Robert Boyd

Kind of a lot of stuff happening this weekend. When was the last time Lawndale and the Art League had an opening on the same night? I guess with Thanksgiving next week, a lot of events have to be crammed into this week. Good times!

THURSDAY

![]()

Sally Bennet, Making Faces, 32x31x2.5 inches

Sally Bennett and Ann Huey: New Works at Koelsch Gallery, 6–8 pm. Work that plays with illustration and design.

![]()

David Row, Ellipsis, 2012, Oil on canvas, 50 x 96 inches

David Row: Elements at McClain Gallery, 6:30–8:30 pm. Paintings, works on paper and sculptures made of cast glass.

FRIDAY

![]()

from Emily Peacock's W.T. series

Learning Curve 7 and See Food: Contemporary Photography and the Ways We Eat curated by Natalie Zelt and featuring Corey Arnold (Portland, OR), Jonathan Blaustein (Arroyo Hondo, NM), Christin Boggs (Washington, D.C.), Damaris Booth (London, England), Nolan Calisch (Portland, OR), Jody Horton (Austin, TX), Andrzej Maciejewski (Ontario, Canada), Mark Menjivar (San Antonio, TX), Emily Peacock (Houston, TX), Emily Sloan (Houston, TX) and David Welch (Martha's Vineyard, MA) at the Houston Center for Photography, 6–8 pm (with a panel discussion for See Food Saturday from noon to 1 pm).Learning Curve 7 is their annual student show, and See Food is pictures of food, obviously.

![]()

That's Monica Vidal, looking pretty damn ecstatic in front of her installation Falling Hive

FALLING: Monica Vidal and Everyday Grace: Sedrick Huckaby at Art League Houston 6–9 pm, with artists' talks at 6:30 pm for Sedrick Huckaby and 7 pm for Monica Vidal. Monica Vidal brings Falling Hive home to Houston, just down the hall from Sedrick Huckaby's paintings.

![]()

Beth Secor, Sudden Appearance in Places Unknown, 2013, Found embroidered linens with drawing and embroidery, 30" x 30"

Superficial Outgrowths by Sang-Mi Yoo, Melinda Laszczynski and Jessica Ninci: This End Up, Beth Secor: The Significance of "Material" and Regina Agu: Nerve Endings at Lawndale Art Center, 6:30–8:30 pm. I don't have much to say except that all these shows look great!

FRIDAY THROUGH SUNDAY

![]()

Winter Street Studios

8th Annual Winter Holiday Art Market at Winter Street, 6 to 8 pm Friday ($10 admission), 11 am to 8 pm Saturday (free) and 11 am to 4 pm Sunday (free). Don't let the bleak industrial landscape above fool you--this weekend it will be packed with artists and craftsmen selling their stuff.

SATURDAY

![]()

They played at last years' ArtCrawl

ArtCrawl at multiple locations just north of Downtown and on the East End, 10 am to 9 pm. The annual trip through various art spaces and artists' studios near downtown. ArtCrawl related events include:

![]()

Anasheh Partiai

The Art of Everyday Politics featuring Amber Baker, Anasheh Partiai, Sarah Rodriguez, and Brandon Zech at Alabama Song, 8 pm Saturday to 8 pm Sunday. Hey, if you have 24 hours free, there's a one day (literally) only show with performances by Amber Baker at 6:45, Anasheh Partiai at 7 pm and Brandon Zech at 7:15, plus other activities throughout the night to help you stay awake!

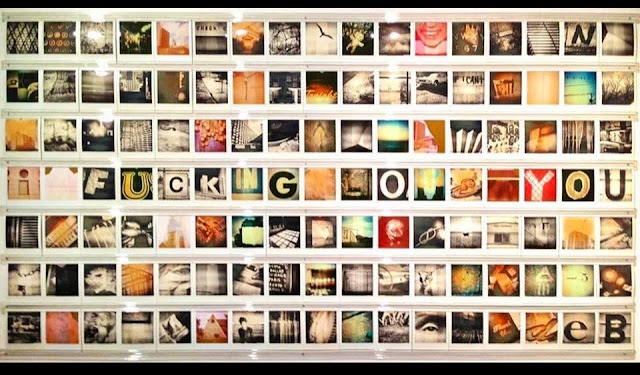

![]()

