I Have a New Article Up at Glasstire

Homologous Cartoons

In the 19th century, mathematicians invented a new branch of mathematics, topology, the mathematics of shapes. They turned ways of thinking about shapes into a kind of algebra. One of the most important concepts in topology is "homology". Without getting into the technical aspects (which I can't claim to understand), if a shape has a certain characteristic, as long as it maintains that characteristic, that shape can be extremely deformed but remain homologous. A famous example is that a donut shape (known as a torus) is homologous to a teacup, in that they are both shapes with one hole.

Another homologous shape to a torus is a drinking straw.

I thought about homology when I saw Russell Etchen's exhibit, About Six Thousand Five Hundred Rocks, About One Thousand Five Hundred People, and Some Clover, at Bill Arning Exhibition. Etchen, who lives in Los Angeles, was a well-known figure in the Houston scene for several years, belonging to the drawing club Sketch Klubb (I'm not sure they were ever organized enough to be a "collective"), operating the great alternative bookstore Domy, and designing publications for artist Mark Flood. I first met Etchen when I moved back to Houston and worked for ADVision, the long-defunct anime company. He was a designer on their slick magazine, Newtype. In 2016, Etchen painted a mural on the north exterior wall of Lawndale Art Center consisting of hundreds of grey, cartoony rocks with white google eyes. His current exhibit seems to be a direct descendant of this earlier project.

Russell Etchen, some faces surrounded by rocks

The show consists of drawings of faces and rocks (with eyes). Some are drawn on paper, some are painted in the wall of the gallery, and a bunch are printed in a zine titled About 3400 People.

So where does homology come in? What Etchen shows is that if you have a certain consistent elements in a face, it can be almost endlessly warped and still be recognizable. This is especially apparent in the the zine.

For example, the faces on the right-hand page reproduced above all read as the same face, even though the have drastically different shapes. The Beatles-esque haircut, the little round sunglasses, the triangle nose, the open mouth with top teeth showing, and three red dimples are repeated in every face, and it is the repetitions of these elements that work on us to make all the faces the same. Every page of his zine works the same way. Despite their obvious variety, we recognize all faces on each page as the same.

This exercise demonstrates a truth about cartooning--that it is inherently different from naturalistic drawing. A cartoon character, in order to be recognizable, has to maintain certain design elements, but beyond that, the cartoonist can do just about anything. This is easy to see when you look at how popular cartoon characters have changed over time, yet remained instantly recognizable.

Charles Schulz, Charlie Brown though the years

If you are Charles Schulz, as long as you draw a figure with a round head, a tuft of hair, and a zig-zag stripe on his shirt, he is always Charlie Brown. It doesn't matter how shaky Schulz's lines got toward the end of his life.

Etchen's exercise of drawing faces this way is a perfect example of the power of cartooning. I don't know if he intended this or not, but to me, this is one of the best demonstrations of the difference between cartooning and drawing I've ever seen. I've mentioned in earlier blog posts that a lot of contemporary artists make use of characters that they go back to over and over again. For example, Trenton Doyle Hancock and JooYoung Choi. This requires that they develop homologous characteristics so that we can always recognize the characters.

Etchen's exhibit is up through the end of August, and you can buy his 'zine there for $6 (cheap!).

Fifth Ward Salute

About 10 years ago, I wrote a very brief post about a odd piece of public art in the Fifth Ward. If you read the piece, you will see that I knew nothing about this piece. There was no plaque or sign identifying the sculpture. The only marking on the sculpture was some crudely engraved letters reading "Tanya."

Today I got an email from an artist named Michael Boot. He told me that when he was an art student at UH, he had assisted in this sculpture's fabrication. The artist is named Tanya Preminger.

This photo is from Preminger's website. What I notice immediately are the trees growing out of the fingers. They weren't there in 2011. (I'll have to go check it out again sometime this week to see if the trees have been replaced.)

Preminger is an interesting artist. Born and trained in the Soviet Union, she immigrated to Israel in 1972. Her sculptures have been installed all over the world, with most being in Israel. Some of the work feels kind of jokey (which is how I would characterize Salute.) But she obviously can handle stone sculpture as a plastic medium. Here are a couple of sculptures from her website, which is well-worth exploring.

It is located at the intersection of Lyons and Sydnor.

Robert Boyd's Book Report: Frank Herbert, Doris Lessing, Primo Levi and Willie Morris

Today I looked at several books from my library.

I report on Dune by Frank Herbert, The Golden Notebook by Doris Lessing, If This is a Man, The Truce, The Periodic Table, and The Monkey's Wrench by Primo Levi, and North Toward Home by Willie Morris.

These are books from my bookshelves that I've read at different points in my life. They all come from the "literature" shelf.

By the way, you may notice a new button on this site: a Patreon button. It's on the right side of the screen (if you are looking at this one a computer) at the top of the right-hand column. I'd like to invite you to support this blog.

Robert Boyd's Book Report: Art & Revolution by John Berger

Today I'm discussing Art & Revolution by John Berger, the late English critic best known for Ways of Seeing. Art & Revolution is a critical biography of Ernst Niezvestny, an unofficial artist in the Soviet Union. He was a sculptor who eventually emigrated to the USA in 1976. (Art & Revolution was written in 1969.) I've written about Niezvestny before. I became interested in him when I first heard about him in Khrushchez: The Man and His Era by William Taubman.

(This was the first book report for which I ever wrote a script in advance, but I have to say it feels a little stiff--a little too much like a lecture I want to improve my delivery, but I'm not sure what the best way is. I'm open to advice!)

And just a reminder--press the Patreon button to the right. Or just go to this link.

Real Estate Art: 13342 Hopes Creek Road, College Station

I was intrigued flipping through HAR.com by this huge, futuristic house out near Texas A&M. I hoped they might have an art collection--a house that big on a lot that big (317 acres) has room to have some Storm King-sized sculpture. No such luck--the most sculptural thing on the property was the house itself. (At least, in the photos they showed.)

It looks like a stealth bomber landed on the prairie.

The art shown on the inside is not immediately familiar to me. If I were the type of person who could afford a seven million dollar house like this, I would invest in some sleek sculpture (maybe a Roxy Paine) and an big Julie Mehretu inside.

Here's what they have that they showed in the photos on HAR.

But I think the current owner would agree that the right kind of art for the inside of this is abstract art.

But they also display a little pretty photography.

And if the landscape visible right outside the huge windows is inadequate, they hang a couple of landscape painting.

I do not recognize any of the artists of these works, nor the architect (whose name is apparently not a selling point--it's not mentioned on HAR). Do any readers have any insight they could share?

If you like these posts, I invite you support my Patreon. It's cheap and helps me a lot.

Real Estate Art: 713 Booth Street

I am working on some new posts, but I hope this real estate art post will satisfy my few remaining readers for a little while. This is a very interesting house on the near northside, traditionally a very Hispanic neighborhood. I downloaded the map so you can see where it is:

As you can see, it is right across Little White Oak Bayou from Hollywood Cemetery and quite close to Moody Park. I don't know what kind of house you would expect in that neighborhood, but I am willing to bet that it would not be this.

That is one moderne pile of blocks!

If you are flipping through HAR.com, as I enjoy doing, and you want to guess what kind of house will have interesting art hanging inside, this is the kind of house that you would guess. And in this case, you'd be right! As usual, I didn't recognize most of the art (and mostly it is not photographed to show off the art--these photos serve an entirely different purpose). But I think I know the artist behind one of the pieces.

In this photo, we can see two paintings. On the right, we see a large abstraction that reminds me a little of Richard Diebenkorn, but is obviously not a Diebenkorn. But the painting on the stairs is, I think, by Lucas Johnson, the late Houston-based painter. I definitely could be wrong, and would appreciate finding out for sure from any of you eagle-eyed readers if it is or if it's not. Johnson was a beloved member of the local art scene. He died in 2002 from a heart attack that he suffered while on a boat fishing with fellow artist Jack Massing.

I don't recognize any of the other art in the house, but you might! If you do, please identify it in the

comments below.

I would kill for a library like that!

Another view of the library. And the painting, which appears to have paint drips or possibly loose threads hanging down look very familiar--but I can't identify it.

It has been suggested that this piece is by Deborah Roberts.

It appears that there is an easel in the background on the right of this photo. Perhaps the owner of this house is a Sunday painter?

The Houston Fall Art Season, part 1

The world of art galleries is divided into seasons. I don’t say “the art world” because I consider the gallery world to be a small subset of the art world. But traditionally, we have a fall season that starts just after Labor Day and a spring season that starts just after New Year. Summer is traditionally a dead season. (The bookselling world is divided the same way, as are school years.) I think this comes out of the New York City art gallery world, although I may be wrong. The idea was that everyone was on vacation during the summer, so it made no sense to open your big shows after Labor Day. Why this should be as true in Houston as it is in New York, I don’t know. But for a long time, we got “fall collections” of warm clothes utterly inappropriate for the volcanic heat of Houston—we take our cues from New York, whether it makes sense to do so or not.

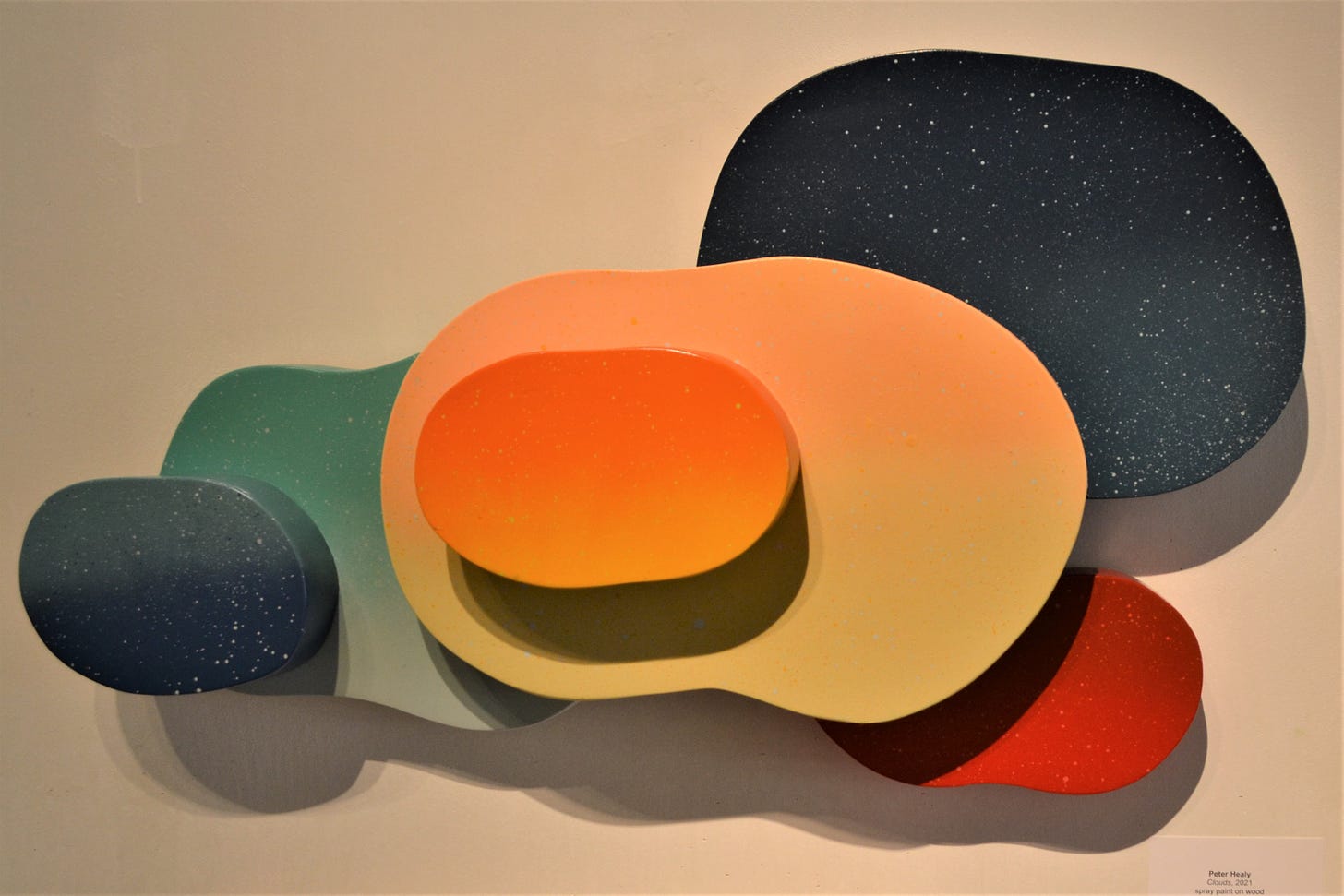

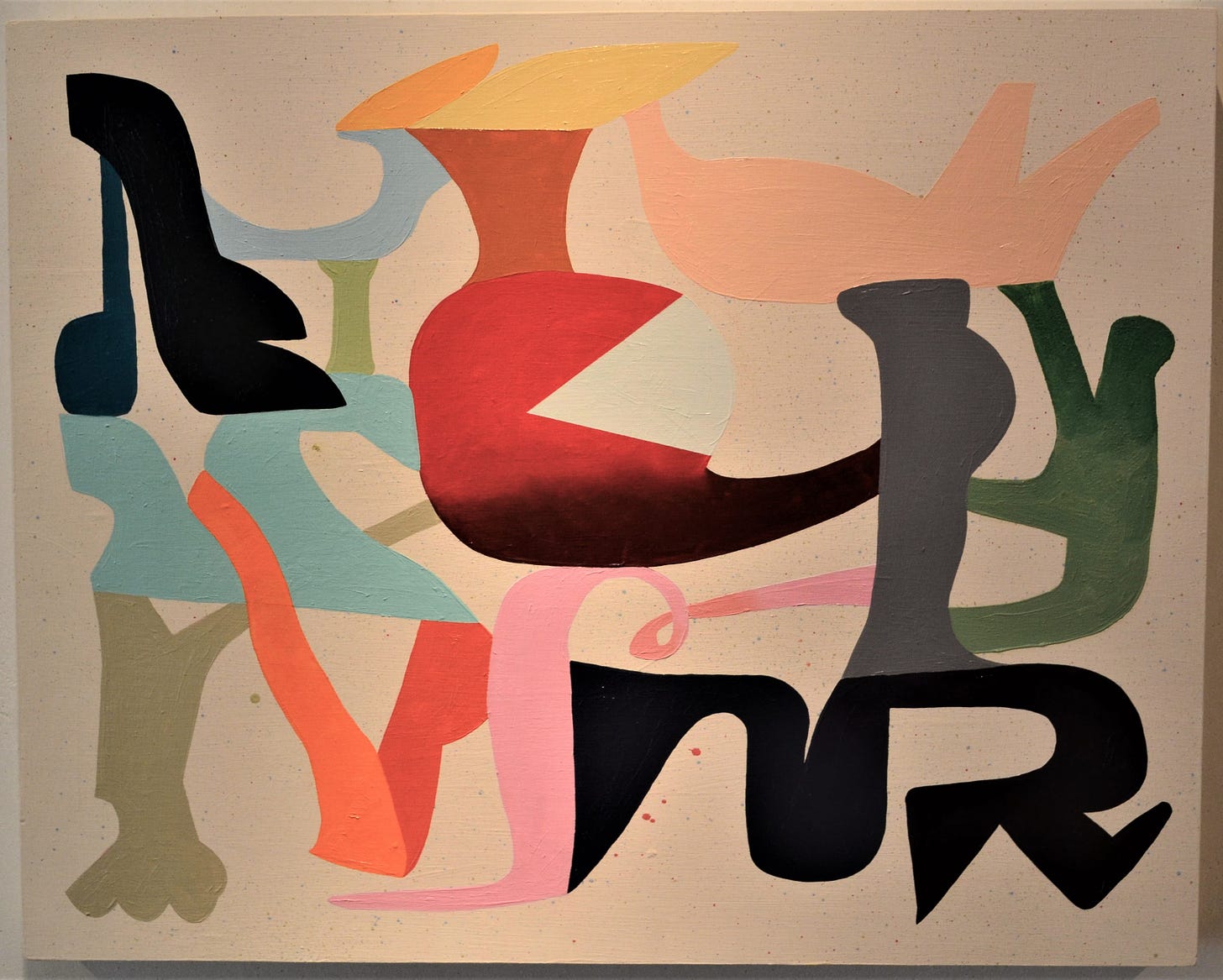

I started my personal fall art season by visiting Foltz Fine Art, the Menil Museum, the Art League, and ARC House on Friday. Let’s go through them one by one. There will be a lot of photos in this post and not much criticism. First, let’s look at the large group show at Foltz, The Show is called Texas Emerging: Volume II and featured a lot of work by six artists: Erika Alonso, Dylan Conner, Laura Garwood, Peter Healy,Matt Messinger, and Meribeth Privett. Of these six artists, I was only really familiar with Conner and Messinger, both of whom I have pieces by in my personal collection.

Connor’s work is sculptural, made with salvaged metal and creamy white polymer gypsum. The salvaged metal often has a patina or layer of rust.

I know from experience that the works are quite heavy, but what I like about them is their elegance and almost biological.

Dylan Conner, Wasteland Coral, 2019, steel from pipe with natural patina, polymer gypsum, reclaimed foundry equipment with refractory residue, partially charred hardwood timbers from pallet, and steel hardware

Dylan Conner, Wasteland Coral, 2019, steel from pipe with natural patina, polymer gypsum, reclaimed foundry equipment with refractory residue, partially charred hardwood timbers from pallet, and steel hardwareThese pieces are like pieces of random metal with abstract polyps growing out of them. And I was astonished to see them in Foltz Fine Art, since I have always thought of it as a gallery that specializes in midcentury Texas artists (like Richard Stout and Stella Sullivan, whose retrospective show I reviewed in Glasstire in 2018) and landscape art. But looking at their recent exhibits, I see that more and more of the shows have featured contemporary artists. I hope that they don’t lose their focus on early Texas modernists because they are the only commercial gallery that makes an effort to remember our regional art history. But I approve of them showing younger artists.

I missed Texas Emerging: Volume I, which going by what is on the Foltz website must have been fantastic and perhaps even more daring than this iteration of the show. Most of the artists this time around are painters (Conner being the major exception, though several of the artists have at least some three-dimensional works). I have nothing against painters, of course, and I don’t expect Foltz to start showing installation art or video art anytime soon.

One of the artists I had never heard of was Meribeth Privett, who does these large, gestural abstractions. I’m always a little surprised when I see an artist in 2021 doing abstract expressionist painting, a style that reached its zenith 60 odd years ago. But while we are mostly well and truly over post-modernism, one thing that it gifted us was to tell is that the entire history of art was ours for the plundering. If what you want to express is best expressed with a more-or-less defunct art style, go for it!

I know nothing about Privett, so I went to her website. In addition to painting, she offers up her services as a “creativity coach”. OK, I’m not exactly sure what that is. Which probably means I could use some creativity coaching.

Laura Garwood, left: Untitled (burgundy, red yellow, white), 2019, right: Untitled (Dark purple, Yellow, Pink Stripes), 2018, both are oil and acrylic on canvas

Laura Garwood, left: Untitled (burgundy, red yellow, white), 2019, right: Untitled (Dark purple, Yellow, Pink Stripes), 2018, both are oil and acrylic on canvasBarnett Newman called and wants his sublimity back. Laura Garwood is another artist I’ve never heard of. I used to have at least an inkling of pretty much every artist in Houston, but as time (and isolation) goes on, I know fewer and fewer of them. One great thing about going to all these openings was that I got a chance to reconnect with a bunch of them.

