Robert Boyd

In the lead up to Comics: Works from the Collection of Robert Boyd (March 14 to April 11 in the EMERGEncy Room at Rice University), I want to spend a little time thinking about and writing about comics. I'm always reading new comics and at any given time have a stack of not-yet-read comics (sharing space with not-yet-read novels and not-yet-read art books). Despite my looming tower of unread books, I have actually managed to finish a few, including some which were excellent.

Now most of these comics were published last year. You see, I tend to take a long time to get around to reading my comics, and once I do, I take a long time to review them. Nonetheless, I hope these reviews will be useful.

![]()

The Song of Roland by Michel Rabagliati (Conundrum Press, 2012). This is the fifth volume of autobiographical comics by Michel Rabagliati. Rabagliati came to comics through his illustration career (apparently he was hired to create a logo for Drawn & Quarterly, the art comics publisher, in 1990 when it was just beginning, and this gig sparked an renewed interest in comics on his behalf). Perhaps because he doesn't come to comics via underground/alternative comics, his conception of autobiography is quite distinct from the unflinching self-examination that characterizes the work of, say, Chester Brown. In fact, even though he is usually the main character, he has plenty of time for everyone else in who he comes in contact with in his stories. And in The Song of Roland, he turns the camera mostly away from himself and on his father-in-law, Roland, as he slowly dies of pancreatic cancer. It's a moving story, all the more powerful for being so familiar for persons of a certain age (Rabagliati is three years older than I am).

His drawing stye is stylized and fairly slick, and his storytelling is mostly pretty conventional. It reads easily, eschewing experimentation and formal trickery. Each of the books centers around one important passage in his life--losing his virginity, moving away from home, the death of a parent, but they are pleasingly discursive. Even in The Song of Roland, which deals with such a serious topic, Rabagliati throws in some slapstick about adjusting to the internet (necessary for his illustration career) and moving into his first house with his wife and daughter. And that works, because these important passages (such as a death of a close family member) always happen while you're living your life. Rabagliati is a very warm-hearted cartoonist.

![]()

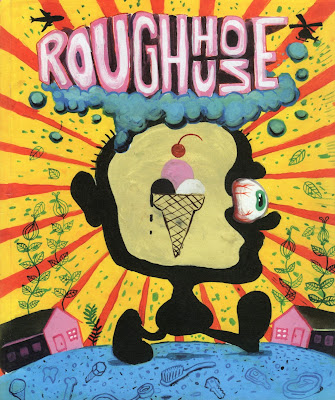

Roughhouse edited by William Kauber and featuring William Cardini, Aaron Whitiker,Brendan Keifer, Gillian Rhodes, Katie Rose Pipkin, Colin Zelinski, Tyler Sudor, Alex Webb, Sophie Roach, Douglas Pollard, Connor Shea, Blake Bohls, Baylor Estes and Matt Rebholz (Raw Paw, 2013). This squarebound anthology is the newest item in this review; I picked it up on March 2 at Staple! in Austin, and they told me they had just picked it up from the bindery that morning. The book was printed by "risograph," a digital printing technique that apparently combines elements of xerography and mimeographs. It allows them to do two and occasionally three-color printing, but the quality is fairly crude. But in Roughhouse, that works. These are impolite comics, not quite housebroken. They come out of the tradition of Weirdo, the great 80s anthology edited by Robert Crumb, Peter Bagge and Aline Kominsky-Crumb. The quality of the stories varies wildly, and many of them eschew such bourgeois values as "endings" and "having a point." But a lot of them are really good, and on balance I liked Roughhouse a lot.

Standout stories included "The Disappearing Food Truck" by Aaron Whitaker, which takes the old EC horror story structure and wittily recontextualizes it for present-day Austin; "The Thing That Was Trying to Hide" by Brendan Kiefer, in which the train of the story keeps getting interrupted in a manner that recalls If on a Winter's Night a Traveler; Sophie Roach's almost completely abstract untitled comic story; and Douglas Pollard's bizarre "Output," a story that perfectly recaptures the Weirdo vibe.

Now where you get this comic, I don't know. If you're in Austin, you can try Austin Books and Comics--they seem pretty good about carrying this kind of thing. Otherwise, email Raw Paw at rawpawzine@gmail.com and hope for the best. UPDATE: I'm told that Roughhouse will have its official launch at Farewell Books in Austin on March 6 at 6 pm. If you're in Austin, swing by and check it out!

