Robert Boyd

Art critic Thomas McEvilley died Saturday, March 2. It's hard for me to put into words how much he meant to me as a teacher and a thinker. I first encountered him as an undergraduate at Rice. I took his class on film history, which consisted of him showing a series of films and talking about each one briefly. He had olympian disdain for any films that smacked of commercial intent--we saw virtually nothing that came out of the Hollywood studio system, for example. He justified this be explaining that he was teaching "the art history of film history." This statement has stuck with me ever since because it implied that there were many histories or any given artform. So I've become interested in, for example, the economic history of art and the social history of art--subjects that may overlap with art history but are not identical. Likewise, I've always thought that thinking about comics should be done from the point of view of art history--that an art history of comics is more interesting (to me, at least), than other histories.

(It literally just occurred to me as I write that that the upcoming small exhibit of original comics art from my personal collection, Comics, mirrors McEvilley's film history class. In the class, he showed a number of silent films that could reasonably be called popular entertainment but within which the art of filmmaking was being invented. But instead of then segueing into the studio film, he skipped ahead to Italian Neorealism then to Nouvelle Vague and so on. In Comics, I devote about half of the exhibit to comic strips (mostly pre-1960s), and then skip over "mainstream" comics straight to the alternative and art comics of the 1980s to the present. I think it was McEvilley who provided this model--to create a different art history of comics from the one that is usually told. And given this, it only seems right to dedicate the exhibit to his memory.)

His other class was "Art and the Mind." In contrast to the film history class, this one was information rich. The content of this class mirrored to a certain extent the content of his later books. I took the class in the mid-80s. Art & Discontent and Art & Otherness were published in 1991 and 1992. The books themselves consisted of articles and essays he wrote, often for Artforum but also in various museum catalogs. Despite their scattered origins, they hold together quite well as books. And anyone who took "Art and the Mind" will find what he says in these books quite familiar.

![]()

Art and Discontent (1991) deals primarily with the way that art acquired a religious regard after the Enlightenment took down religion itself. McEvilley contends that art was given a phony aura of divinity by certain philosophers (he references Kant in particular) and talks about Modernism's ascent towards an idea of the sublime, which for McEviley is a mistake because it takes art out out of the realm of the real, a theme he will return to over and over. (The title of this post comes from an essay in this book.)

![]()

Art and Otherness: Crisis in Cultural Identity (1992) features his famous review of the Museum of Modern Art's "Primitivism" in the Twentieth Century, "Doctor, Lawyer, Indian Chief." This review eviscerated that show--a monument of scholarship that nonetheless turned the non-western cultures that produced works that inspired the Modernists into artistic spear carriers (in more than one way) in the drama of Modernism. This is the review that Jerry Saltz claims jump-started multiculturalism. That may be claiming too much, but curators William Ruben and Kirk Varnedoe unwisely responded to Artforum, which gave McEvilley another go. It was a knockout blow. (So thorough was his victory that he outsourced his evisceration of Varnedoe's MOMA sequel, High and Low: Modern Art and Popular Culture, to two other critics from his perch as editor of Contemporania.) This book expands on the ideas present in that review.

![]()

The Exile's Return: Toward a Redefinition of Painting for the Postmodern Era (1993) follows right on the heels of the previous two books and perhaps because of that has the most straightforward concept. Painting, for centuries the primary Western art form, ceased to be so around 1965 due to a crisis of legitimacy. But in 1980, it came back--chastened in many ways--as a newly revitalized form. Given this thesis, McEvilley is able to reprint a variety of excellent reviews and catalog essays about painters, including Agnes Martin, Robert Ryman, and surprisingly in a way, certain Neo-Expressionists like Georg Baselitz and Julian Schnabel.

![]()

For some reason, there is a big time gap before McEvilley's next art book, Sculpture in the Age of Doubt(1999).And perhaps for that reason, it is a much denser book which essentially walks the reader through a history of Western thought (with big dollops of Buddhist thought added)before talking about sculpture. His main subject is a Greek philosophy called Pyrrhonism which was based on radical doubt. McEvilley saw sculpture as more easily embodying this kind of doubt (which he saw as necessary for ending the Kantian/Hegelian project of Modernism) than painting. Indeed, he suggests that painting, by wishing to become "objects" instead of illusions, wants to be sculpture. So you go 68 pages into Sculpture in the Age of Doubt before he talks about any specific sculptures. Interestingly, while he discusses the work of well-known international artists like Marcel Broodthears, Jannis Kounellis, Anish Kapoor, etc., he touches on artists with a local connection (that is, Texas/Houston) like Michael Tracy and Mel Chin. Even though his ties to Houston got less and less over time (he was hired as a young PhD in 1969 by the Menils to teach at Rice--by the time I took his classes in the 80s, he was commuting from New York City), he still knew many in the artistic community and supported their work. As late as 2004, he wrote an essay for a show of work by Houston painter Richard Stout.