Peter Healy is another artist I don’t know personally, but I think I’ve seen his work around. As far as I can tell from various crumbs online that I’ve found, he is based in Houston but is from Northern Ireland. All of his pieces in this show were fun and attractive. Assemblage #1 is made of “found wood”, but despite that, it looks quite slick and polished compared to other assemblage artists (I’m thinking of Wallace Berman, George Herms or, here in Houston, Patrick Renner). I prefer my assemblage to feel a little more rough-hewn, a little more “street”, but Healy’s assemblages are attractive.

Healy is also a painter, producing jaunty abstractions.

These have the feel of midcentury illustration in a way.

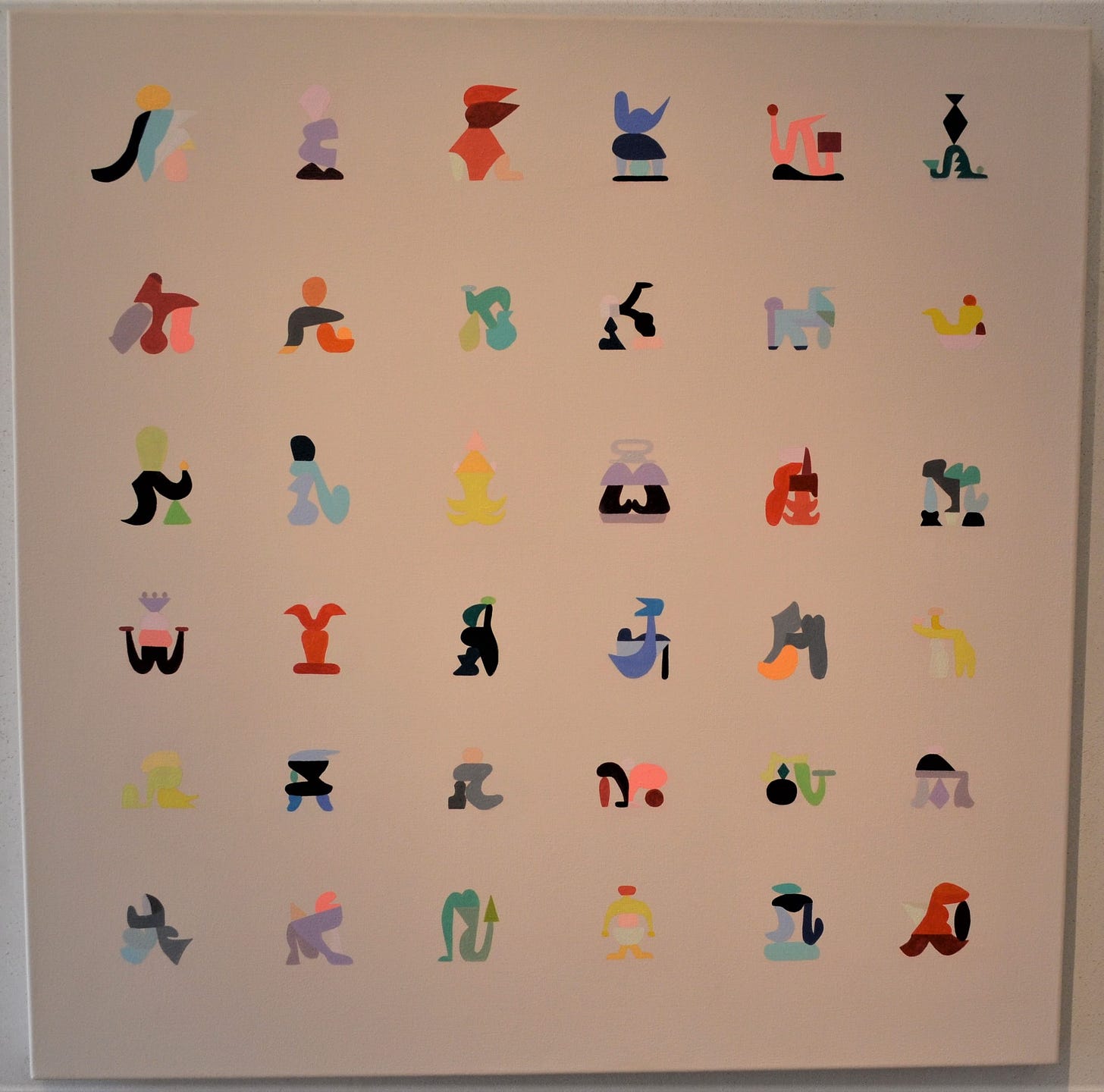

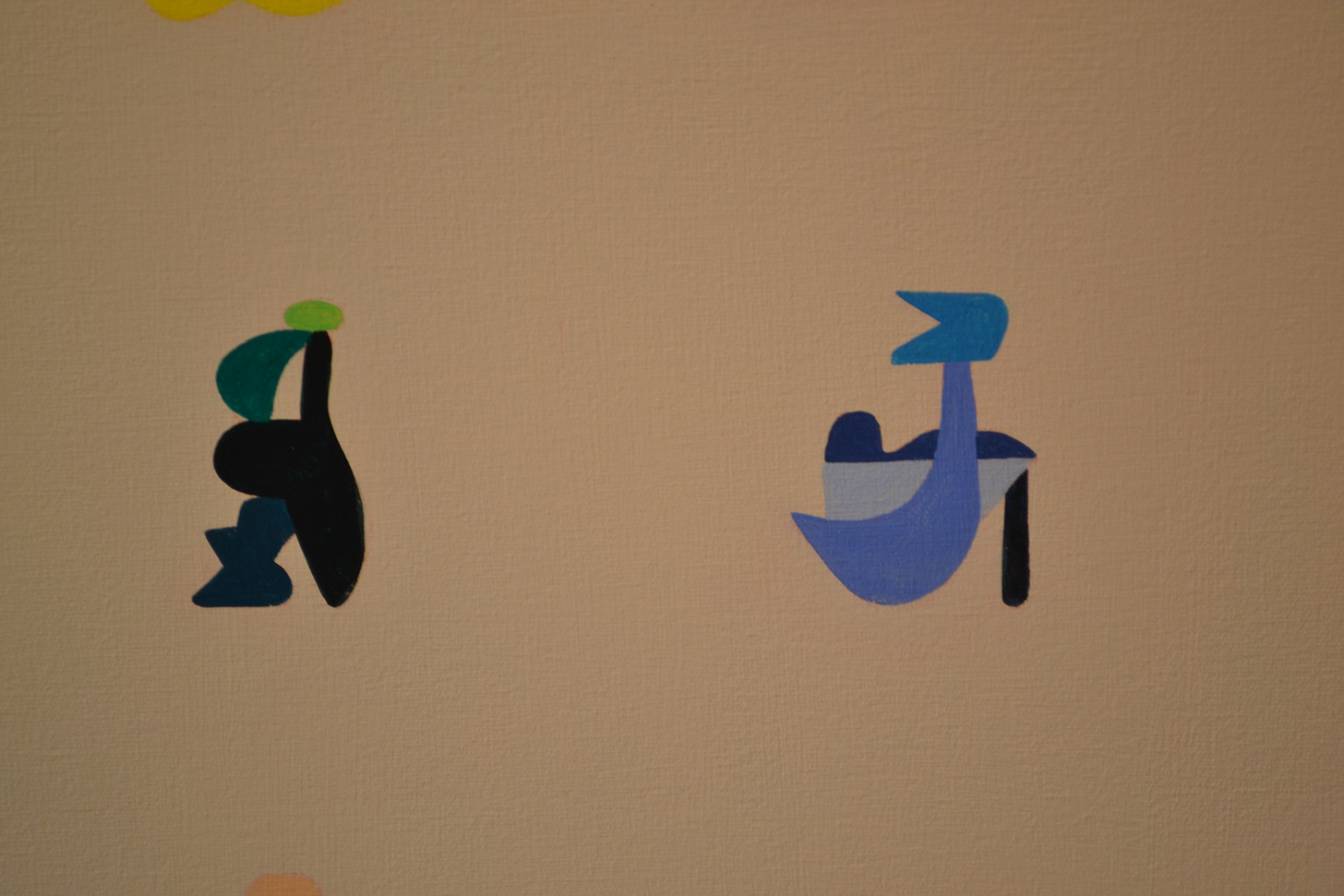

Community #2 is like a model sheet for little abstract figures for an animation.

Having seen the model sheet, I want to see the story that they star in.

This piece made with found wood has that rough hewn quality that I like.