![]()

New York Drawings by Adrian Tomine (Drawn & Quarterly, 2012). It's a bit of a cheat to include New York Drawings in this list. It's mostly an art book with a total of seven pages of comics in it. But Tomine is best known for his comics--he's been a star of the alternative comics scene for decades. (I reviewed his minicomic Optic Nerve for The Comics Journal in 1991 or 1992, when Tomine was still a teenager). Most of the art in here is work he did for The New Yorker--quite a few covers, but primarily illustrations for the listings and for reviews. Naturally he draws some very familiar faces--movie stars, musicians, etc. These are the least interesting of the work here. Best are his illustrations that try to capture a bit of life in New York City. He prettifies things quite a lot--his New York doesn't seem to be very dirty and is filled with attractive people. This may not be the most honest depiction of New York, but it's one that we can fantasize about.

A friend of mine once called Tomine the Sal Buscema of alternative comics, and coming from a comics nerd, that is not a compliment. His drawing style is blandly realistic and deadpan. But I've always been drawn to it, and here he adds an additional element beyond what we see in his comics--color. He uses a flat, Tintin-like coloring style, and his choice of colors is subtle and beautiful. The drawings here are lovely, but they make me long for a full-color comic from Tomine. That would be magnificent.

![]()

The Infinite Wait and Other Stories by Julia Wertz (Koyama Press, 2012). This is my first Julie Wertz book, even though she has done others. The drawing is a bit awkward. It's functional but not much more. But her comics are really very funny, which makes up for less-than-dazzling artwork. Wertz has a sarcastic, funny quip for every situation she finds herself in. There used to be a feature in MAD Magazine when I was a kid called "Snappy Answers to Stupid Questions." The Infinite Wait reads like "Snappy Answers to Stupid Questions" with a plot. As I read it, I kept thinking that comics was just going to be a stop along her career--she'd end up writing for television or movies eventually. Obviously words are where her talents lie. But she apparently anticipated this--her first story, "Industry," includes a section when Wertz is unable to write a script even though she has interest from a major film studio. At the end of the story, which catalogs her work history from childhood to the present, her character says the least sarcastic thing in the whole book, "I mean, when I found comics, I knew instantly that it was what I wanted to do. It just felt right. And now that I'm actually a cartoonist and it's working, I want to ride it out as long as I can."

Even though Wertz is a comic writer (comic in the sense of "funny"), she's not shy about revealing painful things--her alcoholism (and how it resulted in her losing three jobs in a row), her lupus, etc. In this way she is part and parcel with the tradition of confessional autobiographical comics started by Justin Green with Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary (1972) and continued in the work of Chester Brown and Joe Matt in the 1980s and 90s.

![]()

Are You My Mother?: A Comic Drama by Alison Bechdel (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012). Alison Bechdel's work sneaks up on me. The subject matter often seems designed to make me lose interest, and yet I get sucked in. Her comic strip, Dykes to Watch Out For, was about the lives of a group of friends, politically active left-wing lesbians. When I first looked at it, it felt overwhelmingly politically correct. But as I read, it became clear that she was depicting individuals within a subculture, and their complex negotiation of that particular subculture was shown with good deal of humor and irony. And I ended up loving these characters! (Except Mo, who remained irritating to the end.)

The same is true with Are You My Mother?, a memoir about Bechdel's fraught relationship with her mother. She deals with this relationship through psychoanalysis (which strikes me as boring), she draws (and interprets) lots of her dreams (and there is nothing less interesting than other people's dreams), with lengthy digressions into the life and work of English psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott (wha--?) and the novels of Virginia Woolf. It sounds like a recipe for disaster! But by the end of it, I felt like I was right there on the couch with Bechdel, was utterly fascinated by Winnicott, and was ready to reread Woolf (whose books I like anyway, so that's not so bad). This book won me over completely.