Debora Smail, I fucking love you, Polaroid Installation

RATIO featuring Jenn Blackburn, Ben Tecumseh DeSoto, David Salinas, JoAnn Santangelo, Alex Larsen, Ashleigh MacLean, Abrahan Garza, Edna Sandoval, Galina Kurlat, Ben Parks, Theresa Escobedo, Emily Peacock, Bryan Forrester, Matthew Landry, Rosa Gurrero, Shannon Duncan, Laura Corley Burlton, Maureen Penders, Mark Audacity Romberg, Traci Matlock, Debora Smail, Joe Winsto and Gary Griffin at El Rincón Social, 7 pm to 2 am. El Rincón Social always have these events that last until 2 am, and old guy that I am, I always wonder who is going to hang out until 2 am? Pathetic, huh? This looks great--a lot of my favorite local photographers will be there.

![Share]()

Kind of a lot of stuff happening this weekend. When was the last time Lawndale and the Art League had an opening on the same night? I guess with Thanksgiving next week, a lot of events have to be crammed into this week. Good times!

THURSDAY

Sally Bennet, Making Faces, 32x31x2.5 inches

Sally Bennett and Ann Huey: New Works at Koelsch Gallery, 6–8 pm. Work that plays with illustration and design.

David Row, Ellipsis, 2012, Oil on canvas, 50 x 96 inches

David Row: Elements at McClain Gallery, 6:30–8:30 pm. Paintings, works on paper and sculptures made of cast glass.

FRIDAY

from Emily Peacock's W.T. series

Learning Curve 7 and See Food: Contemporary Photography and the Ways We Eat curated by Natalie Zelt and featuring Corey Arnold (Portland, OR), Jonathan Blaustein (Arroyo Hondo, NM), Christin Boggs (Washington, D.C.), Damaris Booth (London, England), Nolan Calisch (Portland, OR), Jody Horton (Austin, TX), Andrzej Maciejewski (Ontario, Canada), Mark Menjivar (San Antonio, TX), Emily Peacock (Houston, TX), Emily Sloan (Houston, TX) and David Welch (Martha's Vineyard, MA) at the Houston Center for Photography, 6–8 pm (with a panel discussion for See Food Saturday from noon to 1 pm).Learning Curve 7 is their annual student show, and See Food is pictures of food, obviously.

That's Monica Vidal, looking pretty damn ecstatic in front of her installation Falling Hive

FALLING: Monica Vidal and Everyday Grace: Sedrick Huckaby at Art League Houston 6–9 pm, with artists' talks at 6:30 pm for Sedrick Huckaby and 7 pm for Monica Vidal. Monica Vidal brings Falling Hive home to Houston, just down the hall from Sedrick Huckaby's paintings.

Beth Secor, Sudden Appearance in Places Unknown, 2013, Found embroidered linens with drawing and embroidery, 30" x 30"

Superficial Outgrowths by Sang-Mi Yoo, Melinda Laszczynski and Jessica Ninci: This End Up, Beth Secor: The Significance of "Material" and Regina Agu: Nerve Endings at Lawndale Art Center, 6:30–8:30 pm. I don't have much to say except that all these shows look great!

FRIDAY THROUGH SUNDAY

Winter Street Studios

8th Annual Winter Holiday Art Market at Winter Street, 6 to 8 pm Friday ($10 admission), 11 am to 8 pm Saturday (free) and 11 am to 4 pm Sunday (free). Don't let the bleak industrial landscape above fool you--this weekend it will be packed with artists and craftsmen selling their stuff.

SATURDAY

They played at last years' ArtCrawl

ArtCrawl at multiple locations just north of Downtown and on the East End, 10 am to 9 pm. The annual trip through various art spaces and artists' studios near downtown. ArtCrawl related events include:

- Fotofest Bike Scramble, 11 am to 3:30 pm, starting from FotoFest headquarters.

- ArtCrawl "The Happening" featuring art by Michael Meazell, Alfredo Scaroina, Patrick Renner, Felipe Lopez and Lester Marks, 4 pm until whenevah at David Greave Art Studio.