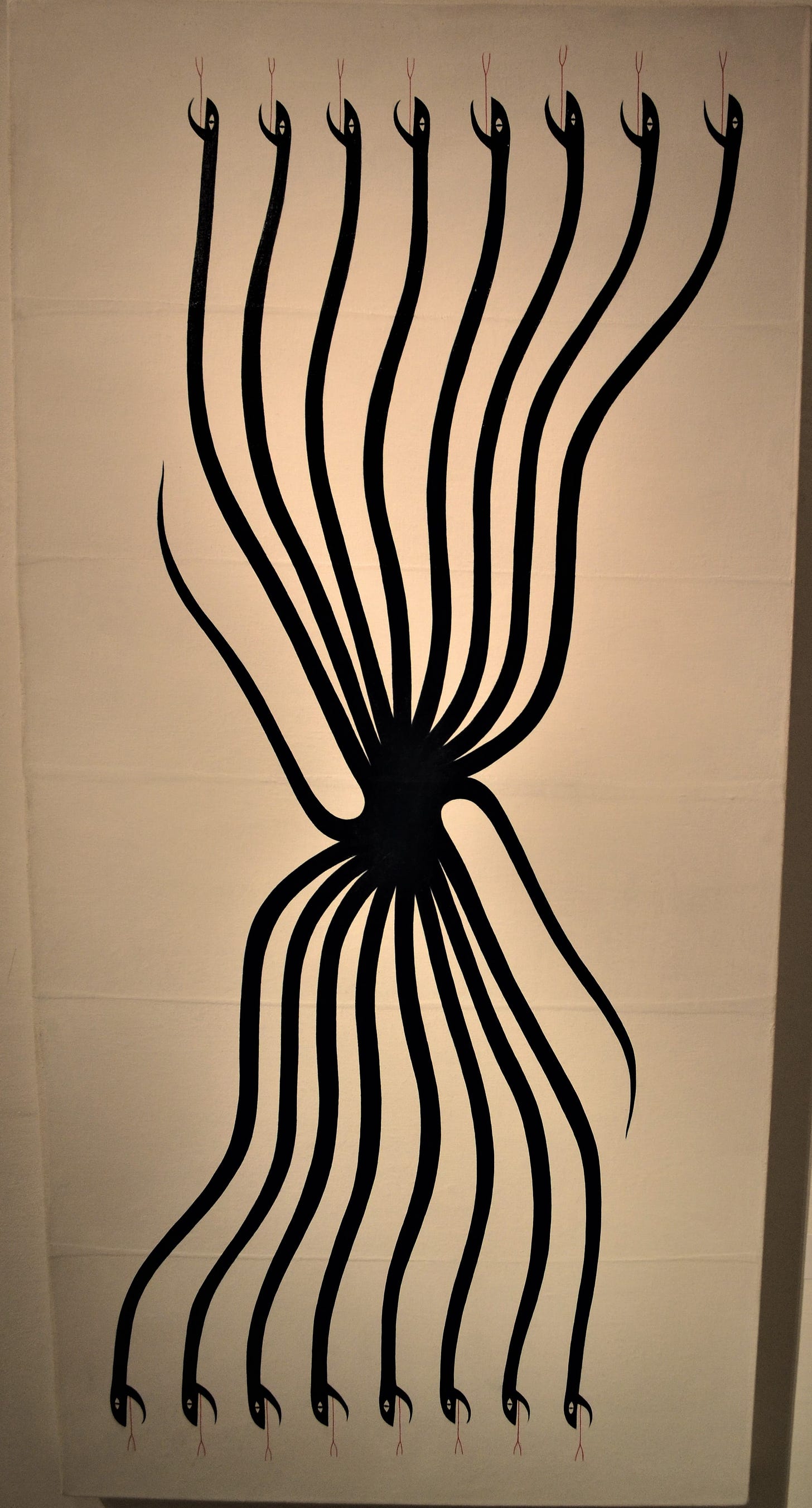

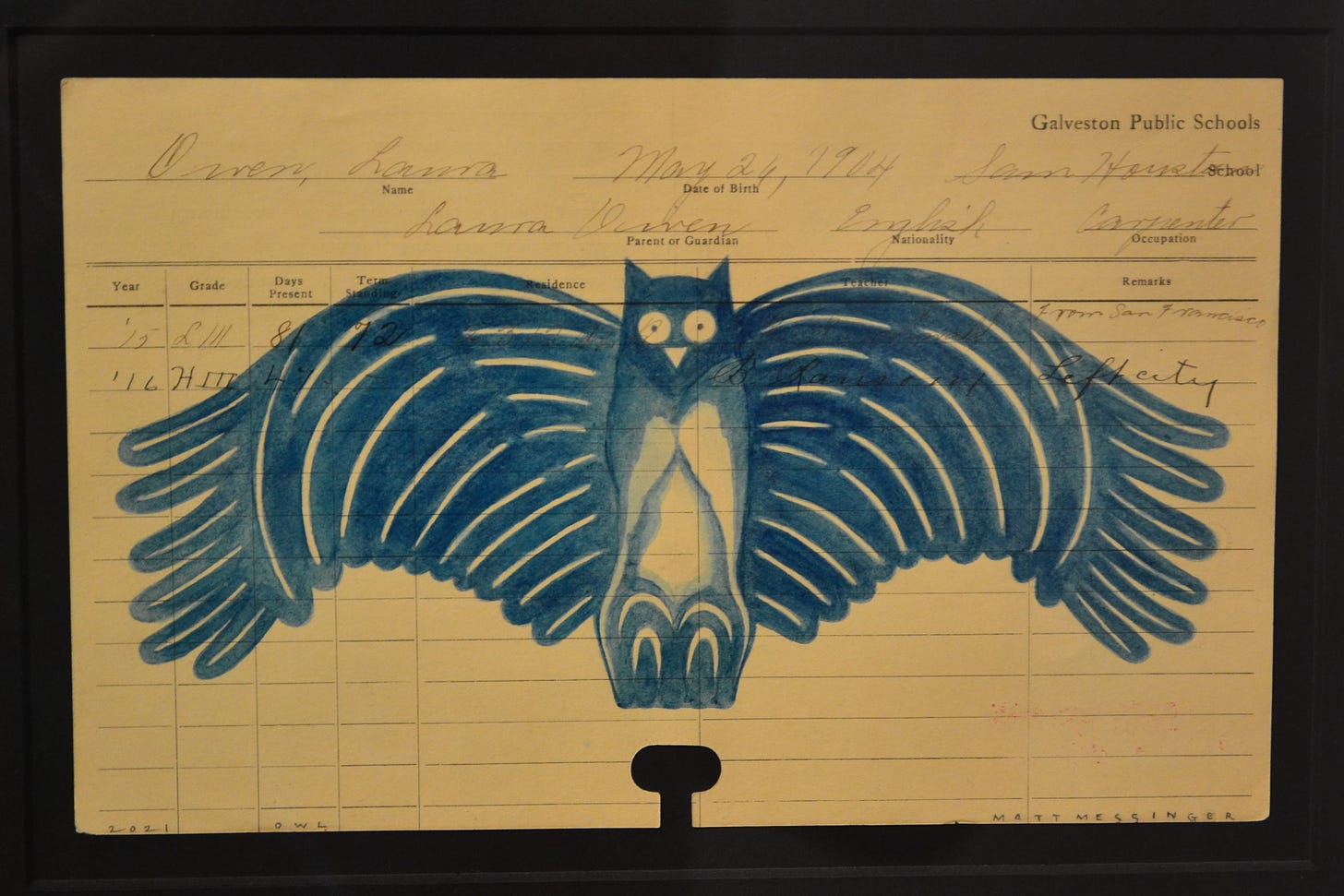

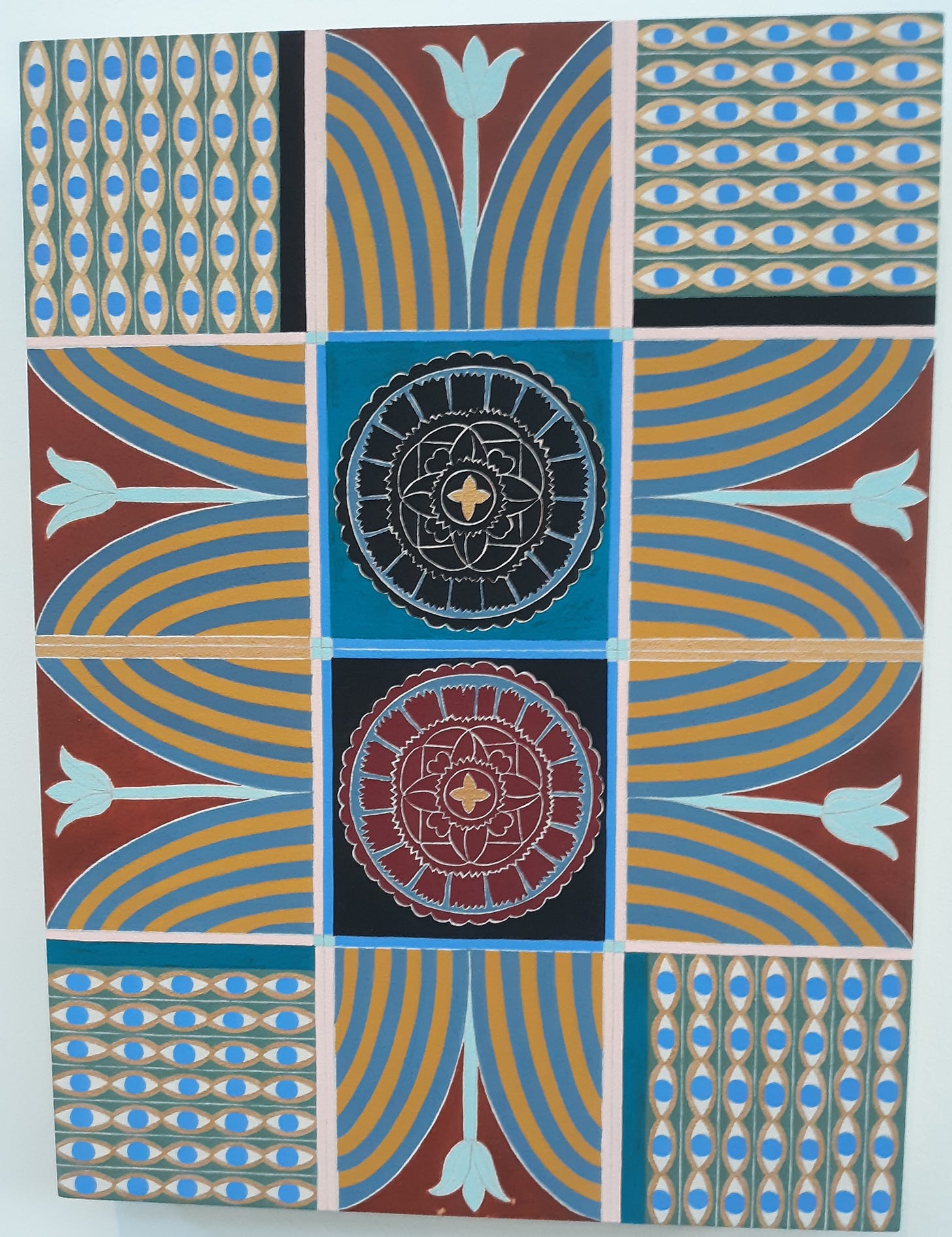

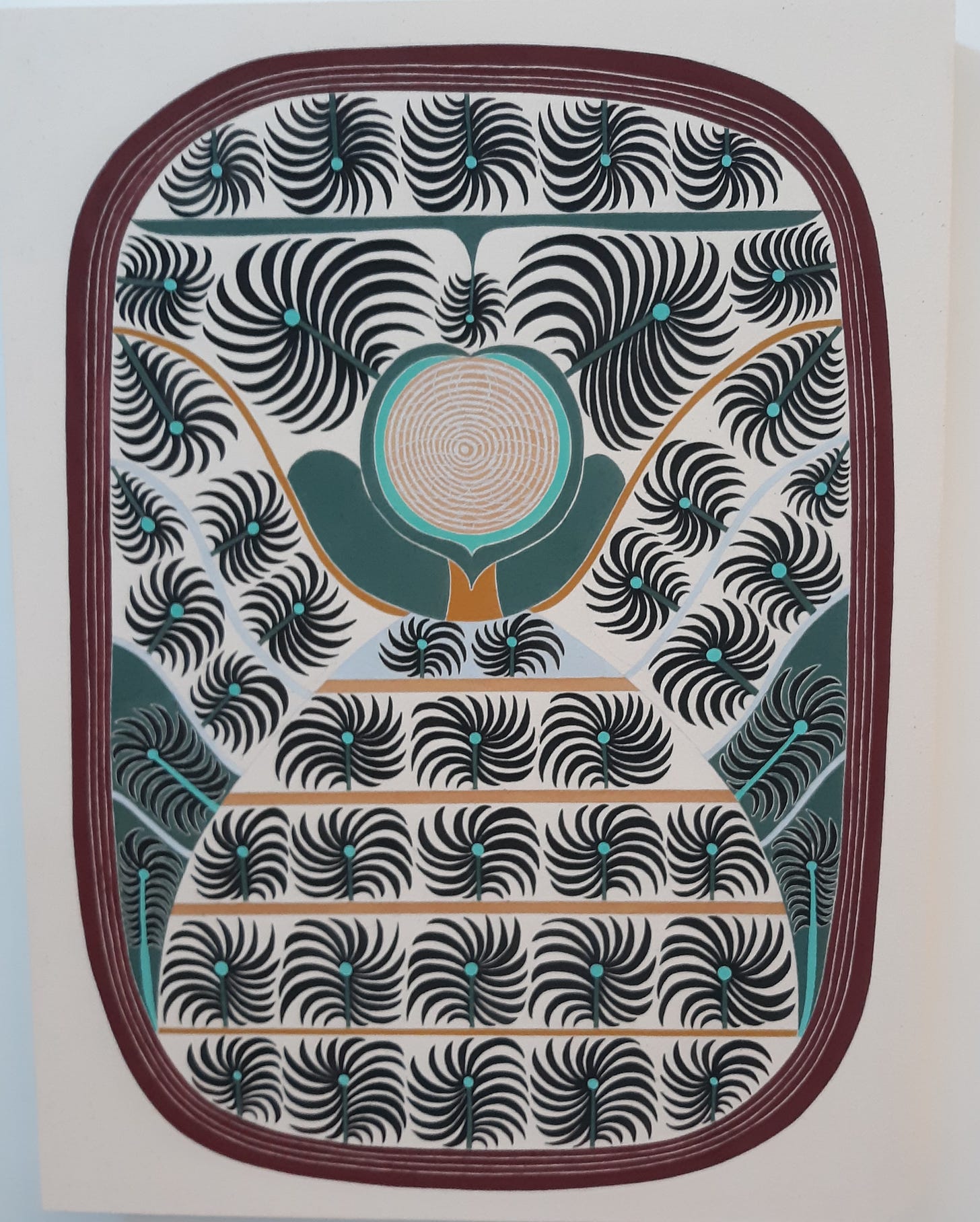

Matt Messinger is an artist I know personally. From where I sit, I can look at a painting/collage that he made. I remember first seeing his work at the 2011 Big Show at Lawndale. He has been around in the Houston art scene but has never gotten the recognition that I think he deserves. For this exhibit, Foltz Fine Art gave him his own room within the gallery.

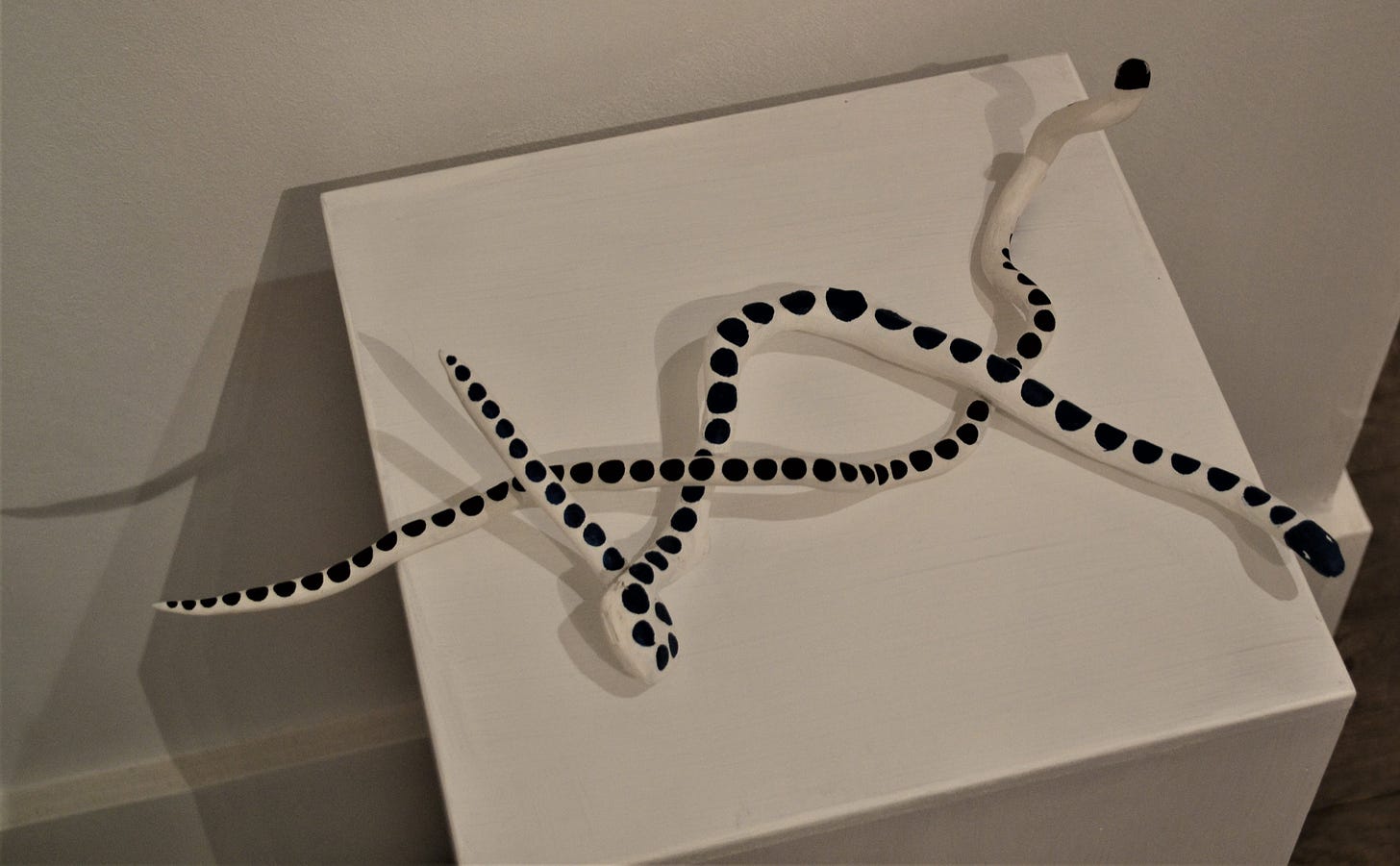

Messnger uses all the space in this little room to show his art. Imagine having the Serpent Rug on the floor of your home. Would you ever walk on it?

The first work I saw by Messinger seemed to reference quite old pop culture (the piece I own is a silhouette of a Fleischer Brothers’ Popeye, a cartoon series that was produced in the 1930s). But nowadays, Messinger seems to produce mostly animals and mythological beasts, in a way that suggests totemic use.

OK, I suspect that Theodore is not a totemic spirit animal. I’m guessing he is just a house cat. \

In addition to these works on paper and paintings, Messinger also produces three-dimensional work, often assemblage based.

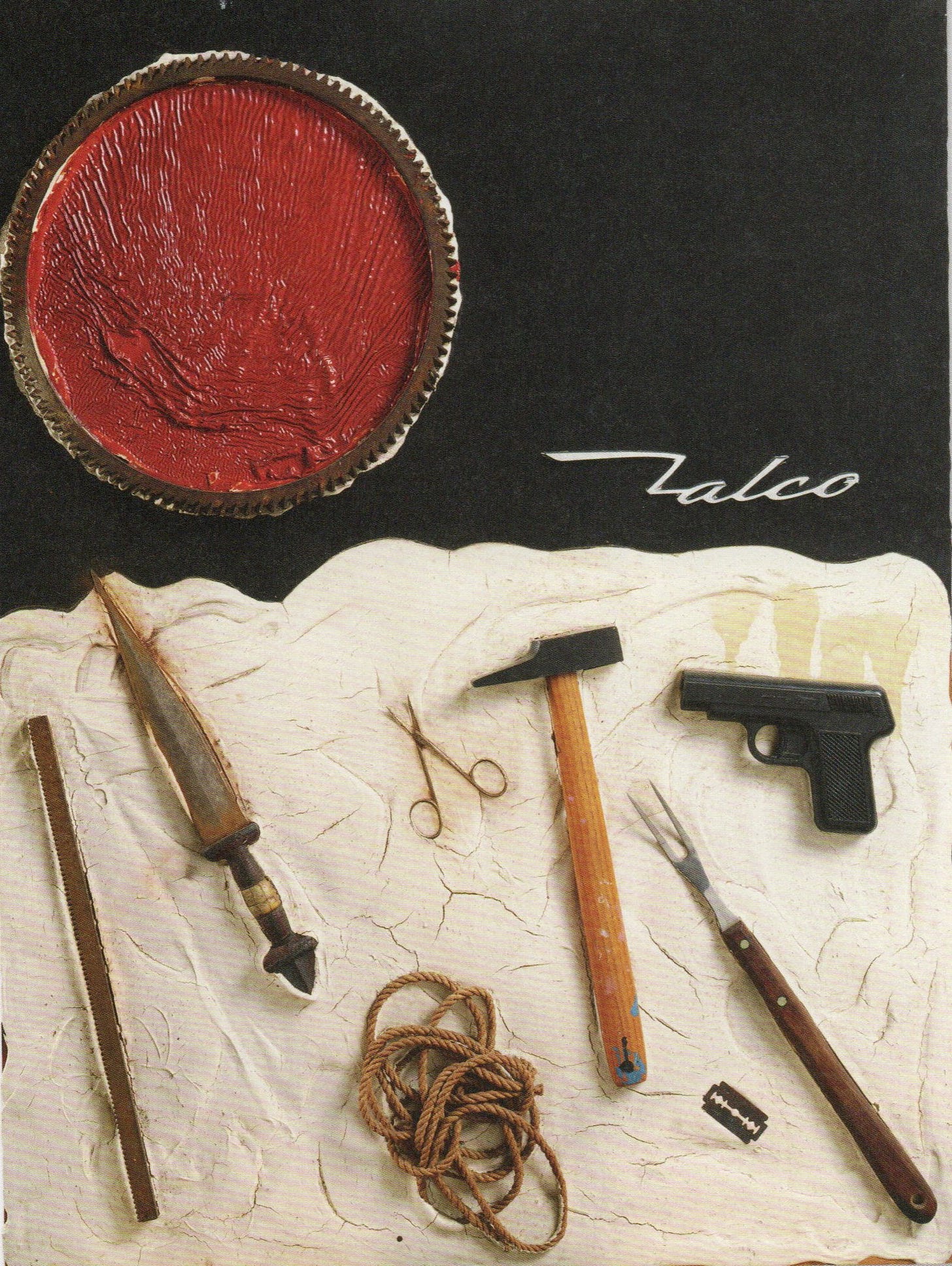

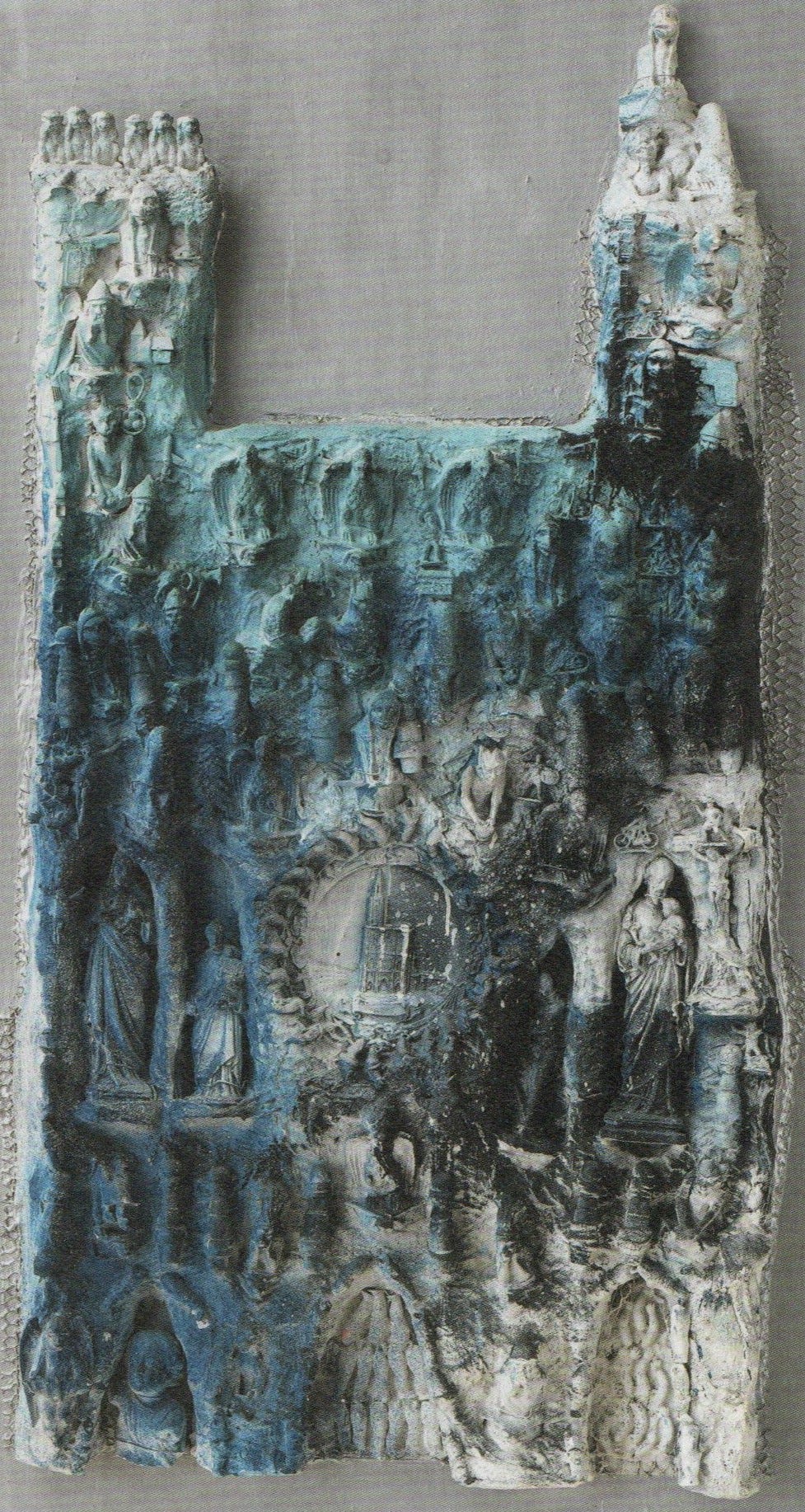

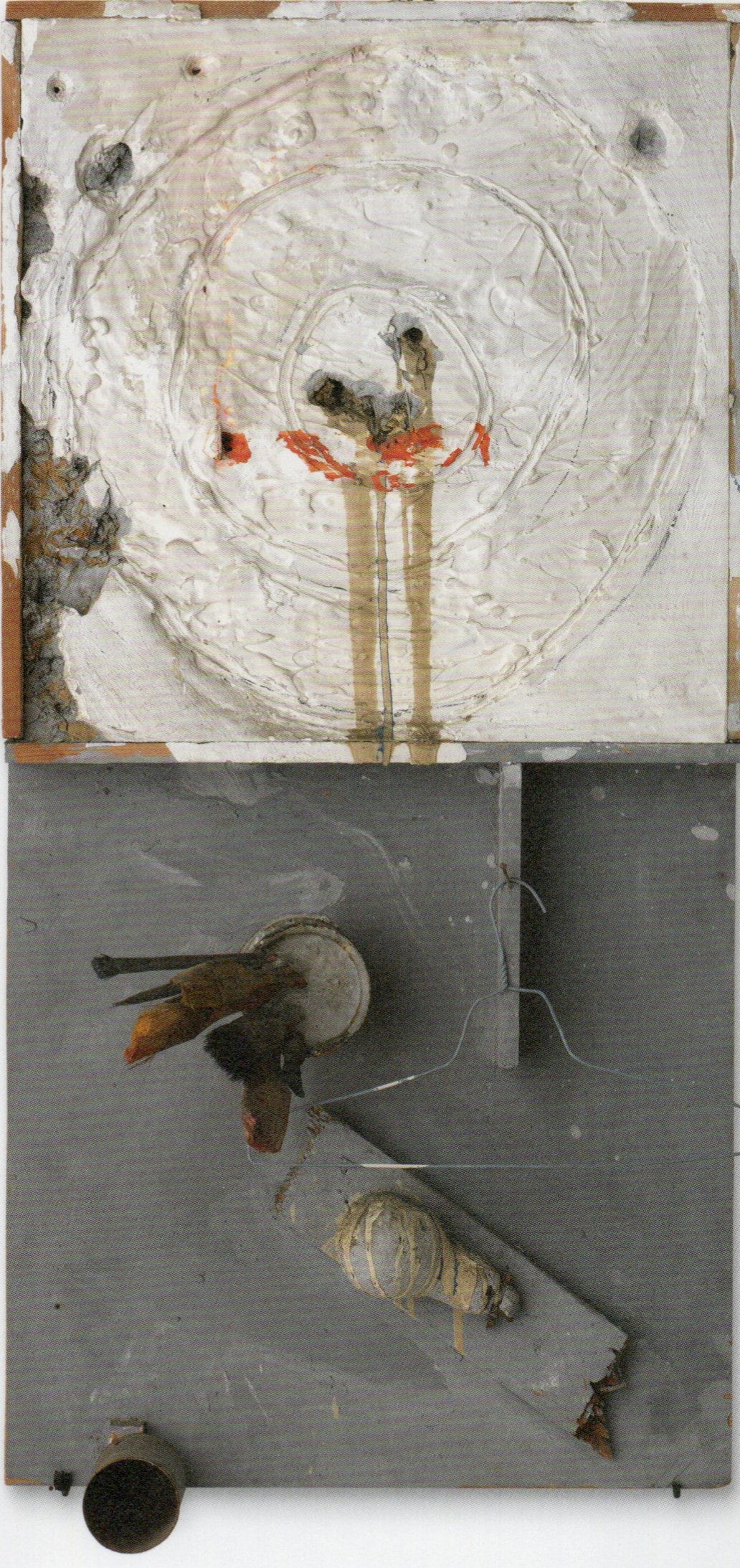

After I visited Foltz Fine Art, I went over to the Menil Museum to check out Niki de Saint Phalle in the 1960s. Niki de Saint Phalle was one of the artists in Nouveau réalisme movement in France that started in 1960 which included such artists as Yves Klein, Arman, César, Mimmo Rotella, and Christo. It is often seen as the French version of Pop Art, though with Yves Klein and Christo, it doesn’t feel all that Pop. And really, the work by Niki de Saint Phalle in this show seems, at best, tangentially related to Pop.