I think a lot of people in the alternative comics world have a problem with Bechdel--too wordy, too political, they don't like her drawing. She has a level of erudition that many comics fans might be threatened by or feel is pretentious. I think some of this attitude toward her work happens because she came to comics out of a completely different soil than that of the usual alternative comics fan or reader. She didn't grow up reading underground comics or Love & Rockets and isn't steeped in that particular history. But I think that if these skeptical readers view it this way, even unconsciously, they will be denying themselves the pleasure of reading a brilliant cartoonist.

![Share]()

In the lead up to Comics: Works from the Collection of Robert Boyd (March 14 to April 11 in the EMERGEncy Room at Rice University), I want to spend a little time thinking about and writing about comics. I'm always reading new comics and at any given time have a stack of not-yet-read comics (sharing space with not-yet-read novels and not-yet-read art books). Despite my looming tower of unread books, I have actually managed to finish a few, including some which were excellent.

Now most of these comics were published last year. You see, I tend to take a long time to get around to reading my comics, and once I do, I take a long time to review them. Nonetheless, I hope these reviews will be useful.

The Song of Roland by Michel Rabagliati (Conundrum Press, 2012). This is the fifth volume of autobiographical comics by Michel Rabagliati. Rabagliati came to comics through his illustration career (apparently he was hired to create a logo for Drawn & Quarterly, the art comics publisher, in 1990 when it was just beginning, and this gig sparked an renewed interest in comics on his behalf). Perhaps because he doesn't come to comics via underground/alternative comics, his conception of autobiography is quite distinct from the unflinching self-examination that characterizes the work of, say, Chester Brown. In fact, even though he is usually the main character, he has plenty of time for everyone else in who he comes in contact with in his stories. And in The Song of Roland, he turns the camera mostly away from himself and on his father-in-law, Roland, as he slowly dies of pancreatic cancer. It's a moving story, all the more powerful for being so familiar for persons of a certain age (Rabagliati is three years older than I am).

His drawing stye is stylized and fairly slick, and his storytelling is mostly pretty conventional. It reads easily, eschewing experimentation and formal trickery. Each of the books centers around one important passage in his life--losing his virginity, moving away from home, the death of a parent, but they are pleasingly discursive. Even in The Song of Roland, which deals with such a serious topic, Rabagliati throws in some slapstick about adjusting to the internet (necessary for his illustration career) and moving into his first house with his wife and daughter. And that works, because these important passages (such as a death of a close family member) always happen while you're living your life. Rabagliati is a very warm-hearted cartoonist.

Roughhouse edited by William Kauber and featuring William Cardini, Aaron Whitiker,Brendan Keifer, Gillian Rhodes, Katie Rose Pipkin, Colin Zelinski, Tyler Sudor, Alex Webb, Sophie Roach, Douglas Pollard, Connor Shea, Blake Bohls, Baylor Estes and Matt Rebholz (Raw Paw, 2013). This squarebound anthology is the newest item in this review; I picked it up on March 2 at Staple! in Austin, and they told me they had just picked it up from the bindery that morning. The book was printed by "risograph," a digital printing technique that apparently combines elements of xerography and mimeographs. It allows them to do two and occasionally three-color printing, but the quality is fairly crude. But in Roughhouse, that works. These are impolite comics, not quite housebroken. They come out of the tradition of Weirdo, the great 80s anthology edited by Robert Crumb, Peter Bagge and Aline Kominsky-Crumb. The quality of the stories varies wildly, and many of them eschew such bourgeois values as "endings" and "having a point." But a lot of them are really good, and on balance I liked Roughhouse a lot.

Standout stories included "The Disappearing Food Truck" by Aaron Whitaker, which takes the old EC horror story structure and wittily recontextualizes it for present-day Austin; "The Thing That Was Trying to Hide" by Brendan Kiefer, in which the train of the story keeps getting interrupted in a manner that recalls If on a Winter's Night a Traveler; Sophie Roach's almost completely abstract untitled comic story; and Douglas Pollard's bizarre "Output," a story that perfectly recaptures the Weirdo vibe.

Now where you get this comic, I don't know. If you're in Austin, you can try Austin Books and Comics--they seem pretty good about carrying this kind of thing. Otherwise, email Raw Paw at rawpawzine@gmail.com and hope for the best. UPDATE: I'm told that Roughhouse will have its official launch at Farewell Books in Austin on March 6 at 6 pm. If you're in Austin, swing by and check it out!