- RATIO at El Rincón Social (see below for more info)

Anasheh Partiai

The Art of Everyday Politics featuring Amber Baker, Anasheh Partiai, Sarah Rodriguez, and Brandon Zech at Alabama Song, 8 pm Saturday to 8 pm Sunday. Hey, if you have 24 hours free, there's a one day (literally) only show with performances by Amber Baker at 6:45, Anasheh Partiai at 7 pm and Brandon Zech at 7:15, plus other activities throughout the night to help you stay awake!

Debora Smail, I fucking love you, Polaroid Installation

RATIO featuring Jenn Blackburn, Ben Tecumseh DeSoto, David Salinas, JoAnn Santangelo, Alex Larsen, Ashleigh MacLean, Abrahan Garza, Edna Sandoval, Galina Kurlat, Ben Parks, Theresa Escobedo, Emily Peacock, Bryan Forrester, Matthew Landry, Rosa Gurrero, Shannon Duncan, Laura Corley Burlton, Maureen Penders, Mark Audacity Romberg, Traci Matlock, Debora Smail, Joe Winsto and Gary Griffin at El Rincón Social, 7 pm to 2 am. El Rincón Social always have these events that last until 2 am, and old guy that I am, I always wonder who is going to hang out until 2 am? Pathetic, huh? This looks great--a lot of my favorite local photographers will be there.

(1989).

(1989). in 1980. In enumerating the term, he was in effect making an argument against the sole interpretation of photography as a set of linguistic, political, and societal codes. While a photograph naturally contains these codes, of course, Barthes argued that there is an additional kind of meaning inherently embedded in the work. It’s a meaning that defies terminology or code breaking—it is the kind of resonance that connects with the viewer on an intensely emotional level, thereby making the work indescribably unique.

in 1980. In enumerating the term, he was in effect making an argument against the sole interpretation of photography as a set of linguistic, political, and societal codes. While a photograph naturally contains these codes, of course, Barthes argued that there is an additional kind of meaning inherently embedded in the work. It’s a meaning that defies terminology or code breaking—it is the kind of resonance that connects with the viewer on an intensely emotional level, thereby making the work indescribably unique.

, Robert Kushner looks at Michener's collection in terms of a year by year "batting average"--significant works as a percentage of the whole. He calculates Michener's lifetime average at .319, which I'd say is pretty great. Is it crass that I'd like to know what the average is for the Vogels?)

, Robert Kushner looks at Michener's collection in terms of a year by year "batting average"--significant works as a percentage of the whole. He calculates Michener's lifetime average at .319, which I'd say is pretty great. Is it crass that I'd like to know what the average is for the Vogels?)

by Chuck Smith (powerHouse Books)

by Chuck Smith (powerHouse Books)