![]()

Now it may seem strange that a critic so devoted to overthrowing the hitherto timeless verities of the Modernist project would write books about such traditional artforms as painting and sculpture. Sculpture had come to be so broadly defines that it could be almost anything, but what about art that was dematerialized, that existed as a process or a ritual, rather than a thing? That was the subject of the next one on the series, The Triumph of Anti-Art: Conceptual and Performance Art in the Formation of Post-Modernism, published in 2005 after another seemingly long wait. (At least, it felt long to me.) Again Pyrrhon is a philosophical touchstone, especially for his direct influence on Duchamp, who McEvilley sees as the father of "anti-art." Opposed to Pyrrhon is Kant. For McEvilley, Kant's big problem is that he separated art off from other human endeavors in his Critique of Judgment. The aesthetic is separated off from the cognitive (Critique of Pure Reason) and the ethical (Critique of Practical Reason). (I will take McEvilley's word for it because after reading Foundations of the Metaphysics of Morals in college, I decided I had read enough Kant.) McEvilley seeks to reclaim the cognitive and ethical for art, and places conceptual art within the cognitive sphere and performance art within the ethical sphere (to simplify his much more subtle arguments). The rest of the book is a discussion of specific artists and works.

Now at this point, you might be asking yourself, what about theory and shit? McEvilley wrote a lot about philosophy, but it was all really old philosophy. He rarely mentions Derrida, Baudrillard, Deleuze, Foucault, Kristeva or any of those mostly French big brains whose work underpins so much art criticism and theory of the last thirty years. I mean, McEvilley is a monster of erudition--he seems to have read everything. So why not refer to the really current theory in his work?

I think it's because he thought it was old hat. He knew so much about Greek and Indian philosophy (he read them in Greek and Sanskrit, about which more later) that when he saw contemporary Post-Structuralist philosophy, he saw echoes of other thought expressed thousands of years ago. For the reader, this meant that McEvilley's work was blessedly free of super-difficult post-structuralist jargon. That is not to say that it was easy reading, but it didn't have that unnecessary extra layer of cant--the kind of writing that has come to be known as "international art English." McEvilley's prose was, in contrast, pretty straight-forward.

![]()

McEvilley returned in 2010 with Art, Love, Friendship: Marina Abramovic and Ulay Together & Apart, a book that seemed design to cash in on the sudden unexpected popularity of Marina Abramovic, but in some ways is his most personal book because it deals with his friendship with Ulay and Abramovic and their relationship with each other, through art. The centerpiece is a long account of Abramovic and Ulay's Great Wall performance, where they walked the length of the Great Wall of China starting at opposite ends until they met at the middle. McEvilley accompanied them for part of the way. This was their last piece together--the meeting would, ironically, be a farewell. And there is a sense in McEvilley's account of that familiar awkward feeling of being a friend of a couple that is breaking up.

![]()

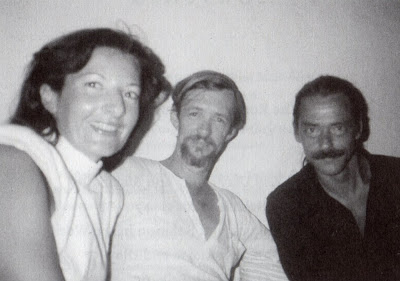

Marina Abramovic, Thomas McEvilly and Ulay from Art, Love, Friendship

These books are collectively a great work of art criticism and theory that for me form a basis or jumping off point for thinking about art. There are aspects or tendencies of McEvilley's thought I disagree with, but usually when I think about contemporary art, I'm bouncing it off him in my mind. It's like I'm having a discussion with him (and I can hear his unique voice--you can, too in this excellent video from 2000). But the crazy thing is that these books were kind of a side project for him. His main project--his life's work, really--was a comparative study of Greek and Indian philosophy called The Shape of Ancient Thought. (I've never read it and probably never will, but the video I linked to outlines it very well.)