New York Drawings by Adrian Tomine (Drawn & Quarterly, 2012). It's a bit of a cheat to include New York Drawings in this list. It's mostly an art book with a total of seven pages of comics in it. But Tomine is best known for his comics--he's been a star of the alternative comics scene for decades. (I reviewed his minicomic Optic Nerve for The Comics Journal in 1991 or 1992, when Tomine was still a teenager). Most of the art in here is work he did for The New Yorker--quite a few covers, but primarily illustrations for the listings and for reviews. Naturally he draws some very familiar faces--movie stars, musicians, etc. These are the least interesting of the work here. Best are his illustrations that try to capture a bit of life in New York City. He prettifies things quite a lot--his New York doesn't seem to be very dirty and is filled with attractive people. This may not be the most honest depiction of New York, but it's one that we can fantasize about.

A friend of mine once called Tomine the Sal Buscema of alternative comics, and coming from a comics nerd, that is not a compliment. His drawing style is blandly realistic and deadpan. But I've always been drawn to it, and here he adds an additional element beyond what we see in his comics--color. He uses a flat, Tintin-like coloring style, and his choice of colors is subtle and beautiful. The drawings here are lovely, but they make me long for a full-color comic from Tomine. That would be magnificent.

The Infinite Wait and Other Stories by Julia Wertz (Koyama Press, 2012). This is my first Julie Wertz book, even though she has done others. The drawing is a bit awkward. It's functional but not much more. But her comics are really very funny, which makes up for less-than-dazzling artwork. Wertz has a sarcastic, funny quip for every situation she finds herself in. There used to be a feature in MAD Magazine when I was a kid called "Snappy Answers to Stupid Questions." The Infinite Wait reads like "Snappy Answers to Stupid Questions" with a plot. As I read it, I kept thinking that comics was just going to be a stop along her career--she'd end up writing for television or movies eventually. Obviously words are where her talents lie. But she apparently anticipated this--her first story, "Industry," includes a section when Wertz is unable to write a script even though she has interest from a major film studio. At the end of the story, which catalogs her work history from childhood to the present, her character says the least sarcastic thing in the whole book, "I mean, when I found comics, I knew instantly that it was what I wanted to do. It just felt right. And now that I'm actually a cartoonist and it's working, I want to ride it out as long as I can."

Even though Wertz is a comic writer (comic in the sense of "funny"), she's not shy about revealing painful things--her alcoholism (and how it resulted in her losing three jobs in a row), her lupus, etc. In this way she is part and parcel with the tradition of confessional autobiographical comics started by Justin Green with Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary (1972) and continued in the work of Chester Brown and Joe Matt in the 1980s and 90s.

Are You My Mother?: A Comic Drama by Alison Bechdel (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012). Alison Bechdel's work sneaks up on me. The subject matter often seems designed to make me lose interest, and yet I get sucked in. Her comic strip, Dykes to Watch Out For, was about the lives of a group of friends, politically active left-wing lesbians. When I first looked at it, it felt overwhelmingly politically correct. But as I read, it became clear that she was depicting individuals within a subculture, and their complex negotiation of that particular subculture was shown with good deal of humor and irony. And I ended up loving these characters! (Except Mo, who remained irritating to the end.)

The same is true with Are You My Mother?, a memoir about Bechdel's fraught relationship with her mother. She deals with this relationship through psychoanalysis (which strikes me as boring), she draws (and interprets) lots of her dreams (and there is nothing less interesting than other people's dreams), with lengthy digressions into the life and work of English psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott (wha--?) and the novels of Virginia Woolf. It sounds like a recipe for disaster! But by the end of it, I felt like I was right there on the couch with Bechdel, was utterly fascinated by Winnicott, and was ready to reread Woolf (whose books I like anyway, so that's not so bad). This book won me over completely.

I think a lot of people in the alternative comics world have a problem with Bechdel--too wordy, too political, they don't like her drawing. She has a level of erudition that many comics fans might be threatened by or feel is pretentious. I think some of this attitude toward her work happens because she came to comics out of a completely different soil than that of the usual alternative comics fan or reader. She didn't grow up reading underground comics or Love & Rockets and isn't steeped in that particular history. But I think that if these skeptical readers view it this way, even unconsciously, they will be denying themselves the pleasure of reading a brilliant cartoonist.