile an explanation. I think the light itself shining back onto the image is beautiful. Certainly Dan Flavin found this kind of light beautiful; he was careful to not combine it with anything--just lights and walls. But why not combine it with other images? In any case, it seems to work here.

I was also impressed with the work of John Opera, Daniel Shea and Marcelo Grossman. There was a lot in Lateral to like. It runs through May 15 at The Mission.

During FotoFest, I find myself getting photo-ed out. I like photography fine, but so much of it feels similar--here are some interesting images, well composed, arresting, beautiful or disturbing or thoughtful, of some intriguing or important subject matter. And here are some more. You get tired of images during FotoFest. It makes me want to put on headphones and close my eyes after a while.

So I wasn't expecting much when I went to the Mission to check out their FotoFest shows. At least it was a group show, which guaranteed variety. But my favorite thing happened--I walked in having no great expectations and walked out really pleased by what I had seen.

Bryan Zanisnik, 18 Years of American Dreams, 2010, photograph, 60 x 83 inches

The Mission is hosting a group show called Lateral featuring 10 photographers. Bryan Zanisnik had a room to himself, creating a small solo exhibit within the larger group exhibit. Zanisnik created fairly elaborate tableaux in rooms that he either constructed or which already had an unfinished look (for example, an attic space). In this way, the work reminded me of some of Nic Nicosia's photos of constructed rooms, but Zanisnik's images are much more cluttered and visually busy.

Bryan Zanisnik, 22 Monoliths and a Rolodex, 2011, photograph, 42 49 inches

Part of that visual clutter is from what he puts the rooms he shoots, but a big part is the way he papers the walls. 18 Years of American Dreams has a wall covered with baseball cards. The baseball card motif continues in 22 Monoliths and a Rolodex, where the stuff pinned to the walls are pieces of paper (they look like printed out emails) onto which is stenciled a prose narrative about selling baseball cards to a collector.

Collections and attics and basements--it suggests the kind of person who gets involved in collecting something and storing it in underused places in one's home, until something makes the collector sell. It's a common enough obsession--I'm certainly that kind of person, and I've known many like myself in my life. The density of these images makes me think of the environments that collectors develop for their collections. A living collection is always one step ahead of anyone's ability to seriously organize it; we collectors are simply socially acceptable hoarders, if we're honest about it.

Jeremy Bolen, Bioluminescent Communications (in Mosquito Bay), 2011, archival pigment print on Hahnemuhle paper, 44 x 34 inches

Jeremy Bolen's work in the show belongs to a classic genre, nature photography. But their all-over composition suggests something different. When I first saw them, I thought of blurry stars or maybe the flashes of light from sub-atomic particle reactions in a cloud chamber. If fact, they are photos of bioluminescent organisms taken under water. To me, the fact that I could mistake this image for something very small (charged particles) or very large (stars) when it is actually something alive suggests a thing that repeats throughout the universe. If I weren't so suspicious of the term, I might use the word "sublime" to describe what I was seeing.

Jeremy Bolen, Bioluminescent Communications (in Mosquito Bay) #4, 2011, archival pigment print on Hahnemuhle paper, 44 x 34 inches

Erica Bohm, Astro II, 2010-2011, digital photograph mounted on plexiglas, 24 x 20 inches

Erica Bohm's photos are intriguing in part because they include images that she couldn't have taken--Buzz Aldrin's footprint on the moon, for example. My assumption is that she took these photos at NASA, either photographing other photographs or exhibits of actual space hardware. But what she does with the photos gives them a majestic and somewhat mysterious look. Astro II is positively ghostly. Given the danger involved with being an astronaut and the high number of deaths in the profession, this haunted photo feels appropriate.

Jeroen Nelemans, The more I see the less I grasp #GR386300, 2011, lightbox, 25.8 x 25.8 inches

The more I see the less I grasp is a series by Jeroen Nelemans of lightbox photos seen from the back. The photo image is a somewhat generic "majestic nature" image, but what makes it interesting is the literal foregrounding of the fluorescent lights. I can't explain why (which makes me a pretty inadequate critic, I guess), but for me, the image was somehow made more beautiful seen like this. It may be partly the defamiliarization effect of seeing the mechanism normally behind the lightbox, but that seems too facile an explanation. I think the light itself shining back onto the image is beautiful. Certainly Dan Flavin found this kind of light beautiful; he was careful to not combine it with anything--just lights and walls. But why not combine it with other images? In any case, it seems to work here.

I was also impressed with the work of John Opera, Daniel Shea and Marcelo Grossman. There was a lot in Lateral to like. It runs through May 15 at The Mission.

, p. 6, 1993). So when someone makes an argument that we are excluding a certain class of art for reasons of "quality," I am suspicious.