One thing that was in the air at the time all over the Western World was assemblage. I was reminded of Robert Rauschenberg looking at Tu est moi.

One series of works she did in the early 60s were called Tirs. “Tir” is French for “shot”. Saint Phalle would build plaster constructions with bags of paint on them then shoot them with a rifle wo let the paint run down over the painting. She often invited other artists to participate in the shooting part. In this example, she takes one of the most famous images that Jasper Johns painted repeatedly, the target, and used it as an actual target. She made four bullseyes as well as a large number of bad shots. The lightbulb and can with paintbrushes directly refer to specific works by Johns. It seems perfect that Saint Phalle took Johns idea of a target for its intended purpose. Johns took something that had no aesthetic value—a target—and turned it into art. Saint Phalle returns it to the world by shooting it.

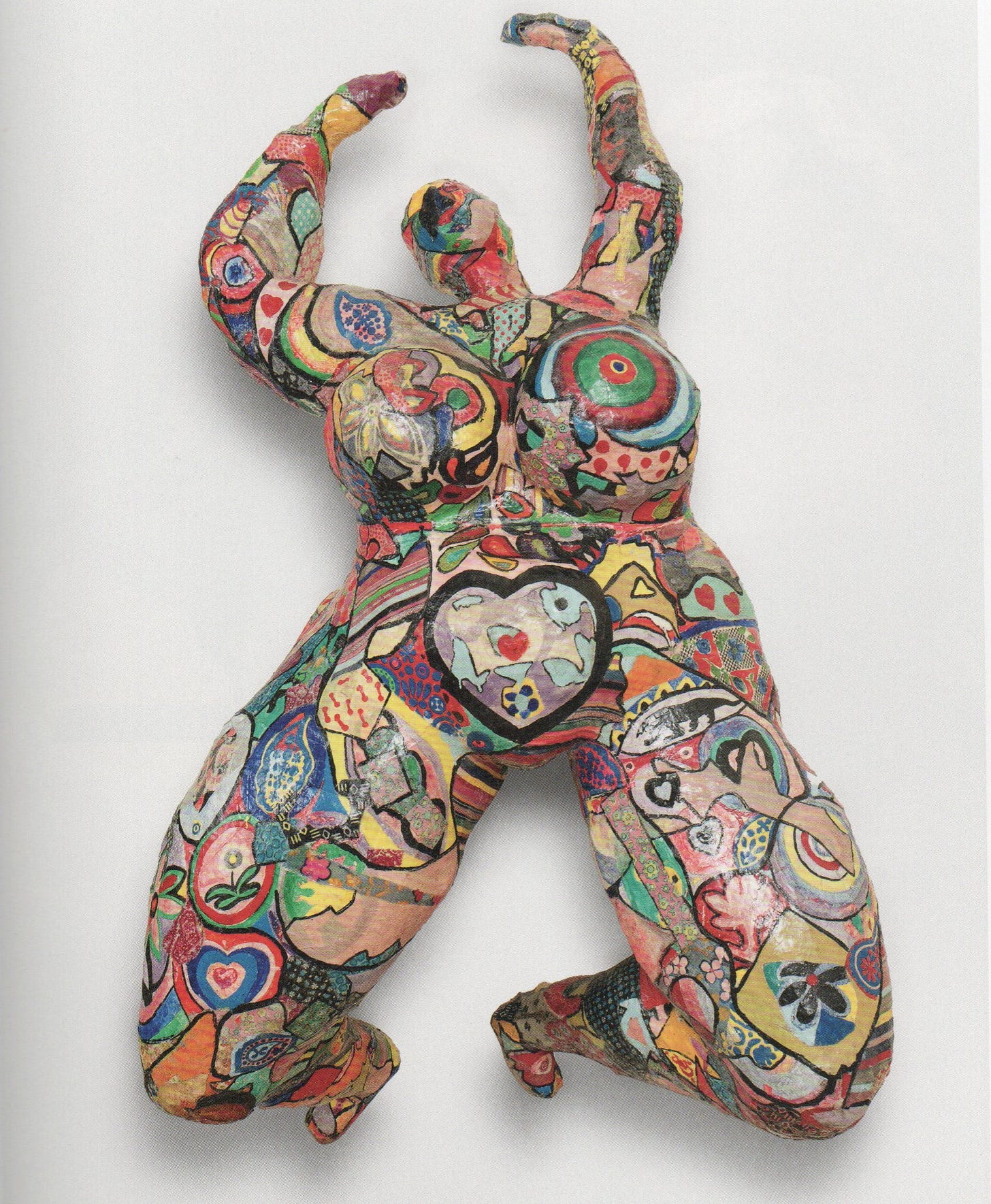

Lili ou Tony is an examples of Saint Phalle’s series of giant, colorful female figures called “Nanas.” She started doing Nanas in the mid 1960s. Perhaps the most famous Nana was Hon, created in 1966 in the Moderna Museet de Stockholm. Here the Nana was gigantic, on her back, with her legs spread, and an entrance at Hon’s vagina that visitors could enter. I’m curious to know what was inside Hon. Unfortunately, they did not attempt to reproduce Hon for this exhibit.

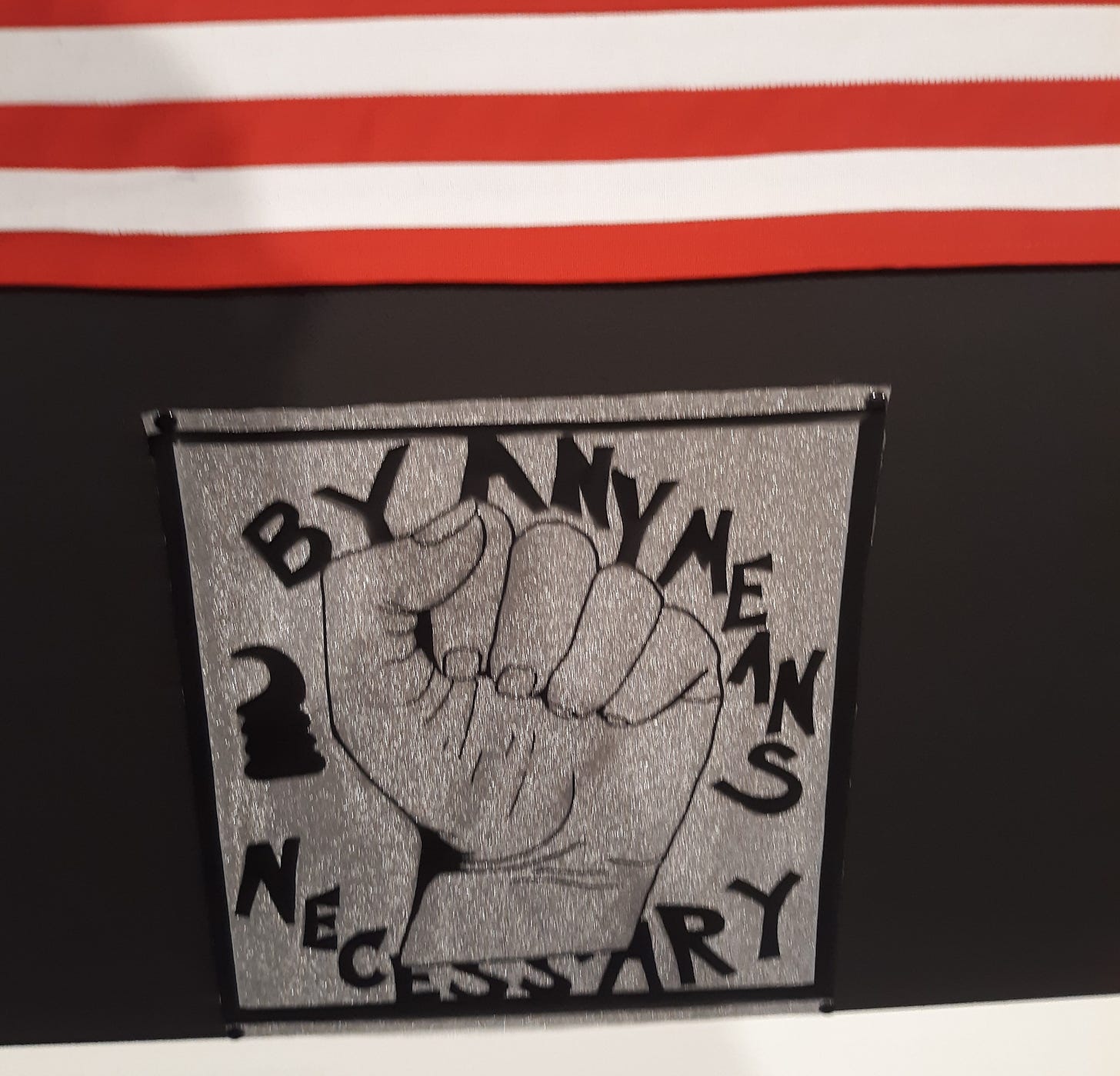

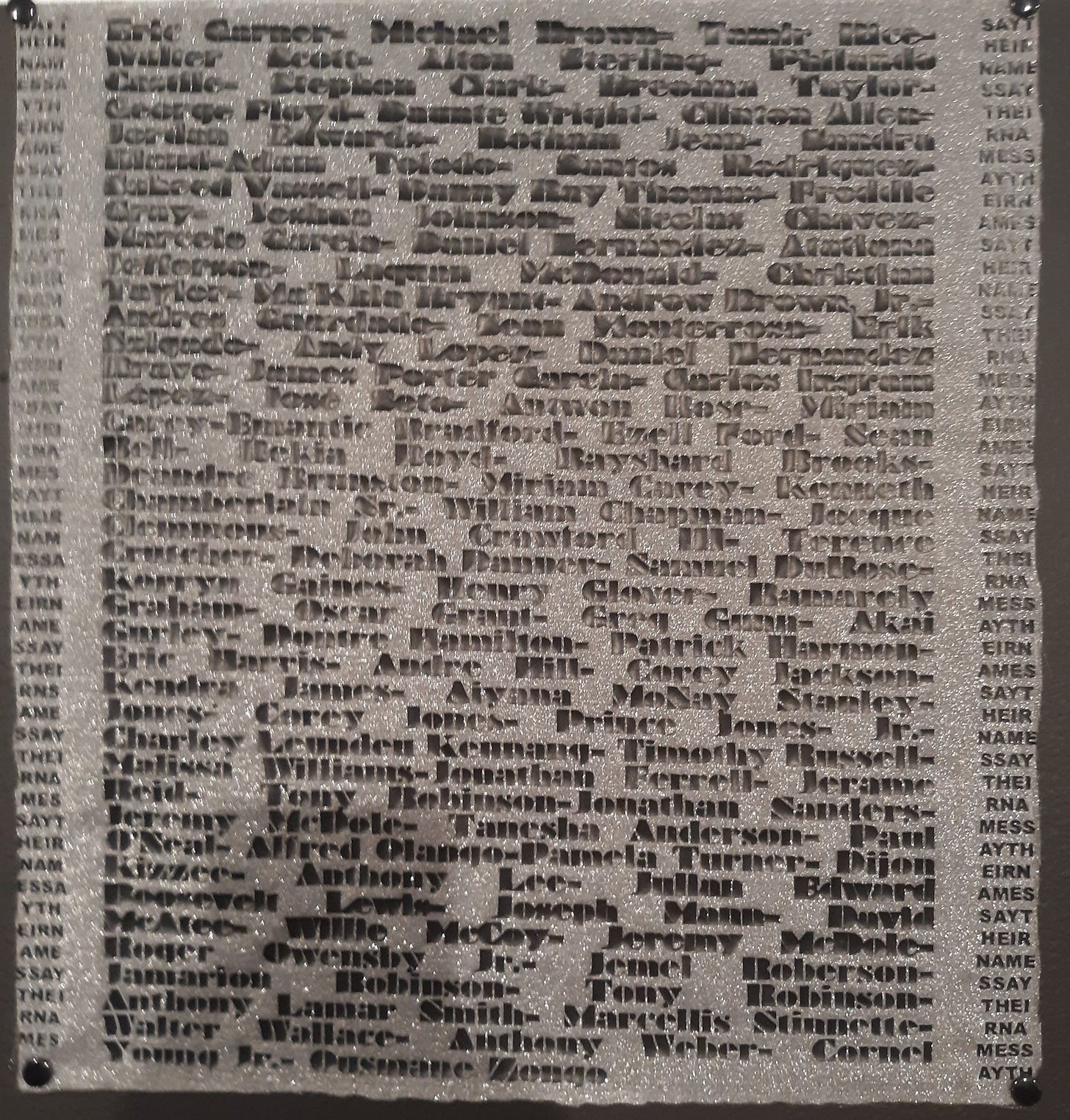

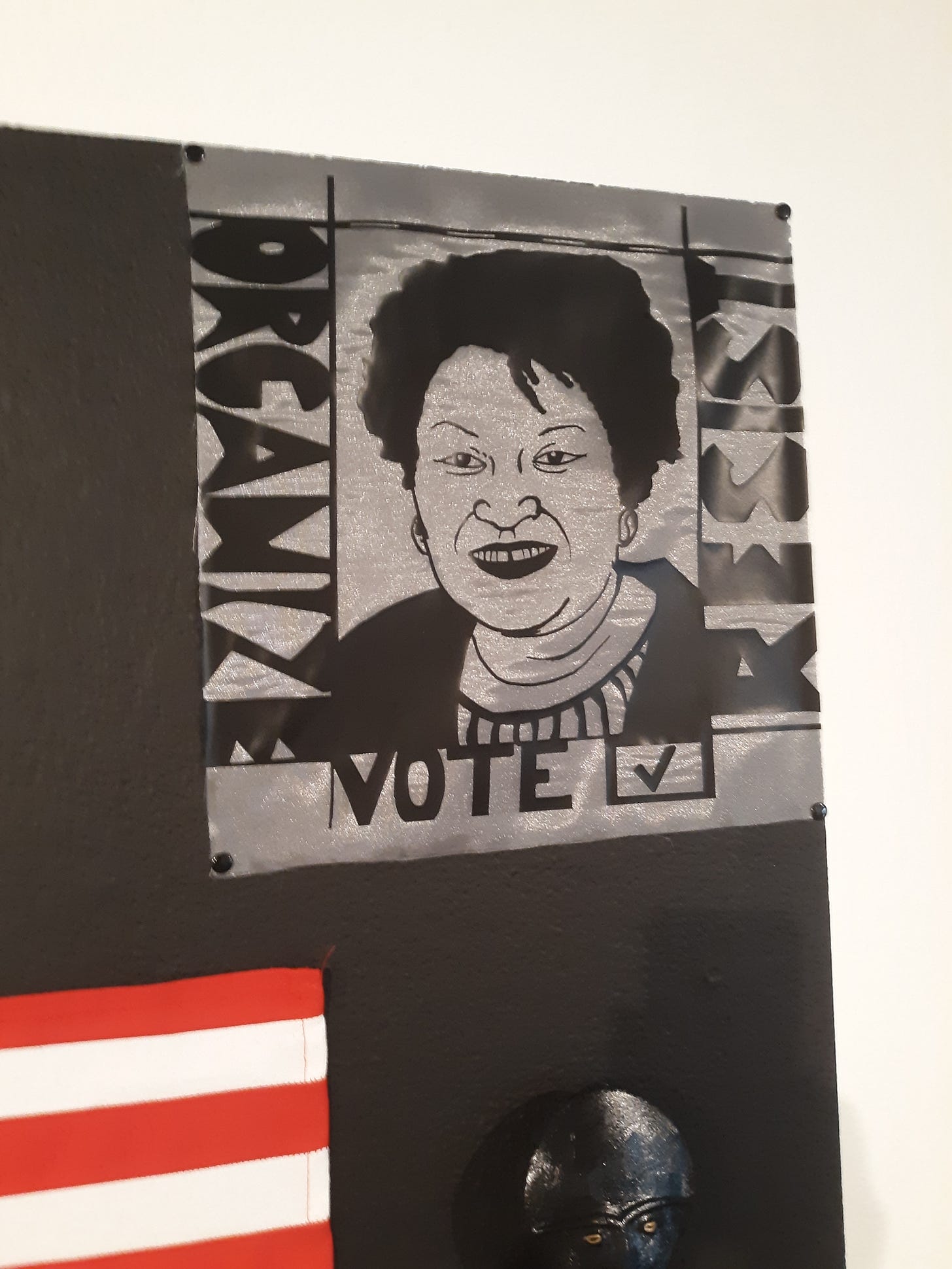

Vicki Meek is the 2021 Texas Artist of the Year at the Art League Houston. Every year they pick an artist (or a collective, as when Havel & Ruck were honored in 2009) for the honor. I don’t know all that much about Meeks. I saw an exhibit she curated at Project Row Houses a few years ago, Life Path 5: Action/Restlessness, back in 2009. But “curated” is the wrong word. Meek collaborated with all the artists on their installations. But aside from that one exhibit, I haven’t seen much of her installation-based artwork. One cool thing about the Texas Artist of the Year exhibits is that the Art League publishes a small monograph about the selected artist. So now I have a book about Meek to catch up on her work. For the exhibit, there are several large works, some of which are wall art but closer to installation in their polyvalence. For instance, Elizabeth Catlett Political Prints & Sculptures Reimagined features not only a central image of a stretched out American flag, it features also African sculptures on two small shelves on either side of the flag, with reimagined political posters above and below the flag.

And what makes it even more installation-like is that it faces an almost identical piece on the opposite wall. Identical in format, but the surrounding political prints are different.

There are more large installations in the front gallery.

This is a recreation of an older piece. Standing in the background are artists Jake Margolin (left) and Nick Vaughan (right), who were out with their extremely energetic baby. One of the reasons I like these openings is that I get to catch up with old friends. The last time I saw either of these two artists was before COVID, before they had a son to drag along to exhibits.

From the Art League, I drove over to ARC House for a small Catherine Colangelo show. ARC House is a private house built on stilts after Harvey to be relatively flood resistant. They have been hosting art exhibits for several years now.

This exhibit showed mainly older works by Colangelo. A week later, a show of her new work opened at Front Gallery.

And as with many of the exhibits, I got to speak with artists I hadn’t seen in over a year. I saw Catherine Colangelo, of course, but also Tudor Mitroi, who has had an exhibit at ARC House early in 2020, before COVID shut everything down.

Those were the exhibits I visited on Friday, September 10. In Part 2, I look at what was happening on Saturday.

Book Report: I Shock Myself by Beatrice Wood

Today I report on I Shock Myself, a memoir by American ceramicist Beatrice Wood. I'm primarily interested in her for her early friendship with Marcel Duchamp and other early dadaists who made their way to New York during the World War I.