Jerry Saltz writes wittily about auditing McEvilley's classes at the School of Visual Arts, poet Charles Bernstein wrote an excellent obituary, and Rainey Knudson writes about taking "Art and the Mind" at Rice in a post that stirred up many memories for me. I suspect there will be other tributes in the days to come. But the best tribute to McEvilley would be to read his books. It's been 20-odd years since I read Art & Discontent--I think it's about time to read it again.

![Share]()

Art critic Thomas McEvilley died Saturday, March 2. It's hard for me to put into words how much he meant to me as a teacher and a thinker. I first encountered him as an undergraduate at Rice. I took his class on film history, which consisted of him showing a series of films and talking about each one briefly. He had olympian disdain for any films that smacked of commercial intent--we saw virtually nothing that came out of the Hollywood studio system, for example. He justified this be explaining that he was teaching "the art history of film history." This statement has stuck with me ever since because it implied that there were many histories or any given artform. So I've become interested in, for example, the economic history of art and the social history of art--subjects that may overlap with art history but are not identical. Likewise, I've always thought that thinking about comics should be done from the point of view of art history--that an art history of comics is more interesting (to me, at least), than other histories.

(It literally just occurred to me as I write that that the upcoming small exhibit of original comics art from my personal collection, Comics, mirrors McEvilley's film history class. In the class, he showed a number of silent films that could reasonably be called popular entertainment but within which the art of filmmaking was being invented. But instead of then segueing into the studio film, he skipped ahead to Italian Neorealism then to Nouvelle Vague and so on. In Comics, I devote about half of the exhibit to comic strips (mostly pre-1960s), and then skip over "mainstream" comics straight to the alternative and art comics of the 1980s to the present. I think it was McEvilley who provided this model--to create a different art history of comics from the one that is usually told. And given this, it only seems right to dedicate the exhibit to his memory.)

His other class was "Art and the Mind." In contrast to the film history class, this one was information rich. The content of this class mirrored to a certain extent the content of his later books. I took the class in the mid-80s. Art & Discontent and Art & Otherness were published in 1991 and 1992. The books themselves consisted of articles and essays he wrote, often for Artforum but also in various museum catalogs. Despite their scattered origins, they hold together quite well as books. And anyone who took "Art and the Mind" will find what he says in these books quite familiar.

Art and Discontent (1991) deals primarily with the way that art acquired a religious regard after the Enlightenment took down religion itself. McEvilley contends that art was given a phony aura of divinity by certain philosophers (he references Kant in particular) and talks about Modernism's ascent towards an idea of the sublime, which for McEviley is a mistake because it takes art out out of the realm of the real, a theme he will return to over and over. (The title of this post comes from an essay in this book.)

Art and Otherness: Crisis in Cultural Identity (1992) features his famous review of the Museum of Modern Art's "Primitivism" in the Twentieth Century, "Doctor, Lawyer, Indian Chief." This review eviscerated that show--a monument of scholarship that nonetheless turned the non-western cultures that produced works that inspired the Modernists into artistic spear carriers (in more than one way) in the drama of Modernism. This is the review that Jerry Saltz claims jump-started multiculturalism. That may be claiming too much, but curators William Ruben and Kirk Varnedoe unwisely responded to Artforum, which gave McEvilley another go. It was a knockout blow. (So thorough was his victory that he outsourced his evisceration of Varnedoe's MOMA sequel, High and Low: Modern Art and Popular Culture, to two other critics from his perch as editor of Contemporania.) This book expands on the ideas present in that review.

The Exile's Return: Toward a Redefinition of Painting for the Postmodern Era (1993) follows right on the heels of the previous two books and perhaps because of that has the most straightforward concept. Painting, for centuries the primary Western art form, ceased to be so around 1965 due to a crisis of legitimacy. But in 1980, it came back--chastened in many ways--as a newly revitalized form. Given this thesis, McEvilley is able to reprint a variety of excellent reviews and catalog essays about painters, including Agnes Martin, Robert Ryman, and surprisingly in a way, certain Neo-Expressionists like Georg Baselitz and Julian Schnabel.