, p. 6, 1993). So when someone makes an argument that we are excluding a certain class of art for reasons of "quality," I am suspicious.

by Mauricio Lasansky and the drawings were phenomenal. I had never seen that before, that level of skill, with a profoundly serious topic, the holocaust, shocking rape scenes, it was enormously impactful, so I found Lasansky at the University of Iowa, and actually went there for graduate work because of him. I don’t think I knew where Iowa was, or the difference between Iowa and Ohio, well Iowa’s on the plains and it’s freezing cold, but I experienced his drawing first hand, not a lot of other stuff has inspired me, except film, newspaper, people’s behavior.

by Mauricio Lasansky and the drawings were phenomenal. I had never seen that before, that level of skill, with a profoundly serious topic, the holocaust, shocking rape scenes, it was enormously impactful, so I found Lasansky at the University of Iowa, and actually went there for graduate work because of him. I don’t think I knew where Iowa was, or the difference between Iowa and Ohio, well Iowa’s on the plains and it’s freezing cold, but I experienced his drawing first hand, not a lot of other stuff has inspired me, except film, newspaper, people’s behavior.

. Many of his comics are drawn in silhouette form (such as

. Many of his comics are drawn in silhouette form (such as

, is the perfect art fair artwork. It takes something cheap and mass-produced (but wonderful for the ideas it contains) and turns it into a valuable unique artwork for a member of the "leisure class" to buy--without any implied obligation that said leisure class member needs to read the words the original contained!

, is the perfect art fair artwork. It takes something cheap and mass-produced (but wonderful for the ideas it contains) and turns it into a valuable unique artwork for a member of the "leisure class" to buy--without any implied obligation that said leisure class member needs to read the words the original contained!

. I wonder if by portraying him in blackface, John Hancock is suggesting that freakshows were to people with disabilities what minstrelsy was to African-Americans. Or maybe he was just being provocative.

. I wonder if by portraying him in blackface, John Hancock is suggesting that freakshows were to people with disabilities what minstrelsy was to African-Americans. Or maybe he was just being provocative.

.

.

. My Saint Rose of Lima sculpture is in the collection of the museum in Lima. Love that city!

. My Saint Rose of Lima sculpture is in the collection of the museum in Lima. Love that city!

, an anthology of writing from the great Chicago-based art magazine, and a passage by Derek Guthrie, one of the co-founders with Jane Allen, resonated for me. Allen and Guthrie had been critics at the Chicago Tribune when they were suddenly fired, apparently for writing an article about the Illinois Arts Council that made the wrong people mad. He blamed the Chicago "collector/dealer/trustee" cabal. He writes:

, an anthology of writing from the great Chicago-based art magazine, and a passage by Derek Guthrie, one of the co-founders with Jane Allen, resonated for me. Allen and Guthrie had been critics at the Chicago Tribune when they were suddenly fired, apparently for writing an article about the Illinois Arts Council that made the wrong people mad. He blamed the Chicago "collector/dealer/trustee" cabal. He writes:

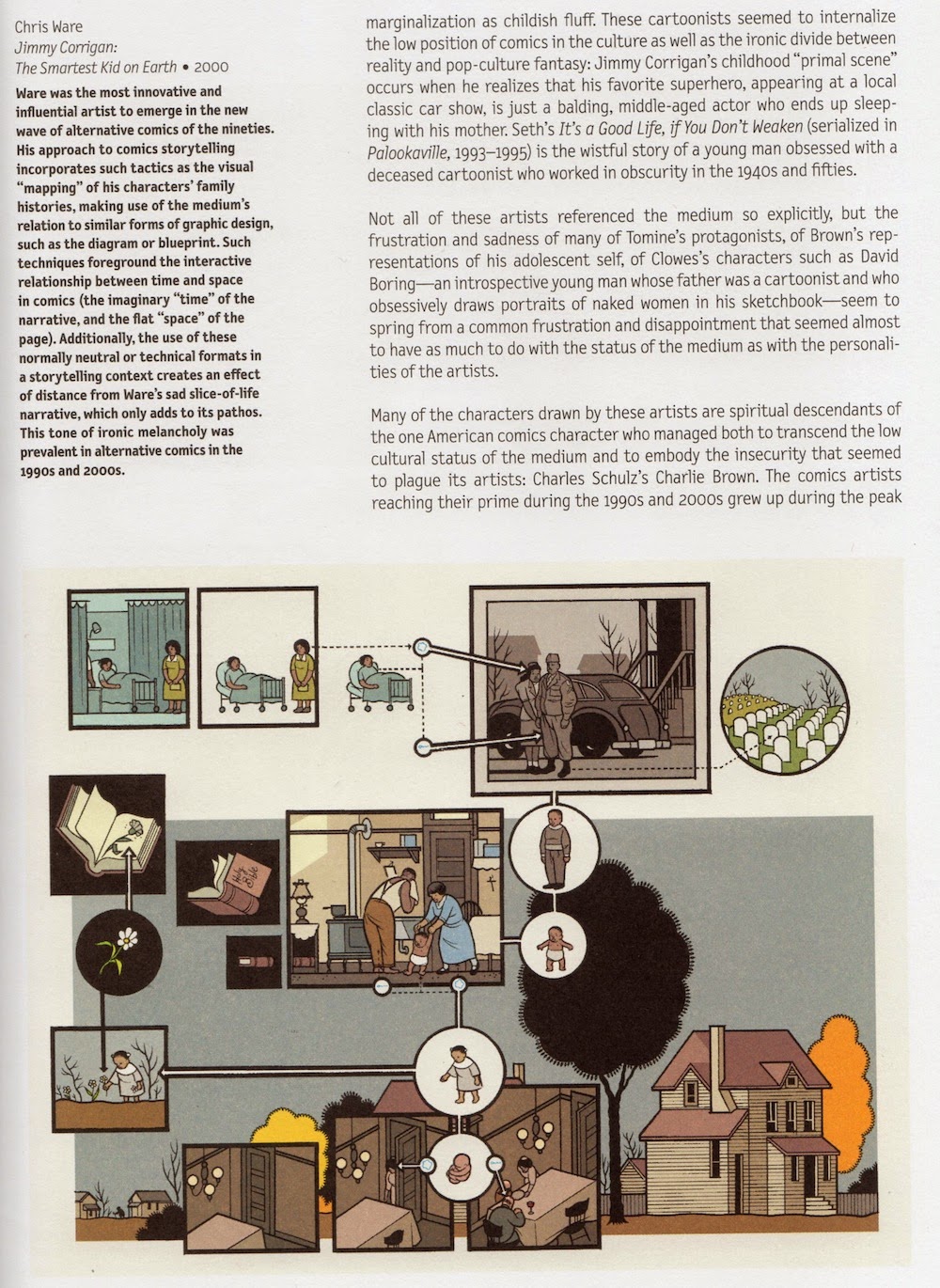

comes close, but its text is pretty skimpy. (Not that I'm complaining--I rate this book as the single best volume of comics ever published.)

comes close, but its text is pretty skimpy. (Not that I'm complaining--I rate this book as the single best volume of comics ever published.) (two art history survey texts that were popular when I was an undergrad)? Two candidates have been recently published.

(two art history survey texts that were popular when I was an undergrad)? Two candidates have been recently published.  by Thierry Smolderen (translated by Bart Beatty and Nick Nguyen) covers the very early history of comics, while

by Thierry Smolderen (translated by Bart Beatty and Nick Nguyen) covers the very early history of comics, while

. Smolderen places this work within the world of theater (Topffer was an avid amateur actor). Smolderen relates Töppfer's use of sequential gestures in his picture novels to the theories of acting and pantomime that were common at the time. For a visual artist like Töppfer, various theories of theater--among others, Smolderen specifically references Gotthold Ephraim Lessing's Laocoon, which theorized in favor of a poetry of progressive actions as opposed to descriptive poetry--spoke to a way out of detailed, realistic academic images and into sequential storytelling with images.

. Smolderen places this work within the world of theater (Topffer was an avid amateur actor). Smolderen relates Töppfer's use of sequential gestures in his picture novels to the theories of acting and pantomime that were common at the time. For a visual artist like Töppfer, various theories of theater--among others, Smolderen specifically references Gotthold Ephraim Lessing's Laocoon, which theorized in favor of a poetry of progressive actions as opposed to descriptive poetry--spoke to a way out of detailed, realistic academic images and into sequential storytelling with images.

by Paul Gravett). As for histories of comics, they're too numerous to mention. But they differ from Global History in concentrating on personalities, business history and the culture of the comics world(s). Global History can't help but touch on some of that, but its focus is on the works within the context of history.

by Paul Gravett). As for histories of comics, they're too numerous to mention. But they differ from Global History in concentrating on personalities, business history and the culture of the comics world(s). Global History can't help but touch on some of that, but its focus is on the works within the context of history.

, dealing with the relationship between the world of comics and the comics world, is required reading if you want to think about these two things together. But it's not the last word since comics and art keep on going. For instance, this month

, dealing with the relationship between the world of comics and the comics world, is required reading if you want to think about these two things together. But it's not the last word since comics and art keep on going. For instance, this month

, Ben Davis said that the difference between fine artists and commercial artists is that fine artists are essentially bourgeois while commercial artists were working class. This has nothing to do with their respective incomes or wealth, but with their autonomy as creative people. If you agree with Davis's formulation, then score one for the working class!

, Ben Davis said that the difference between fine artists and commercial artists is that fine artists are essentially bourgeois while commercial artists were working class. This has nothing to do with their respective incomes or wealth, but with their autonomy as creative people. If you agree with Davis's formulation, then score one for the working class!