The Houston Fall Art Season, part II

In my first installment, I visited four exhibitions. In this one I shall discuss seven! This was Saturday, September 11--an auspicious anniversary. 20 years ago, 2977 people died of a terrorist attack. Now we get 1400 or so dying every day of a mostly preventable disease. And it is this disease that kept most of us collectively from going out to see art for a year and a half. But now that many of us are vaccinated and masked in public, we can venture some public art viewing. On September 11, I first went to the UH Downtown faculty art exhibit, at the O'Kane Art Gallery on campus. I've seen dozens of great exhibits here over the years, but it has a low profile amongst Houston art spaces.

It takes a second to see the row houses in Floyd Newsum's gouache drawing, Row Houses in Red.

Patricia Hernandez, Pink Edge, 2021, acrylic and oil on clay boardPatricia Hernandez got one of the worst reviews I ever wrote on this blog, back in 2011. But I love these paintings. Slashing and disturbing, with their toothy, partially open mouths.

Patricia Hernandez and I both studied art and art history at Rice, and she subsequently founded Studio One Archive Resource, devoted to preserving local art history, which is of great interest to me. Alas, Studio One Archive Resource is now defunct.

I don't really know Mark Cervenka or his art, but he is the director of the O'Kane Gallery at UHD. I liked this picture because of the silent watcher standing in the ruins of a recently destroyed city. It reminded me of images of Stalingrad, but, alas, there are so many destroyed cities that Cervenka could

have used as a model. (I wonder if he is related to Exene Cervenka.)

Mason Rankin is another artist about whom I know nothing, but looking at his work online, this crushed car is very atypical. His website shows him to be a photographer and teacher of photography. But let artists work outside their comfort zones!. I am curious--did he crush the car himself (like John Chamberlain might have done), or did he find it this way?

Last of all, let's look at one of the pieces Beth Secor exhibited in the show. It's an old piece from 2008, which struck me as a little odd. But one can see her new work now at a solo exhibit at Inman Gallery.

After UH Downtown, I went to a place that is in my neighborhood that I had never visited before (although I've walked by it many times). The African American Library at the Gregory School is part of the Houston Public Library System. What specifically interested me was a small exhibit they were having of artwork from the John L. Nau III Collection of Texas Art. One interesting thing they did here was to show self-taught artists alongside more academically trained artists. In other words, the insiders and the outsiders shared wall space for once. This seems especially necessary when showing the work of African-American artists since for so long, many of the greatest African-American artists were denied the training their white peers got. They weren't outsiders by choice.

Sunday Morning is one of two beautiful Kermit Oliver paintings in the show.

And there are several choice John Biggers pieces. A few more recent pieces are part of the collection, as well.

James Bettison, Domestic Bliss, 1988, lithograph

But as I mentioned earlier, what makes this exhibit really special is the inclusion of so-called "outsider" artists as the equals of the trained artists.

Rev. Johnnie Swearingen, Cotton Picking, 1976, oil on masonite

The Reverend Johnnie Swearingen was born in Brehnam. Texas, in 1908 and became interested in painting around 1950. The way these things work is that after some time working totally outside the knowledge of the "art world", and artist like Swearingen gets discovered. These discovery stories are often quite fascinating, but what they suggest is that many Johnnie Swearingens of the world never got discovered and their work remains unknown.

Frank Albert Jones, Grandpa's Devil House, 1952, colored pencil on paper

Frank Albert Jones was a prisoner in the Texas State Prison system. He saw ghost, devils and "haints" that he drew as confined in devil houses. I wonder if that reflected the circumstance he found himself in, where criminals were confined in their cells. Here is a detail from the drawing above:

Frank Albert Jones, Grandpa's Devil House detail, 1952, colored pencil on paperNext I went over to the galleries on Colquitt, which seem to be slowly disappearing. Soon the beautiful Achitectonica building that has long housed art galleries will be the home of nothing but fancy marble floor-covering stores (which would be a case of replacing one type of high-end bourgeois retail establish with another, I guess.) First I went to Heidi Vaughan Fine Art for a solo show by Patrick McGrath Muniz. No one can deny his skill as a painter, but I was unmoved by them.

Diasporamus, painted soon after Hurricane Harvey, may stir a few terrifying memories for Houstonians.

Across the alleyway from Heidi Vaughn Fine Art is Gray Contemporary, which was showing two exhibits; a solo exhibit by Matthew Woodward and a small group exhibit in the back gallery. Matthew Woodward's work was some of my favorite that I saw this weekend.

His work has a kind of simple idea. Find some attractive, old-fashioned architectural detail and draw it very large on paper. But because he'd drawing it white on slashing black-painted underpainting, on rough brown paper that is often torn, it makes the idea of a ruin stand out. As artworks, they remind me a little of English "Follies", gardens from the 17th and 18th century that were designed to look like ruins. I can't say exactly what I liked so much about these, but I was moved by them.

The back gallery at Gray was filled with tiny sculptures, each one a only a few inches in any dimension. It was a nice little collection.

A quick stroll down the street and I was at Moody Gallery, where one of their best known artists James Drake was exhibiting a huge drawing (along with a lot of preparatory drawings).

James Drake, Can We Know the Sound of Forgiveness, 2021, charcoal on paper mounted on canvas

I've greatly enjoyed James Drake's artwork for years, but this one doesn't really move me.

In the back room, they had a small group show up.

Terry Allen, Rage, 1995, etching, aquatint, collageMelissa Miller, Forest Fire, 2019, oil on canvas

I couldn't photograph either of these pictures head on because gallerist Betty Moody was in the middle of the room on a ladder adjusting the track lighting.

I next went to Hooks-Epstein Gallery. One of the biggest changes of the COVID times was the death of Geri Hooks. She cofounded the gallery in 1969, making it one of the longest lived galleries in Houston. (Texas Gallery and Moody Gallery are both up there in longevity, but I don't know which of the three is the oldest)> Hooks died in June, and I have been wondering what the future holds for the gallery. I don't know who owns it now. But it is still in business.

The currently have a small group show up. A bunch of old favorites of mine have their work on display.

Mark Greenwalt was the subject of a post in the first year of The Great God Pan Is Dead, just over 12 years ago.

Mayuko Ono Gray, Pulsating Still Life--Composition in Green, 2021, graphite on paper

I appreciate the irony of naming a graphite drawing "Composition in Green." It was also intersting to see a Mayuko Ono Gray piece without Japanese characters woven into the composition. Here she goes for a Dutch still-life with bubbles added.

Clara Hoag, Sailor, 2021, ceramic

Clara Hoag was in the gallery that day. I asked her about the black coloring on the feet, whether it was a glaze applied before firing or paint applied afterwards. The answer was neither. The piece was apparently fired more than once and the pigment around the toes was applied between firings. (All of which is to say that I am ignorant of the techniques of ceramics.)

I've always loved Ann Johnson's practice of printing photographic images on surfaces that normall aren't used to print photographs.

From there, I went over to McClain Gallery where Shane Tolbert was having an opening. I haven't seen Tolbert in years, because he moved away. He currently lives in New Mexico. But he was in Houston for his opening.

My memory of Tolbert's work when he was still in Houston was that is was much more pale than the work on display at McClain. This show was full of bold, brightly colored work.

Shane Tolbert, Rope Thrower, 2021, acrylic on canvasIt was great to talk to Tolbert, and I was happy to see, for the second time that weekend, Tudor Mitroi.

My last stop of the day was the concrete cube at 4411 Montrose, which houses several galleries. Two of the galleries there have been there as long as I have been writing about at in Houston. One location, David Shelton, has been there for a few years, and the other two locations are like cursed restaurant locations. No gallery seems to last long in them. One of these is currently vacant, the other is the location of Foto Relevance. Foto Relevance is a bizarre name for a gallery--the word "relevance" seems particularly out-of-place, all the moreso for the surreal exhibition on display now.

Pelle Cass, Volleyball at Northwestern University, Close, 2018, inkjet print on heavy matte rag paperPelle Cass sets up his camera over a playing field of one kind or another, takes 100s of fotos, then layers the figures and balls over one another using Photoshop.

Pelle Cass, Dartmouth Softball, 2019, inkjet print on heavy matte rag paperNext was Anna Mavromatis at Barbara Davis Gallery. I don't know Mavromatis, even though she is based in Houston, as far as I can determine. For this show, she made monoprints of dresses or even made dresses themselves that were hung from the ceiling.

Anna Mavromatis, Daybreak, 2021, old dictionary pages folded and stitched to form the bodice of a young girl's dress, cyanotypes on coffee filters

The blue and grey come from the means of making this object. The images have to do with the early 20th century struggle to gain the right to vote for women.

Benjamin Edmiston had a solo exhibit at David Shelton Gallery.

Benjamin Edmiston, Sundown, 2021, oil, flashe and wax on linen

What I liked about Benjamin Edmiston's paintings of crooked groups of parallel lines was the way they reminded me of badly stacked books--because that is the environment I live in. These would be good paintings for book-lovers. The paintings are completely abstract, but we humans like to find patterns in randomness. It's why we see images when we look at clouds.

The last gallery I'll mention is Anya Tish, and the show she had was perhaps my favorite of the weekend. It was an exhibit of new pieces by Gabriel Martinez.

Gabriel Martinez, Untitled, 2019, found fabric

As you can see, this is a piece made of fabric scraps assembled and quilted. I have to confess that I own one of Martinez's quilted fabric pieces--the most recent piece of art that I've acquired. Back in January, he sent out an email that he was raffling off a piece of art to raise money for the Houston Food Bank. I decided to take a chance and bought my $50 raffle ticket. And I won! It's a small piece, hanging on my wall right now. And it was nice to see the body of work that this small piece was a part of.

Gabriel Martinez, Channel, 2021, found fabric

This was the second rug-like piece I saw that weekend (the other being Snake by Matt Messinger). If I had either one of them, I would never walk on them.

Gabriel Martinez, Untitled, 2019, found fabric

Martinez was at the opening and we were able to have a good discussion about this body of work. When they are described at "found fabric", that is a literal description of Martinez' process. All the pieces of cloth he used were from pieces of clothing he found discarded on the street. It's weird, but if you walk around inside the city, you are almost certain to find a variety of discarded clothes. And every piece has a story that you will never know. Martinez would pick them up, bring them home, and launder them. Then he cuts them up into scraps and produces these quilts.

We talked at first about assemblage art: Robert Rauschenberg, Wallace Berman, and George Herms. Martinez had been at a residency with Herms and the two bonded. Herms is 86 years old now, and his assemblage work was produced using detritus. So Martinez is a contemporary exemplar of assemblage. But Martinez made a point to emphasize the quilting part of the work. He told me that there is a tradition of quilting in his family. Martinez is not just continuing a hundred year old artistic tradition, he is also continuing a family craft tradition.

I found these works beautiful and moving. I like them because of how they look, but also because they have a good story.

That was my Fall 2021 art season weekend.

Robert Boyd's Book Report: 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed

Today I report on 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed by Eric H. Cline, a professor of classics and anthropology at George Washington University. The subject here is an event early in human history known as the Bronze Age Collapse, when all of the empires and kingdoms of the Eastern Mediterranean and Near East collapsed more-or-less simultaneously around 1200 B.C.. (Other bronze age civilizations include the early Chinese kingdoms and the Indus River Valley Civilization. China was not really affected by the Bronze Age Collapse and the Indus River Valley Civilization had collapsed earlier.)

The old theory was that a group of sea-faring marauders (called the Sea People) destroyed all the big empires. This theory has taken a beating as archeological techniques have become more sophisticated (especially underwater archeology, seismic archeology, and the study of ancient pollen that indicates when periods of drought occurred) and also as new ancient cities keep being found. In fact, I suspect if there is a new edition of this book in 20 years, some conclusions will have been superceded by new discoveries.

So much of what Cline writes seems possible to write about today. I expect climate change may produce new mega-droughts, new famine, and new migrations. And while it's happening, we might not even be aware that a new dark age is commencing. Cline points out that the Hittites, for example, were not aware that all of their fellow civilizations were collapsing while it was happening.

I recommend the book--Cline is a lively writer and it's useful to have an index and a list of names of the historical figures. But Cline has also done some good lectures online.

Liminal States/Silver #2

I am a material boy. I love to own things, especially if those things were created by artists. But because I was laid off shortly after COVID started, I haven't been spending money on art. (If you're hiring, call me!) But a few days ago, I got a new piece of art, which you can see above, hanging in my grimy apartment. It is a work by Jim Nolan, an old artist friend of mine.

I think I met him when he was giving a brief talk about his work in a Lawndale Big Show about 11 years ago. His work was distinguished then by it's somewhat rough-hewn, craft-less approach. I wish I had a recording of his talk, but I remember that he concluded with a statement like this: "If you keep working on a thing, does it get better?" I'm paraphrasing from memory. It seemed like a strong statement against craft. But nowadays, he is still creating artworks that veer into the conceptual, but he is also doing work as a potter. It seems that he has embraced craft.

I've written about Nolan's work several times over the past few years. And I thought it would be fun to celebrate this new acquisition with a short post about this work.

The whole thing is a wooden construction, including the hand-built black frame. The gray square in the center is wood painted with silvery paint. The holes are neatly cut, and about an inch or two beneath the surface is a mirror.

What is it all about? I have no idea. But Jim has told me that all his art is in dialogue with the work of earlier artists. That feels a little masturbatory, but lets be realistic--except for "outsider artists", every artist is in some way in dialogue with the past. I don't mean to suggest that we have a Harold Bloomian anxiety of influence going on here, but why not?

I don't have an explanation that's better than that, but I'm sure if you buy him a beer, Nolan will tell you something...

Funny Ha-ha AND Funny Strange

I want to write a brief note on Emily Peacock's new exhibit which is up at Lawndale Art & Performance Center through January 15, 2022. The name of the show is die laughing.

I've been following Peacock's work for a long time. The first time I saw her work and was aware of it was in 2011 when she was part of the MFA exhibit at U.H. That was a great class--Francis Giampietro, Britt Ragsdale and Jeremy Deprez were three of the class of 2011, along with Peacock. I've written about Peacock and her work several times over the years, but more than that, I've acquired work by Peacock, supported her film project, had her exhibit in the Pan Art Fair (a satellite to the Texas Contemporary Art Fair in 2012), published her work in the single issue of EXU that I published (still available from from the Pan store), and become friends with the artist. Because of this long-time relationship, I am reluctant to try a full-on piece of criticism about die laughing. But I do want to show off some of the works and maybe comment briefly about some of them.

Fast Burning Type, double-sided video, "every rock my son has ever handed me," nylon fibers, 2021

I love that the list of materials includes "every rock my son has ever handed me." I like that it suggests that the first time that happened, Peacock decided, "I'm going to keep this." And between the time I met her, when she was a student, and now, she has a son! Family has always been a major factor in Peacock's work, and the death of her mother was the catalyst for some powerful work

My Very Own OOF, spray paint on canvas, 2021

Peacock is a funny artist and a funny person. I've heard her do stand-up and she's not bad. She never shies away from humor in her work--she is never afraid that it might make her seem unserious. And Peacock's OOF does directly refer to Ed Ruscha's painting OOF. Another artist who was not afraid to be funny.

Helluva Performance, archival inkjet print mounted to aluminum, 2021

The after years of making photos of the previous and current generation of Peacocks, I guess it's time for the next generation to get some lens time.

Tastes Funny, trophy, fruit roll-up, fruit by the foot and aluminum pedestal. 2021Somehow I doubt that Tastes Funny is archival.

Tastes Funny detail, trophy, fruit roll-up, fruit by the foot and aluminum pedestal. 2021

Funny Bone: I Don't Feel Til It Hurts, plaster cast of the artist's elbow, 2021

Funny Bone: I Don't Feel Til It Hurts detail, plaster cast of the artist's elbow, 2021

Increase the Contrast, Plexiglas, vinyl & two lawn chairs, 2021

When I first encountered Peacock's work, she was strictly a photographer. For some artists, mastery of one medium is at least part of their goal as an artist. But for some, what they want to express requires a certain flexibility. I wonder if specialization is a product the progress--as human knowledge increased, it became more and more difficult to be good at everything. That makes sense in the sciences and in knowledge fields, but I wonder why the arts were dragged along in this movement towards ever-increasing specialization. Peacock may have gotten a degree in photography, but her work, while always including photos, has moved beyond the simple statement: "Emily Peacock is a photographer." Emily Peacock is an artist.

How High the Moon

The 8th Continent is the title of a new artwork by Brazilian artist Clarissa Tossin now on view in the Brochstein Pavilion at Rice University. Some followers of the Houston art scene may recall that Tossin was a Core Fellow from 2010 to 2012. During her time in Houston, she was in two Core Exhibits at the old Glassell school (one of which I wrote about), and in exhibits at Sicardi Gallery and the Houston Center for Photography.

The 8th Continent are a series of tapestries produced with metallic thread on a jacquard machine, a type of loom invented in the 19th century that used punch cards to communicate the design to the machine--it was a precursor in a way to the computing machines of the next century. But the large tapestries are meant to recall those produced during medieval and Renaissance times. These were Veblen goods--they signified the wealth and power of their owners (although they did have a practical purpose--buildings then were drafty and poorly insulated, which tapestries helped). The metallic thread in The 8th Continent also are design to recall the ostentatious wealth display of ancient tapestries.

Clarissa Tossin, The 8th Continent center tapestry, tapestry with metallic thread, 2021The 8th Continent was produced with the cooperation of Rice’s Space Institute and Houston’s Lunar and Planetary Institute. They depict areas on the poles of the moon that are possible sites for future moon missions. It is thought that in some of the shadows of some crater--shadows that are never exposed to the sun--there may be water ice.

Tossin used high-contrast photos as her source material, which make the shadows seem even darker than they might otherwise. The black in the tapestry is especially black, presumably because the sewn surface traps light very well.

So why should these lunar locations be the subject of this modern tapestry? The idea is that because of a 2015 treaty, the Artemis Accords, the USA might be able to mine the moon, particularly to extract water from these dark craters to make rocket fuel from. Why go to the moon to get the water? After all, we have plenty on Earth. But the problem is that it takes a lot of energy to lift rocket fuel away from Earth. A lot of what we're doing when a rocket lifts off is lifting the fuel itself. So if we want to go further than the moon, it would be useful to produce the rocket fuel on the moon and lift off from there. Earth's gravity would still be a drag, but much less so if we were leaving from the moon. So think of these tapestries as trophies of a future colonial possession.

Clarissa Tossin, The 8th Continent left tapestry, tapestry with metallic thread, 2021(As an aside, they fact that we would even consider going to the Moon to get water shows how absurd it is that science fiction films posit aliens coming to Earth to get our water, as in Oblivion (2013). Why would they drop into our gravity well when water is plentiful in the solar system--on the moon, on various other moons like Europa and Ganymede, and in comets.)

I saw this exhibit on September 24, when it was officially installed. The artist was present. I met her and said, "Parabéns," which is Portuguese for "Congratulations." She spoke Portuguese back to me and I was immediately lost--I know it a little, but not enough to converse.

Looking at her CV, it seems that in her most recent works, she is looking at science fiction themes. She has always been interested in Modernity, and what is science fiction but Modernity persisting? (Except for the more dystopian branch of the genre.) But linking this futuristic notion--lunar colonization--with the past--medieval tapestries--places this work is a postmodern space, if I may be allowed to use a term that already is starting to feel antique. Colonizing the Moon won't have the huge cost borne by colonized populations, but there could be conflicts. The Artemis Accord is supposed to prevent that--it defines how far apart different nations' outposts must be from one another. But people are good at finding reasons to fight.