For some reason, there is a big time gap before McEvilley's next art book, Sculpture in the Age of Doubt(1999).And perhaps for that reason, it is a much denser book which essentially walks the reader through a history of Western thought (with big dollops of Buddhist thought added)before talking about sculpture. His main subject is a Greek philosophy called Pyrrhonism which was based on radical doubt. McEvilley saw sculpture as more easily embodying this kind of doubt (which he saw as necessary for ending the Kantian/Hegelian project of Modernism) than painting. Indeed, he suggests that painting, by wishing to become "objects" instead of illusions, wants to be sculpture. So you go 68 pages into Sculpture in the Age of Doubt before he talks about any specific sculptures. Interestingly, while he discusses the work of well-known international artists like Marcel Broodthears, Jannis Kounellis, Anish Kapoor, etc., he touches on artists with a local connection (that is, Texas/Houston) like Michael Tracy and Mel Chin. Even though his ties to Houston got less and less over time (he was hired as a young PhD in 1969 by the Menils to teach at Rice--by the time I took his classes in the 80s, he was commuting from New York City), he still knew many in the artistic community and supported their work. As late as 2004, he wrote an essay for a show of work by Houston painter Richard Stout.

Now it may seem strange that a critic so devoted to overthrowing the hitherto timeless verities of the Modernist project would write books about such traditional artforms as painting and sculpture. Sculpture had come to be so broadly defines that it could be almost anything, but what about art that was dematerialized, that existed as a process or a ritual, rather than a thing? That was the subject of the next one on the series, The Triumph of Anti-Art: Conceptual and Performance Art in the Formation of Post-Modernism, published in 2005 after another seemingly long wait. (At least, it felt long to me.) Again Pyrrhon is a philosophical touchstone, especially for his direct influence on Duchamp, who McEvilley sees as the father of "anti-art." Opposed to Pyrrhon is Kant. For McEvilley, Kant's big problem is that he separated art off from other human endeavors in his Critique of Judgment. The aesthetic is separated off from the cognitive (Critique of Pure Reason) and the ethical (Critique of Practical Reason). (I will take McEvilley's word for it because after reading Foundations of the Metaphysics of Morals in college, I decided I had read enough Kant.) McEvilley seeks to reclaim the cognitive and ethical for art, and places conceptual art within the cognitive sphere and performance art within the ethical sphere (to simplify his much more subtle arguments). The rest of the book is a discussion of specific artists and works.

Now at this point, you might be asking yourself, what about theory and shit? McEvilley wrote a lot about philosophy, but it was all really old philosophy. He rarely mentions Derrida, Baudrillard, Deleuze, Foucault, Kristeva or any of those mostly French big brains whose work underpins so much art criticism and theory of the last thirty years. I mean, McEvilley is a monster of erudition--he seems to have read everything. So why not refer to the really current theory in his work?

I think it's because he thought it was old hat. He knew so much about Greek and Indian philosophy (he read them in Greek and Sanskrit, about which more later) that when he saw contemporary Post-Structuralist philosophy, he saw echoes of other thought expressed thousands of years ago. For the reader, this meant that McEvilley's work was blessedly free of super-difficult post-structuralist jargon. That is not to say that it was easy reading, but it didn't have that unnecessary extra layer of cant--the kind of writing that has come to be known as "international art English." McEvilley's prose was, in contrast, pretty straight-forward.

McEvilley returned in 2010 with Art, Love, Friendship: Marina Abramovic and Ulay Together & Apart, a book that seemed design to cash in on the sudden unexpected popularity of Marina Abramovic, but in some ways is his most personal book because it deals with his friendship with Ulay and Abramovic and their relationship with each other, through art. The centerpiece is a long account of Abramovic and Ulay's Great Wall performance, where they walked the length of the Great Wall of China starting at opposite ends until they met at the middle. McEvilley accompanied them for part of the way. This was their last piece together--the meeting would, ironically, be a farewell. And there is a sense in McEvilley's account of that familiar awkward feeling of being a friend of a couple that is breaking up.

Marina Abramovic, Thomas McEvilly and Ulay from Art, Love, Friendship

These books are collectively a great work of art criticism and theory that for me form a basis or jumping off point for thinking about art. There are aspects or tendencies of McEvilley's thought I disagree with, but usually when I think about contemporary art, I'm bouncing it off him in my mind. It's like I'm having a discussion with him (and I can hear his unique voice--you can, too in this excellent video from 2000). But the crazy thing is that these books were kind of a side project for him. His main project--his life's work, really--was a comparative study of Greek and Indian philosophy called The Shape of Ancient Thought. (I've never read it and probably never will, but the video I linked to outlines it very well.)

Jerry Saltz writes wittily about auditing McEvilley's classes at the School of Visual Arts, poet Charles Bernstein wrote an excellent obituary, and Rainey Knudson writes about taking "Art and the Mind" at Rice in a post that stirred up many memories for me. I suspect there will be other tributes in the days to come. But the best tribute to McEvilley would be to read his books. It's been 20-odd years since I read Art & Discontent--I think it's about time to read it again.