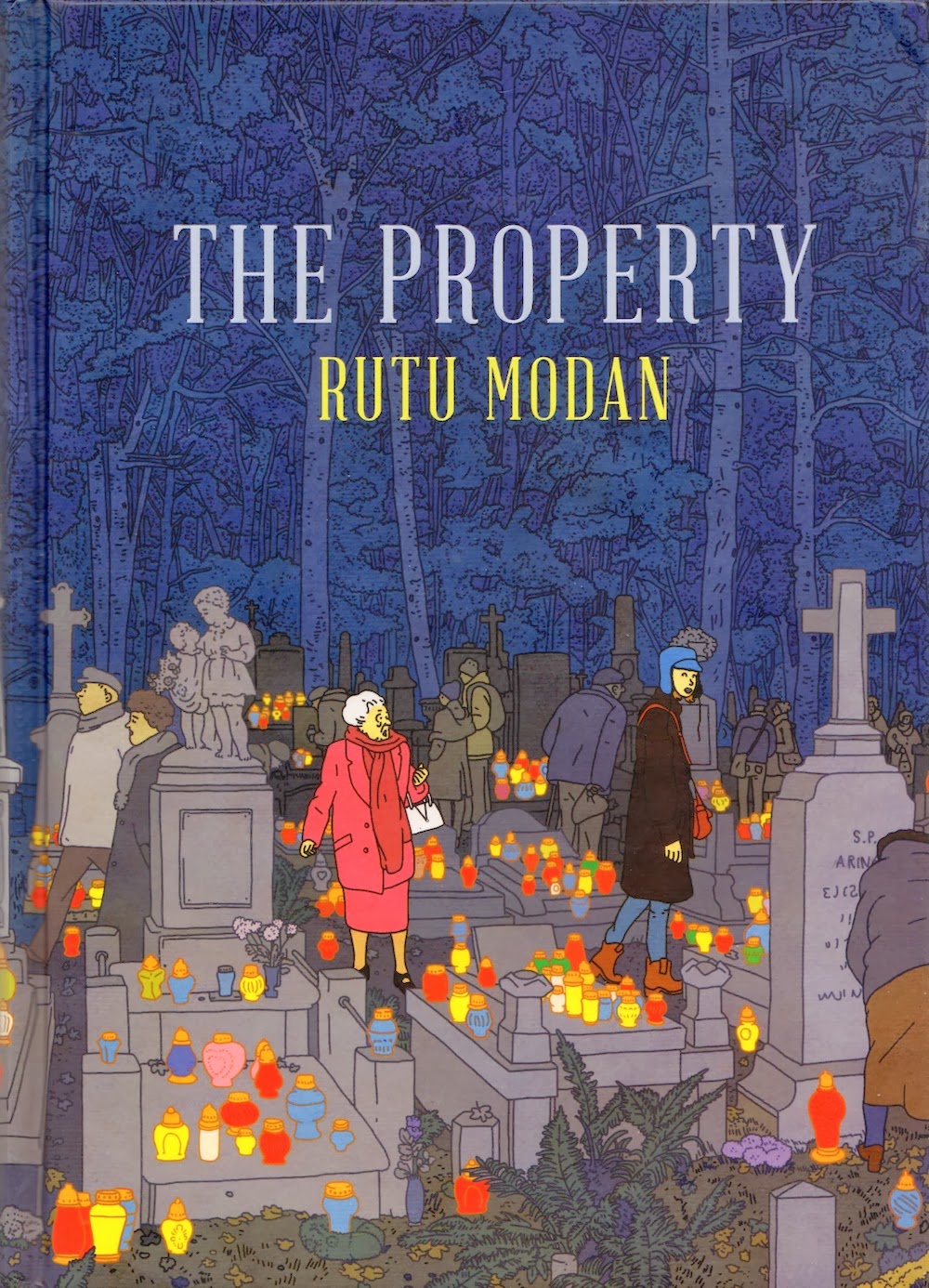

by Rutu Modan (Drawn & Quarterly)

by Rutu Modan (Drawn & Quarterly) by Tony Judt for a grimmer recitation of this distressing history.) The opening and closing scenes on the airplane (coming to Poland and returning to Israel demonstrate the duality between frivolity and seriousness that typifies the story. Of course, it helps that the art is beautiful and the visual storytelling lively. It's Modan's best comic from a career of excellent work, and it suggests where she can go in the future. My main worry now is that she may end up seduced away from comics to film--Modan would be a great screenwriter/director.

by Tony Judt for a grimmer recitation of this distressing history.) The opening and closing scenes on the airplane (coming to Poland and returning to Israel demonstrate the duality between frivolity and seriousness that typifies the story. Of course, it helps that the art is beautiful and the visual storytelling lively. It's Modan's best comic from a career of excellent work, and it suggests where she can go in the future. My main worry now is that she may end up seduced away from comics to film--Modan would be a great screenwriter/director.

by

by

, Horrock's graphic novel that posited that there was an secret art history of comics. That Horrocks continually creates major works about cartoonists and comics may seem solopsistic, and the character Sam does in many ways seem to be a stand-in for Horrocks himself. But the work is playful in the same way that If on a winter's night a traveler is playful, and that draws me in.

, Horrock's graphic novel that posited that there was an secret art history of comics. That Horrocks continually creates major works about cartoonists and comics may seem solopsistic, and the character Sam does in many ways seem to be a stand-in for Horrocks himself. But the work is playful in the same way that If on a winter's night a traveler is playful, and that draws me in. directed by Drew DeNicola and Oliva Mori

directed by Drew DeNicola and Oliva Mori  with an essay by Robert Storr (Hatje Cantz/David Zwirner)

with an essay by Robert Storr (Hatje Cantz/David Zwirner) by Yuichi Yokoyama (PictureBox)

by Yuichi Yokoyama (PictureBox)