The location of The 8th Continent is interesting. Brochstein Pavilion is not an art gallery, as should be obvious from the photo above. It's a small cafe with spaces for student to get some coffee and study.

It was built in 2007 (long after my student days here in the early '80s), and architects, Thomas Phifer + Partners, made no effort to fit it in with the original Mediterranean design style of Ralph Adams Cram. Trying to contextualize buildings into Cram's original vision is something that Rice has done sporadically since the founding of the university over a century ago, and the result is a mish-mash of architectural styles. The Brochstein Pavillion seems perfect for its purpose, and students seem to enjoy hanging out there. And I suspect that The 8th Continent is just the sort of artwork that will appeal to the nerds of Rice University.

The Artist is an Illegitimate Cosmonaut

by Robert Boyd

Today I reviewed Ilya Kabakov: The Man Who Flew to Space from his Apartment, a short book by Russian art critic Boris Groys. It's a short book--only 60 pages (many of which are full-page illustrations). It's basically an essay on a single piece of art, The Man Who Flew into Space from his Apartment. Ilya Kabakov is one of my favorite artists. He was an "official artist" in the Soviet Union, which means he was a member of the Artists' Union and did work for the state--in his case, for state publishing houses, because he was a children's book illustrator. But he had other things he wanted to express, and developed a double art practice--one official, and one unofficial. But even in his unofficial art, he used the skills he had gained as a book illustrator. This narrative underpinning to his otherwise highly conceptual art is something that Groys reiterates in his book, along with the idea expressed in the title of this post, which is a quote from Groys' text (Kabakov the unofficial artist was a little like a fictional character trying to become a cosmonaut in his own apartment) and the idea of "Cosmism," a Russian philosophical movement with its roots in the 19th century. "Cosmism" is a topic that fascinate Groys--he published a book about it in 2018, and it is the subject of an interesting lecture he gave that can be found on YouTube.

It's Emily Peacock Season

Sometimes an artist shows up in multiple venues at one time. Right now, one can see Beth Secor at UH Downtown and at Inman Gallery. And Emily Peacock has a show at Lawndale and Jonathan Hopson Gallery. I wrote about die laughingat Lawndale and just want to mention lightweight, on view through December 5 at Jonathan Hopson Gallery. I just want to mention two pieces.

Peacock is a photographer, although her artistic practice has evolved into multiple streams—the creation of objects, films, videos, paintings, etc. But she returns to photography here with a series called Bayou Behemoths.

Emily Peacock, Bayou Behemoth, photograph, 2021These photos of kudzu were taken on purple film. They look ominous, like the setting for a horror film or science fiction film on an alien world.

Emily Peacock, Bayou Behemoth, photograph, 2021And this one is like a giant, fuzzy dick protruding from the bayou.

Emily Peacock, Bayou Behemoth, photograph, 2021

The low angles on these make them loom over the viewer. The Bayou Behemoths are wonderfully creepy.

Then there is this piece, which on first glance feels like an inexplicable found object.

Emily Peacock, Flavin Skates: August 4th, 2021

A pair of brightly colored rollerskates on a chrome-plates serving tray. What can they mean?

Emily Peacock, Flavin Skates: August 4th, 2021

There is a story behind them which the artist told me herself at the opening. But she told me that for a certain reason that anyone would understand, “I am not advertising it if you know what I mean.” So I got to hear the story, but you don’t. If you run into Peacock at an opening or just socially, ask her yourself. The story behind the skates is bonkers.

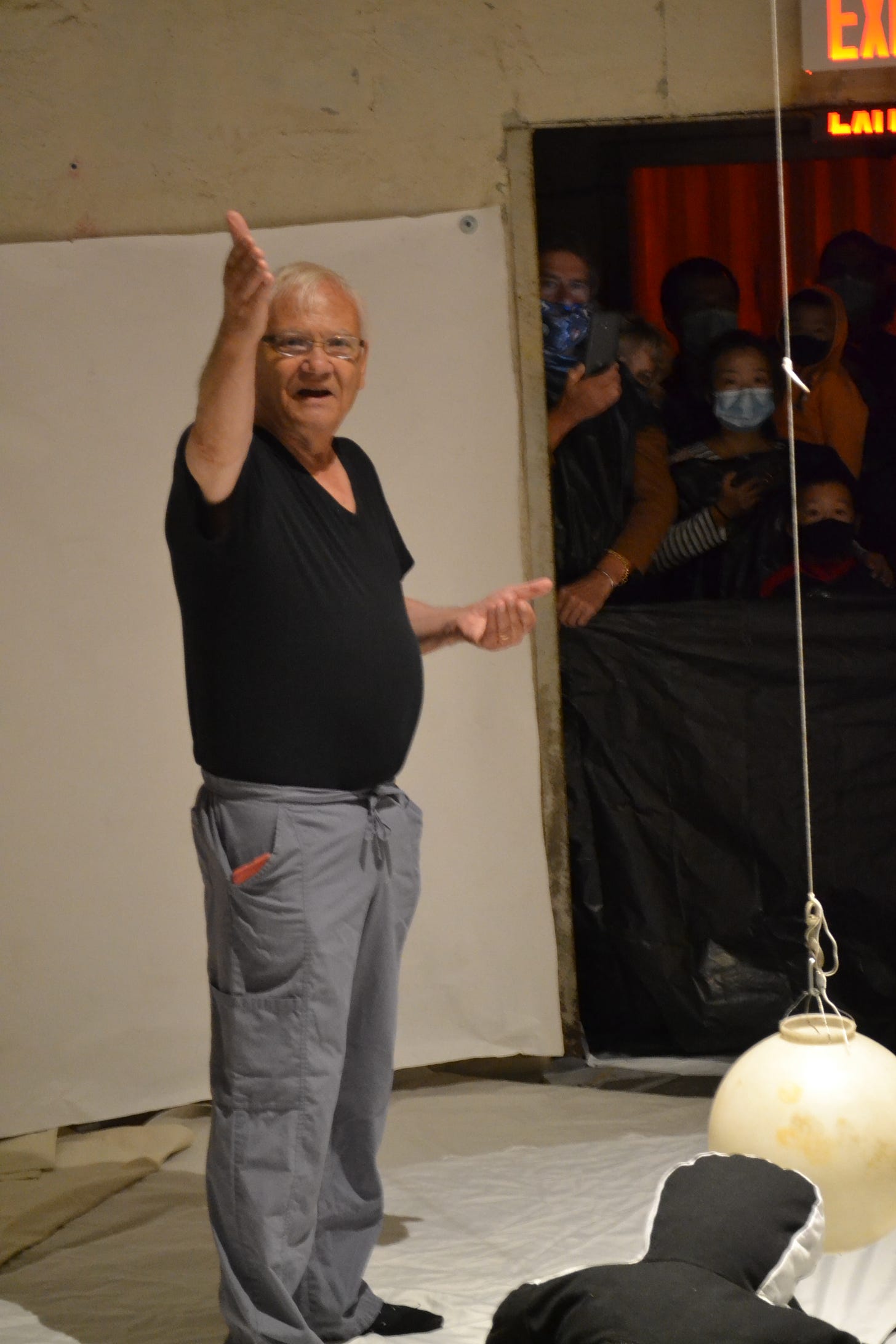

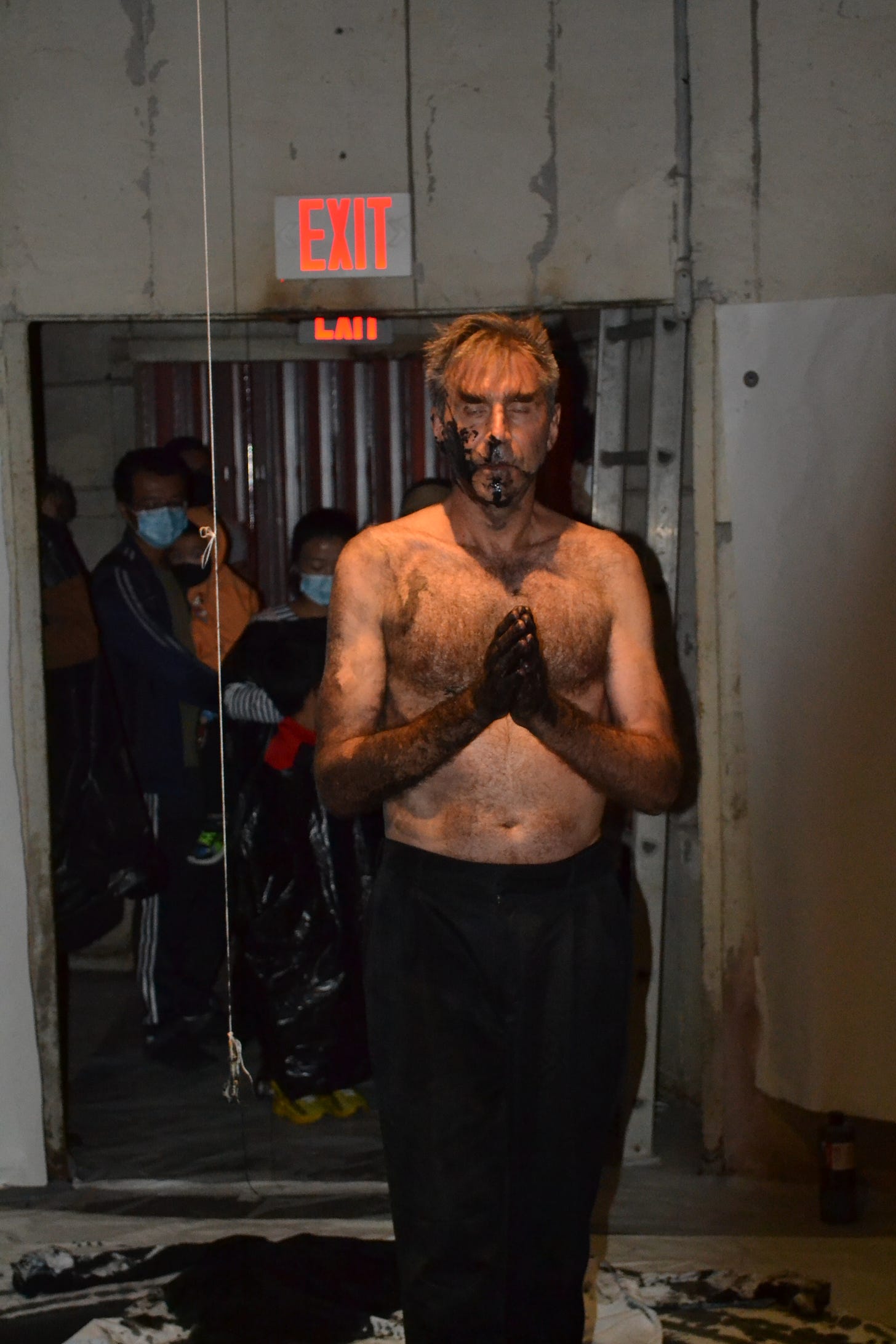

Nestor Topchy at the Silos

On October 16, Nestor Topchy did a performance at the Silos, perhapos the strangest and most awkward visual art venue in Houston. The Silos are actual grain silos, defunct artifacts of industrial agriculture. The Silos has 34 disused silos that it uses to display art. The spaces are a real challenge for artists. They are round, for one thing. Topchy’s performance made use of the round space. Topchy told me the performance did have a name because at the last second before the performance, he changed what he planned to do.

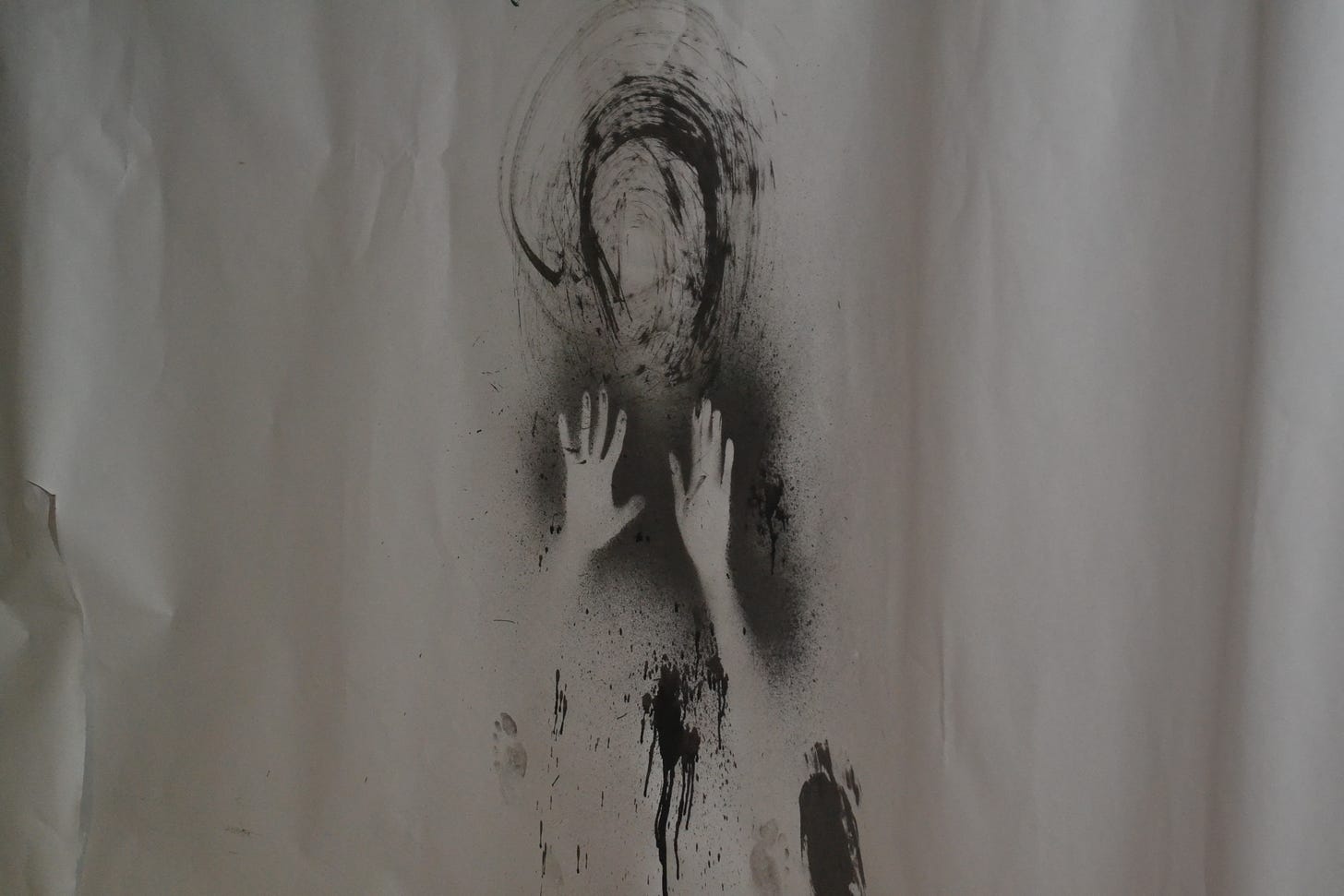

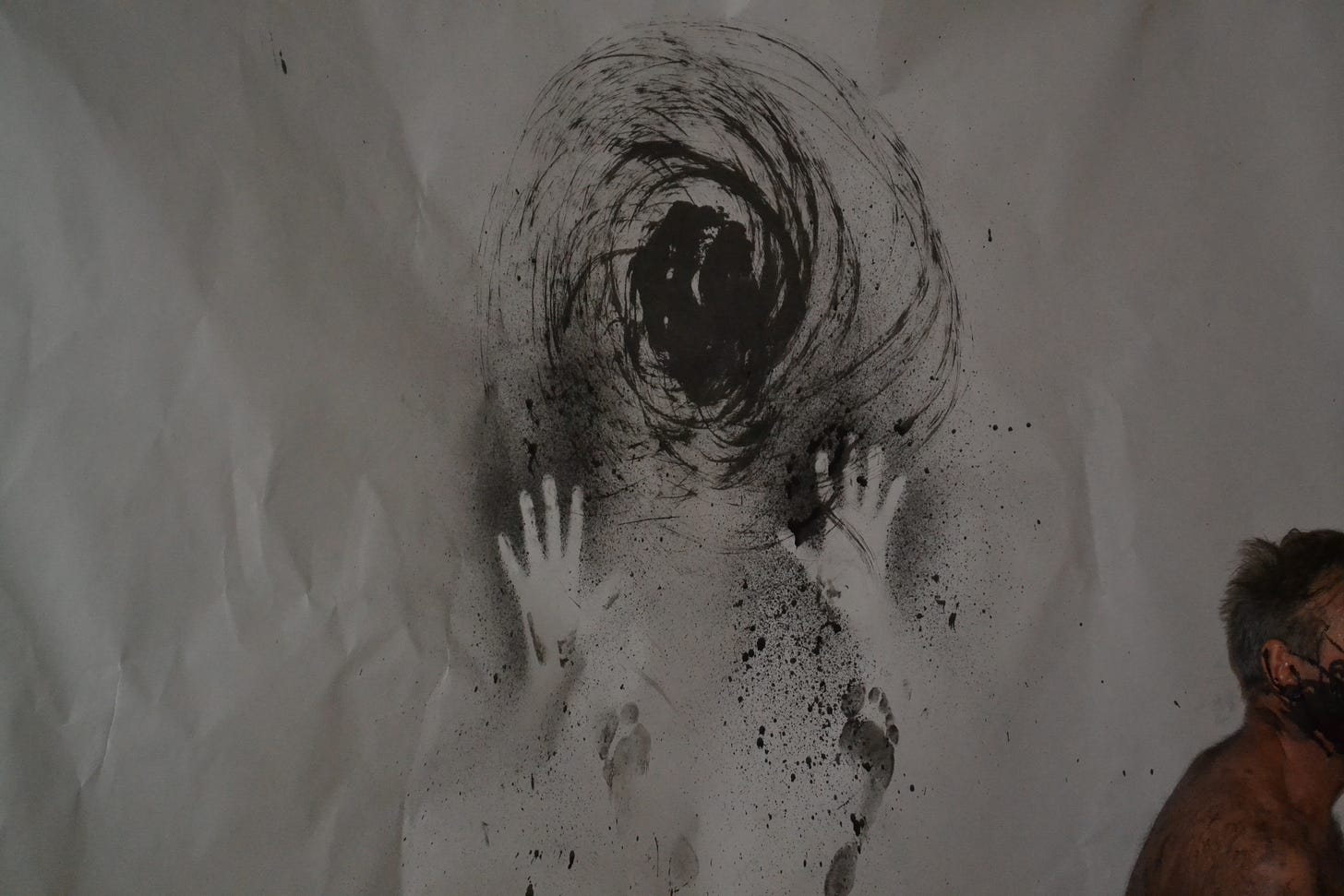

The silo space he was in had a large round platform a couple of inches high, covered by a circular piece of unprimed canvas. The walls were covered with paper. In the center of the canvas was a dummy covered in lack and white fabric. Hanging from the center of the ceiling was a sphere. It appeared to be a light covering.

Before Topchy came out, Volker Eisele, one of the founders of Sculpture Month Houston, came out to talk about the performance. He discussed Topchy’s connection with artist Yves Klein and in particular about International Klein Blue, the pigment that Klein invented and that Topchy has used frequently in the past in his sculptures and performances. But this must have been one of the last minute changes—Topchy did not use IKB.

He used sumi ink in ther performance. He mentioned to me beforehand that he was going to use sumi ink. I aked him if he was going to grind it in person. Ordinarily, sumi ink comes in a compressed, solid block that the artist grinds on a suzuri stone, mixing it with water to get the density of black desired. But it turns out you can buy sumi ink in a bottle, and Topchy had two bottles of the stuff that he poured into the sphere.

Once the sphere was full, Topchy pulled a plug from the bottom of the shere to let the ink leak out. He then set the sphere swinging in a circle.

As it spun around, it produced a fuzzy ink line on the canvas. At first the line was pretty distinct, but as the watery ink soaked into the unprimed canvas, it the line started to fill in.

Topchy knocked the dummy over so it was laying face up. He took off his jacket and lt the ink pour directly onlt the dummy’s face.

He wrestles the dummy, which appeared to be pretty heavy and mashed its ink-covered face into the wall. Then he lay down directly under the sphere.

He let it drip ink into his map. Then he did something on the side of the silo which I couldn’t see from the angle from where I stood. The silos are not really conducive for audiences to view performances within.

He bowed to the audience.

And the performance was over.

Once it was done, one could enter the silo and see what he was doing on the wall. He sprayed the ink from his mouth over his hands to create a negative impression of them.

This form of negative hand stencils is one of humanities earliest forms of art, found in cave paintings all over the world.

This is from Cueva de las Manos in Argentina. They are estimated to be between 13,000 and 9,500 years old.

Browsing Through Zines at El Rincón Social

I can’t remember who told me this or where I read it, but it’s been said that for photographers, the ultimate goal is a book. I think this was said in contrast with other kinds of visual art, where artists might be working towards an exhibition or a museum retrospective or a large public commission. When I heard that assertion, I thought of classic photobooks like The Americans by Robert Frank, Diane Arbus: An Aperture Monograph, or William Eggleston's Guide. But a beautiful hardcover book is not the only way to present your work in a permanent published format. There are many publications that do it, and the most modest of these are zines. They are often self-published, but some very small presses put out tiny photobooks. I think of these publishers as the equivalent of small poetry presses. The small press impulse is to me where the vitality of publishing comes from (whether prose, poetry, art, photos, or comics), occasionally bubbling up to larger publishers and more mainstream means of distribution. What this means is that if you want to experience these publications, you have to seek out the world of alternative press—usually through small-scale book fairs or zine festivals. (Or through the mail directly from the publisher—some I’d recommend are Cattywampus Press, X Artists Books, Deep Vellum, Host Publications, and Ugly Duckling Presse. I’ve bought books that I love from each of these publishers.)

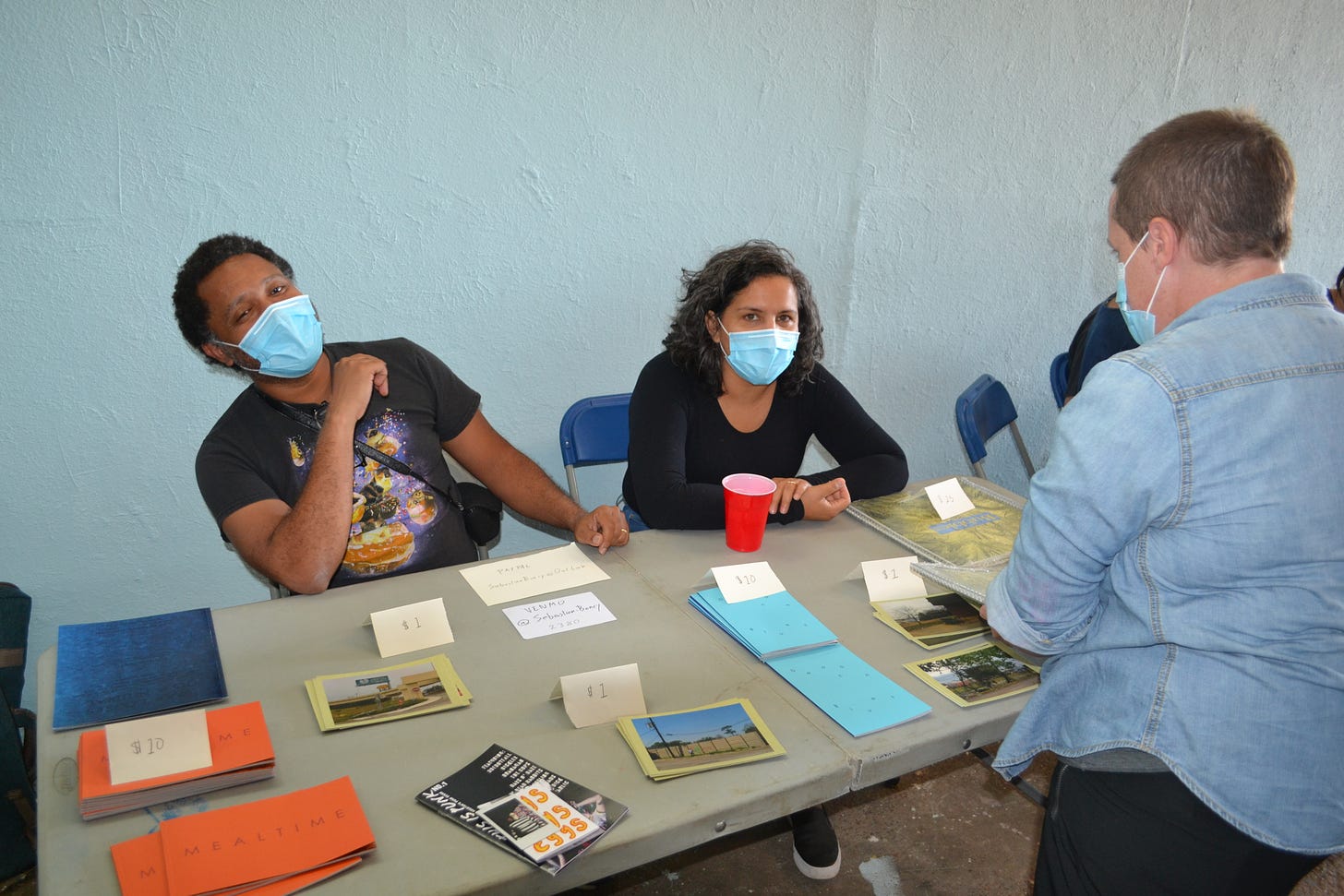

This is why I was at Uncle Bob’s Photo Zine Market on the afternoon of October 16. It was a one-day zine festival held at El Rincón Social, a somewhat obscure art space/artists studio complex just east of downtown Houston. I’ve been there many times before and seen a few spectacular exhibits and installations there. The flyer above was apparently designed by @jadeolantern, about whom I can find nothing online. Nice flyer, though!

El Rincón Social is a large, high-ceiling warehouse space with plenty of room for people to set up tables. They had about 15 exhibitors. It was a small festival, but while I was there, it was lively. In a way, this was a warm up for the bigger zine festival occurring next month: Zine Fest Houston will be held on November 13 at the Orange Show. Uncle Bob’s Photo Zine Market seems to have been one in a series of small zine-oriented events leading up to the big day. That seems like a good way to build some enthusiasm, especially given the fact that Zine Fest had to shut down during 2020 for Covid reasons.

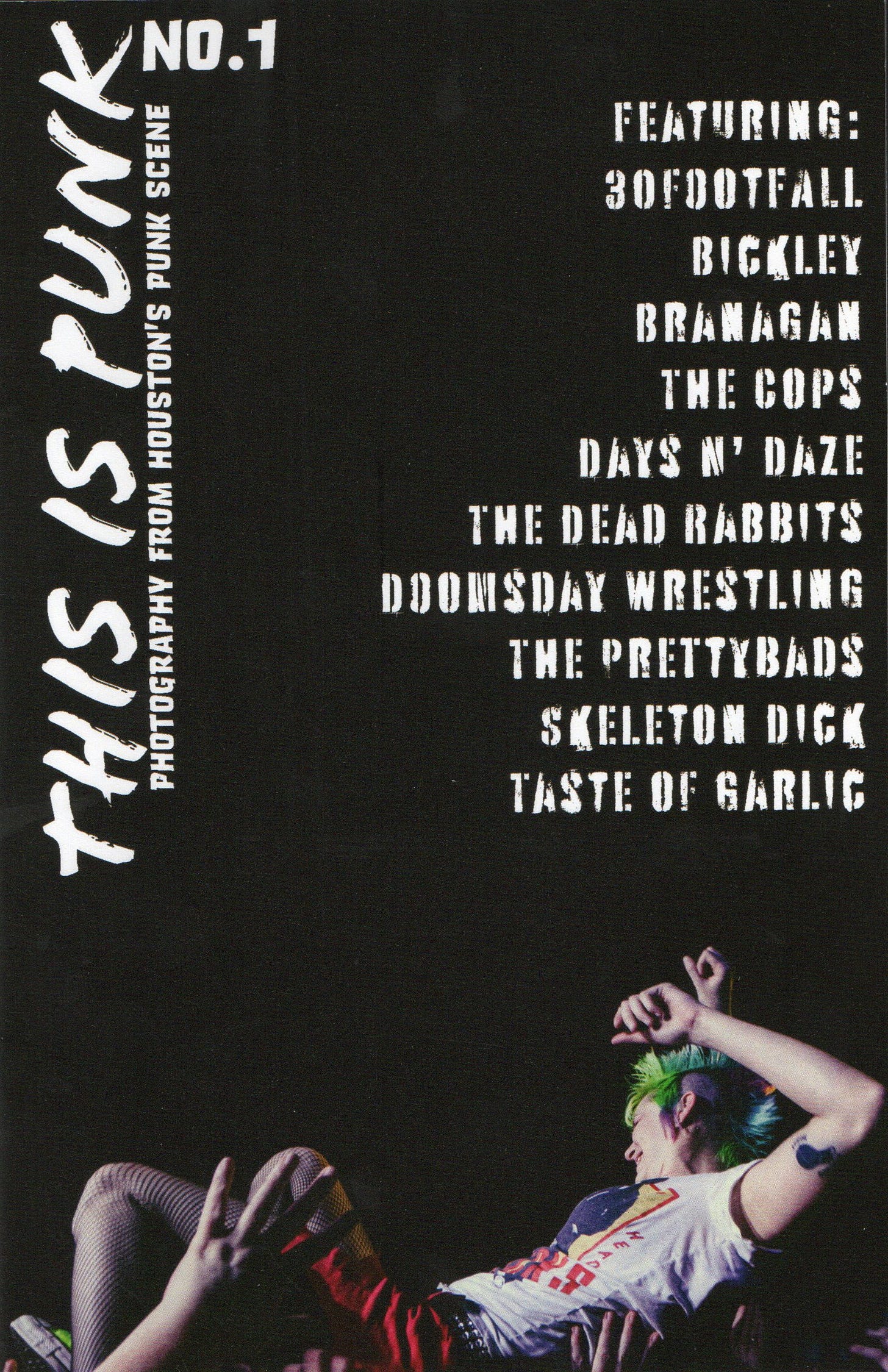

I was there to spend a little money on photo zines. The first I bought was This Is Punk no. 1 by Skyler Payne.

Here is Payne manning his very homey booth. This Is Punk is a documentary photo zine about the late, lamented Fitzgerald’s, a rock and roll club in Houston. Payne has apparently been going to punk rock shows since he was 11, taken by his punk-rock parents.

Payne writes on the first page the following dedication:

In memory of Fitzgerald’s

Where many fans found their favorite bands

Where many bands found their favorite fans

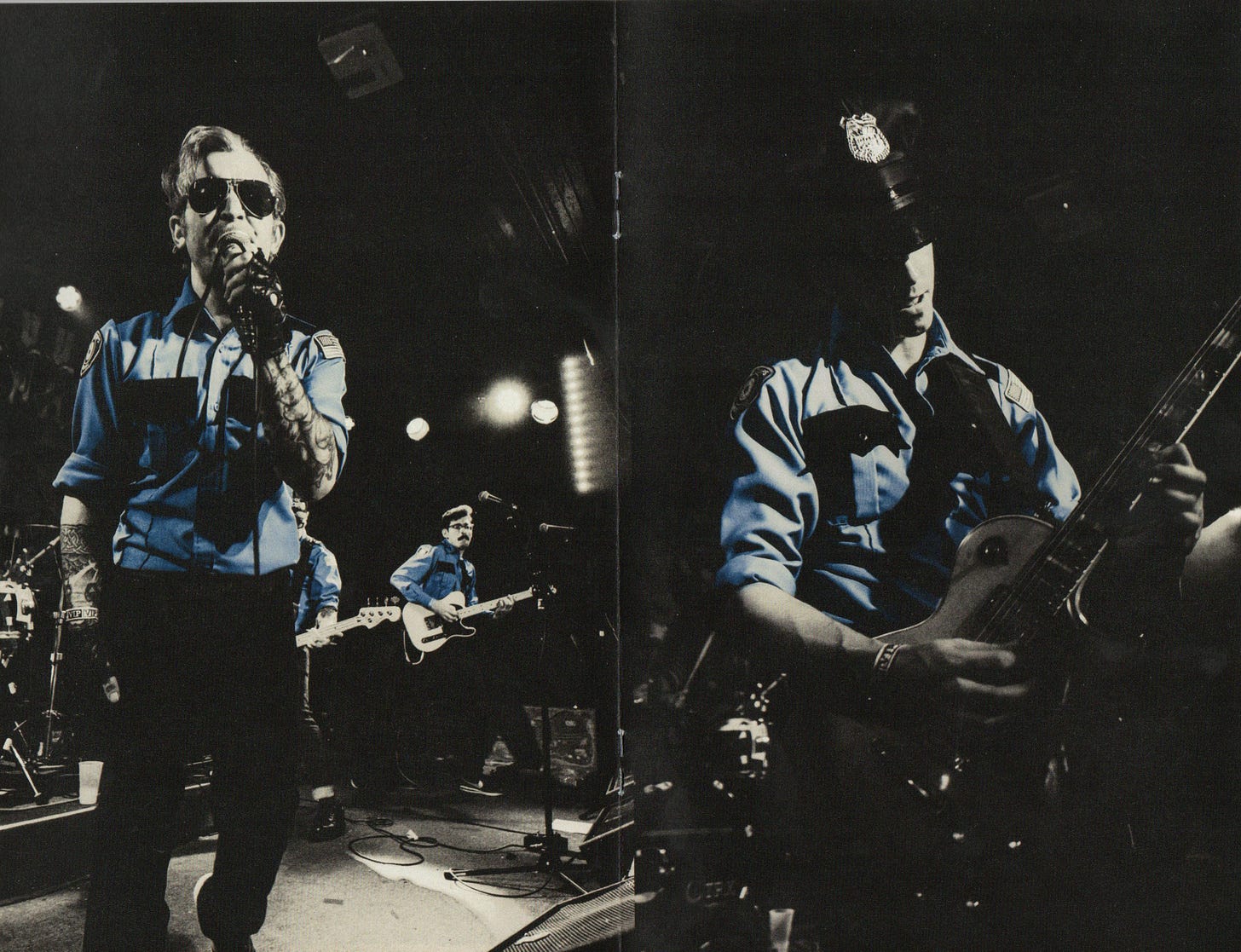

I have no idea who this band was, but I like the way that Payne tinted their shirts. I wonder if they ever play “The Dicks Hate the Police” in homage to early Texas punk rock.

Next I stopped by Jason Dibley’s table where he was displaying his monomaniacal zine series, Broomzine. Photos of brooms. That’s his thing.

He may have a personal identification with brooms, since he is as skinny as a broomstick himself. I’ve bought earlier issues of Broomzine, so I asked what was new. I think this is the newest issue.

That is the front cover on the right and the back cover on the left.

And this is the center spread. The whole publication is 18 pages long (17 of which have full-bleed photos of brooms in situ, and one blank page). In stark contrast to This Is Punk, these do not appear to be photos of something that excites Dibley. The broom is a humble object, and focusing a body of work on brooms, shown without commentary or interpretation, a group of photos that are staggeringly mundane, is weirdly moving.

My next acquisition was Eggs Eggs Eggs, a photo-collage zine printed on a single piece of paper, sliced and folded.. It was a clever bit of origami and had the benefit of not needing staples.

It was created by Anastasia Kirages, one of the organizers of this event and of Zine Fest as a whole.

The basic idea is a fried egg plus a thing. Eggs are funny and incongruous juxtapositions are funny.

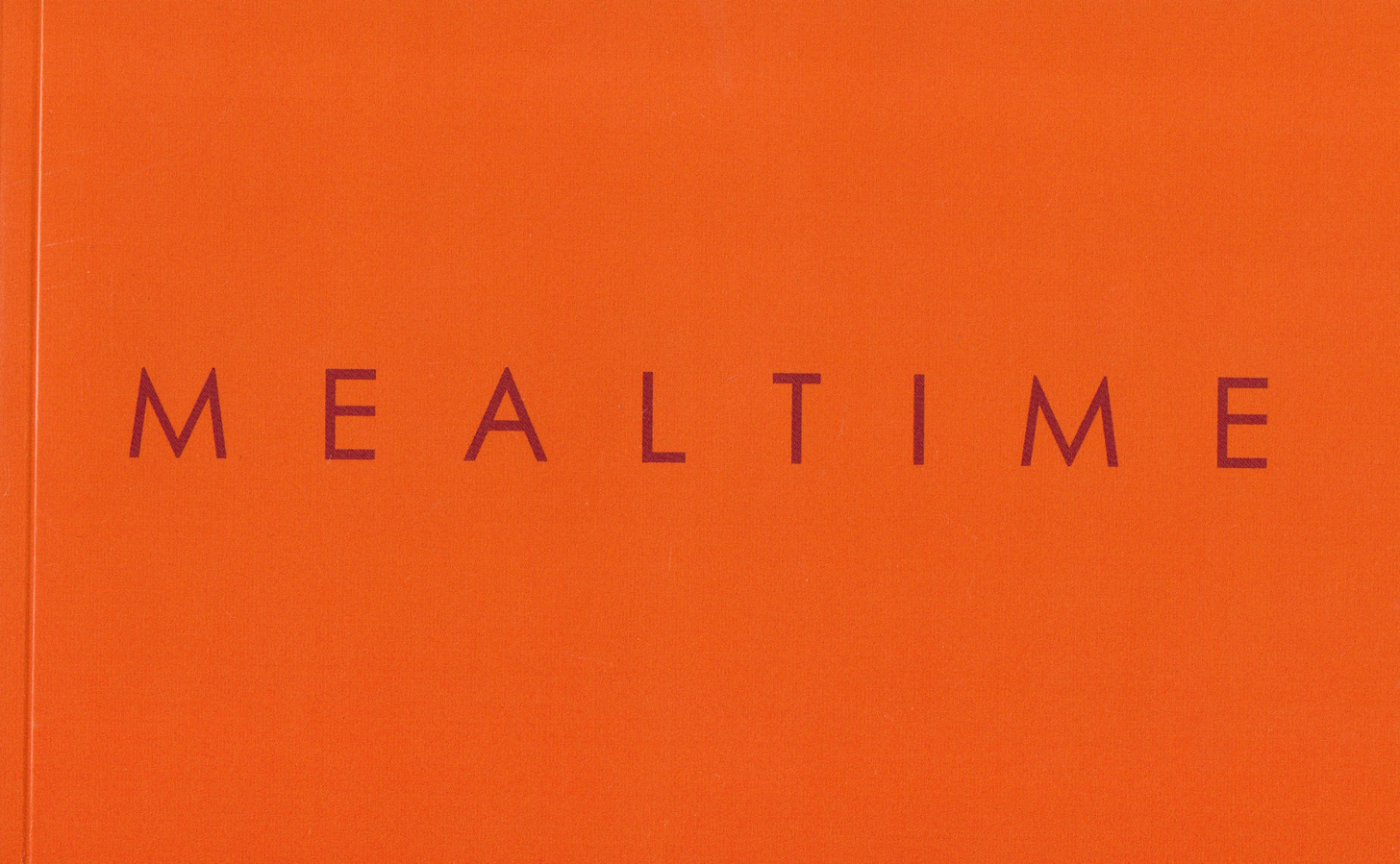

Of all the photo zines I got that day, the most beautifully designed was Mealtime by Sebastien Boncy. He was manning his table with Julie De Vries.

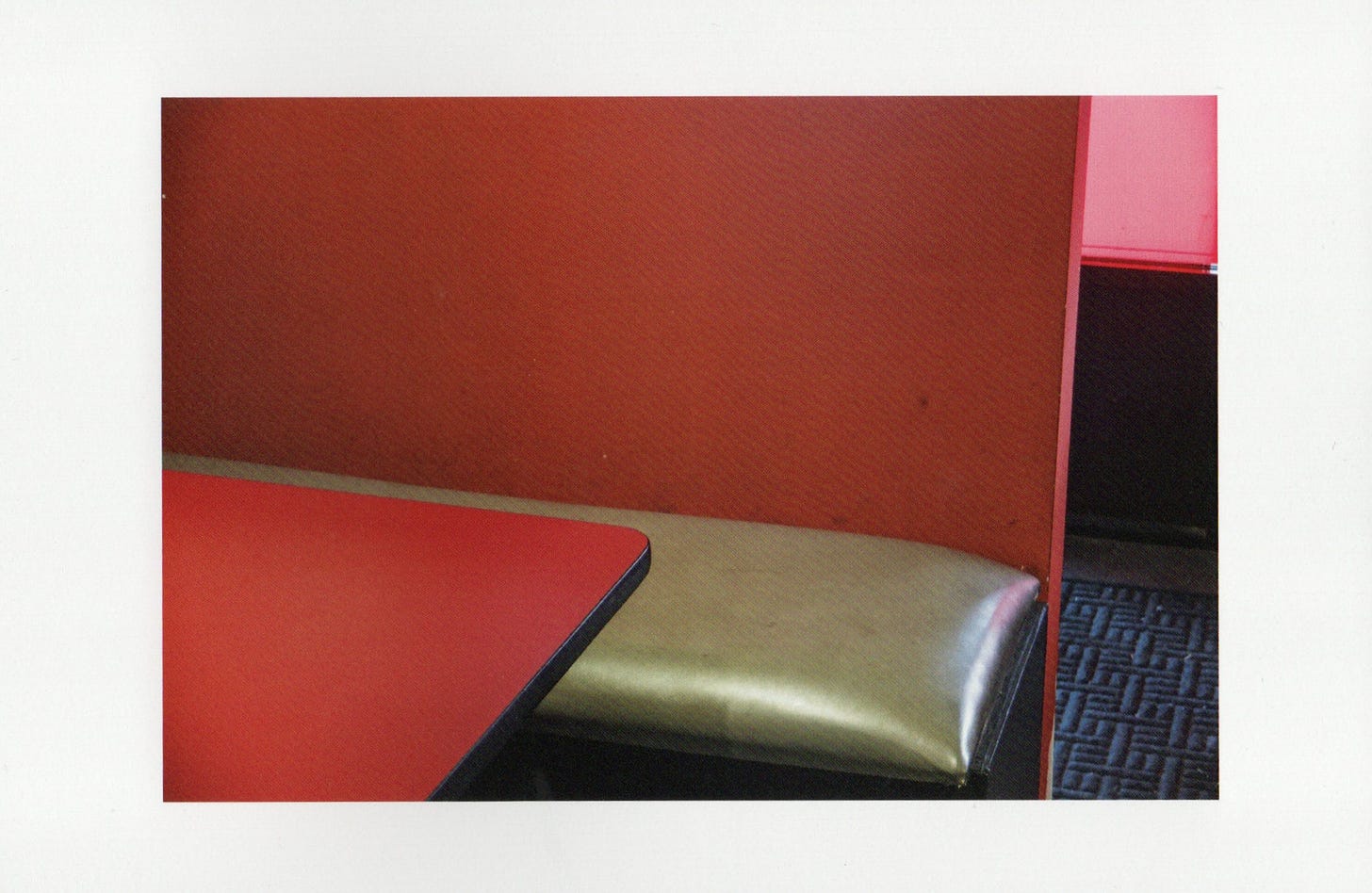

Boncy also specializes in the mundane in his photos, but his eye looks at the world. One rarely sees a person in his photos—just the ghosts of their presence. Mealtime is full of such ghosts.

The remnants of meals past, the places where people eat. All with arresting compositions and colors.

That was Uncle Bob’s Photo Zine Market. In the entrance was a photobooth set up where a woman was taking polaroids for $5. She said they were raising money for a friend, but I don’t know why the friend needed money, or who the friend was, or who the photographer was. But I spent my $5 and got this polaroid.

This tells me that maybe I shouldn’t wear stripes. A valuable lesson that I plan to ignore in the future.

Some Sculpture Month Highlights

Sculpture in inconvenient. It takes up a lot of space and it therefore difficult to collect. There is a funny quote that is variously attributed to Barnett Newman and Ad Reinhardt: “Sculpture is something you bump into when you back up to look at a painting.” As far as I know, Reinhardt never made sculptures, but Newman did. You can see one of his, Broken Obelisk, in Houston in front of the Rothko Chapel. (And at the University of Washington, at Storm King and at the Museum of Modern Art.)

Admittedly, sculpture can be almost anything now, an idea put forth in the classic essay, “Sculpture in the Expanded Field” by Rosalind Krauss, 1979. The anythingness of sculpture was pushed even further in Thomas McEvilley’s book, Sculpture in the Age of Doubt.

Since 2016, every other year (except 2020) has had a “Sculpture Month” here in Houston featuring a month of sculpture exhibitions at multiple venues across Houston. I want to speak briefly about two of the venues and the sculpture within them. One is a venue I mentioned earlier this week where Nestor Topchy did his performance—The Silos. Topchy’s performance was part of Sculpture Month (going with the almost infinitely malleable definition of sculpture). The rest of the silos were also used for a variety of site-specific sculptures.

The first one I came across after entering the space was by Shawn Smith called UnNatural Influence, made of plywood, ink, acrylic paint and silk flowers.

It is a classically Texas subject, a bucking bull, but made out of blocks of wood that imitates pixels. In some ways, this feels like a very traditional sculpture—a single, free-standing object meant to look like a specific thing. Praxiteles would recognize this sculpture, except maybe for the pixelation effect. He would have been most amazed by the artificial lighting effect, which combined with the cave-like interior of the Silos provides a dramatic shadow.

That shadow makes me think of neolithic hunters sitting around a fire in a cave, recounting their hunt for the wild auroch. Aurochs were wild cattle in Europe and Asia that went extinct around 1650. There are depictions of them in cave paintings, including four painted on the walls of the caves at Altamira in Spain. And Altamira is the name of this exhibit, perhaps in honor of cave-like interiors at the Silos.

Susan Budge made an installation that made use of the entire silo she had. Stardust features a central object, surrounded by other objects. There is a small floor-level hole in the wall of the silo, into which Budge has placed several ceramic objects and lighted with a warm, incandescent light—in contrast to the dark, bluish light for the rest of the silo. It makes me think of a campfire. Above the central object are star-shaped ceramic figures.

I took them as representing actual stars. In the center of the ceiling of the silo is a large ceramic eye, seemingly gazing down on the scene below. If the theme of the exhibit as a whole is based around our primal need to create as represented by the paintings on the cave wall at Altamira, then what Budge has created perhaps is a depiction of hunter-gatherer types sitting around a campfire with a totem under the stars.

The largest piece was by Kathryn Kelley. Kelley is an artist I’ve written about frequently in thepast. Her work always combined a fierce physicality and emotionality and an intellectual underpinning. This probably helps explain why she moved away from the Houston area to get a PhD in studio art. Since she moved, I haven’t seen any new work from her locally, which made me sad. But she’s back for Sculpture Month. This three-part installation is called Disproportionate Dream Fragments, and visually doesn’t seem all that distinct from her earlier work. Instead of using cut-up inner tubes as material, she has found new, grungy recycled material to work with. I always worry that I might catch tetanus from just looking at Kelley’s sculpture.

The rusty bedsprings, the loose nails, all adds up to a somewhat dangerous installation. I know that there are artists who have approached this level of pure grunge, especially assemblagists like Robert Raushenberg, Wallace Berman, Ed Kienholz, and George Herms (some of my favorite artists). And yet, none of those artists has ever given me a feeling of physical menace like Kelley does.

That chair could kill you.

What these photographs utterly fail to convey is the clautrophobic sensation of being in these silos with the work. Kelley didn’t make it easy to breeeze through—you kind of have to squeeze past stuff to see everything. And I hardly need to say that photographing all the work in a given silo is next to impossible.

The installation seems to represent a homey, domestic interior made from scratch by a troglodytic family who only knew about things like beds, chairs, and wardrobes from television images. Their cargo cultic approximations of “home” are dangerous to use and not terribly functional.

Having said this, I suspect that Kelley has a well-thought-out reason for everything, amply backed by theory and with a highly personal underpinning. This has frequently been the case with her earlier artwork. Kelley keeps a blog, but for the past few years, most of her posts have been about why an artist should write. It feels like a very solopsistic project, an artist writing about artists writing. Lots of quotations and excerpts. Her writing is dense and poetic. I was hoping there might be some clues about Disproportionate Dream Fragments there, but I didn’t see any—nothing obvious, anyway.

The other Sculpture Month show I wanted to touch on was also a group show held at the house of sculptor Michael Sean Kirby. I like house galleries and apartment galleries. I couldn’t imagine doing it myself—my tiny apartment is too cluttered. But Kirby’s house is kind of perfect for this, presumbly because he, unlike me, is capable of keeping it tidy. The show in his house was called “After Altamira” and featured six artists. I’m going to mention two, partly because of all the photos I took that night, they had the only ones that came out good. I do want ot give a shout-out to Ronald L. Jones’ unphotographable installation, Cavity. His work, mostly made of webs of yarn stretched over a space, is extremely difficult to photograph.

Kamila Szczesna is a Galveston artist who often works with spherical shapes wrapped in stretchy materials. But for this exhibit, the spheres came out of their wrappings. The piece above, interwoven, is made of mouth blown glass and hair. The glass spheres look so delicate, like soap bubbles.

Patrick Renner is an artist I’ve followed for years, writing about his work on my blog and for other publications. His work is closer to the assemblagists I mentioned above than Kathryn Kelly art is—one can certainly see a little George Herms in introvert above. With Renner’s assemblage work, the component parts often have a personal meaning. In this case, they include “the only remaining side of a trick music box my paternal grandfather made when I was a kid” and a “bat house that used to be on my parents’ house.”

The spookiest detail was this tiny bat skeleton encased in acrylic.

Interview with Wes Hicks about Commerce Street Artists Warehouse, part 1

In 1985, some grad students in the U.H. art program were about to be kicked out. Their crime? They had completed their degree requirements and were graduating. They had studios at Lawndale, an off-campus site where the UH art department moved to after its on-campus building was damaged in a fire. It had been acting as the U.H.’s art department’s home since 1979. It was an enormous former factory and provided studio space for many of Houston’s best young artists as well performance space. (The story of Lawndale’s rise and triumph is told in Collision by Pete Gershon.) A couple of these art students, Kevin Cunningham and Wes Hicks decided to take their impending eviction and to try to recreate the Lawndale experience. They found a new ex-factory and established an art center containing studios and a large performance space. For legal reasons, it ended up with the name Commerce Street Artists Warehouse, or CSAW for short. In 2016, I interviewed several of the early residents of CSAW. I have finally gotten around to transcribing some of them and editing them.

Hicks is a painter. He grew up in Indonesia, studied art at the University of Houston, co-founded Commerce Street, and lived there until he was evicted in early 1994. While he was there, he ran the punk rock club, Catal Huyuk. This is kind of a long interview, so I am going to split it into several parts. Below is part 1 of my interview with Wes Hicks. In part 2, we’ll discuss some of the people who had studios or hung out at CSAW. The photos included come from various sources and I have tried to identify the source if I know it.If anyone knows where a given photo is from, please let me know!

ROBERT BOYD: You were a student at UH. Is that correct?

WES HICKS: Yeah, I was a student at the University of Houston, and which at the time was mainly Lawndale if you were a painting or sculpture student. We thought of ourselves as students of Lawndale University more than anything.

BOYD: My understanding is that you guys wanted to find someplace that had a similar feel to Lawndale, but that you ran yourself.

HICKS: Well, that was kind of it. Basically, what happened was we were all kind of getting booted out of Lawndale because we'd finished as many of the courses you could take there. They needed us to move along. Because we were seniors or graduate students who finished the program. Of course, we just wanted to stay on, but Gael Stack who was in charge said, "OK, this is your last semester here." I thought the idea was to organize a lot of the Lawndale friends that I had to start a communal art space in the warehouse district, emulating what all Lawndale was but with just us going it alone.

BOYD: How did you find the Commerce Street location?

HICKS: Kevin Cunningham did that. What happened was that all our friends kind of peeled off because basically they thought we were crazy. Except for me and Kevin Cunningham. Kevin knew Lee Benner through the skate scene, the Urban Animals. He took me to a party there in the building at Commerce Street, which at the time was just one big huge empty room with a lot of water on the floor, no lights or electricity, all the Urban Animals were skating around. That's how we kind of found it. We talked to Lee Benner; he knew the landlord because the landlord was Lee Benner's landlord. We just kind of went from there, one step at a time.

BOYD: When you found it, it was you, Kevin Cunningham, Deborah Moore. Rick Lowe was there at the very beginning, right?

HICKS: No, he wasn't. It was basically me, Deborah, Kevin and Jane--Jane Ludham--she was like a support team for Kevin. Then Jackie Harris and Steve Wellman and all those people were just kind of hanging around but no one would commit, so the whole thing looked like it was going to fall apart, then people just started showing up out of the woodwork, like Dr. Robert Campbell, then Rick Lowe. He was in very early on. We had to form a corporation because the landlord couldn't imagine signing a building without a corporate lease back in those days. We had to form a corporation, which as you know is really easy in Texas. Just 250 bucks and you drive to Austin. I think it was me, Robert Campbell, Kevin, Deborah, and Rick Lowe were the original corporate shareholders. We owned the thing, but none of that mattered. It was just for the landlord.

BOYD: So that's where those five names came from--they were on the paperwork, basically.

HICKS: Yeah, and we did have a structure where we would have votes and decide what we were gonna do. There were five of us, so if three voted one way and two voted the other. But we all agreed on everything pretty much. The big thing was about a third of the building in the back.

That was the big thing for me was the performance bay; it's almost a third of the building. It's a big huge empty room with really high ceilings and giant skylights, a massive entrance so that a huge crane could go in and out through giant steel doors. It's just this incredibly beautiful, almost perfectly square space. A little rectilinear with these giant pillars. I really wanted to keep that a communal performance bay that was open to anyone--not just us--that came to us with a good idea. We were going to do shows there regardless of quality or ideological baggage in the sense of "This is our art style--we don't like your art style." It's just going to be open to the public pretty much. I had to constantly fight for that. I think Deborah was pretty much on my side. This was always a bone of contention. Because she could have rented the space out and made all the rents much cheaper.

BOYD: Put up some walls and made some studios.

HICKS: Exactly. From the very beginning I was challenged. Jackie Harris wanted to use the space for her art cars. Make it into a giant art car development thing. From the very beginning, this was the big battle. I think that if I had lost and it had been developed into studios, then Commerce Street wouldn't have been Commerce Street.

BOYD: Kevin Cunningham made a really good point--you give a bunch of artists who are used to working in studios 27,000 square feet, suddenly doing a painting isn't enough. You have to fill that space somehow, and filling that space meant having a party or having an exhibition or having a performance of some kind.

HICKS: Yeah. In essence, that is what Lawndale was. Lawndale had a huge performance bay that was run by crazy, out-there people. First James Surls and then Chuck Dougan then Moira Kelly. And they always brought in really cutting-edge stuff that blew away the whole Houston art scene from Philip Glass doing operas early on; Moira Kelly having the Replacements come and really crazy bands that became famous later played Lawndale. The students were the stagehands, the volunteers who did all the work. That's where we go kind of like an apprenticeship. By the time we were starting Commerce Street, Kevin and I pretty felt like, hey, we can do this ourselves. Because we had learned from Moira Kelly and Dougan and James Surls and everyone how to it, and had worked with people who were masters of their craft on Philip Glass and stuff like that. And even if we didn't actually work with these people --have you ever heard of the band Sun Ra?

BOYD: Yeah.

HICKS: They played at Lawndale a lot, and I just kind of hung around with them and we just absorbed this stuff, as a really young person talking to the Sun Ra guys and telling us how it all goes down and what to do and the lives and touring. It was just a mind-blowing experience. When we had to leave Lawndale, we wanted that. Also, the economic situation in Houston at the time was almost impossible to imagine nowadays. The warehouse district was an abandoned wilderness. Literally a wilderness.

We were surrounded by abandoned warehouses. At that time, they hadn't all started to burn down. In the late 80s, people started to burn warehouses down for insurance money. Also, it was the deindustrializtion of the United States going on. The warehouse we were in was used by Westinghouse to build giant electric motors for ships. That had been gone for like 20-30 years by the time we got there.

[Commerce Street] was a totally black building. No lights. Rubbish in the front. All the toilets were rubbished. Homeless people had been crashing there. It was full of water because the ceilings were leaking. In the very back where Dr. Robert Campbell decided to build his space the roof was collapsed in an area of about 8 by 10 feet. And underneath that, plants were growing. So it was like a cave. In the daytime the sun would shine in. Actually, it was really beautiful. Pigeons and bats were living in there. It was just completely wild.

A photo from the late, lamented Public News in 1985. Photo by T. Ventura.BOYD: What did you have to do to make it habitable?

HICKS: Well, first we had to get permission from the landlord. And then we just started cleaning up. We made a deal with the landlord that she'd get an electric box for the front of the building. She'd bring the electricity to the building, and she would fix the roof. And once that was done, we'd start paying rent to the tune of I believe $1800 or $2000 a month. Which works out to about 14 cents per square foot, I think if I've got my numbers right. So that's what she did and that's how it started. We had this kind of very tenuous situation with the city, where the fire marshals were coming over and letting us do things that were plumbing and electrical ourselves, as long as we got electricians to come check it and make sure it was all done right. It was kind of an interesting relationship we had with the city.

Because of Houston's laissez faire no-zoning thing, they were willing to let us do really crazy stuff. They were shaking their heads--the fire marshal people. And they did weird things, too. Like one time, we were gonna do a huge benefit for the South Texas Nuclear protest project, because they were gonna build a nuclear plant in South Texas on Padre Island or some place. All these bands were going to play there and do a fundraiser for the protesters. The fire marshal came around and wrote me something like 13 citations for violations, and I knew this guy. He said, you know, if you're open tonight, I'm going to come here and arrest you; then he goes, if you're not open tonight, I'm just going to tear up these citations and we can just forget this ever happened.

BOYD: So what did y'all do?

HICKS: Oh, we weren't open that night. We told the 13 bands or however many there were that the show was shut down, which sucked ass. I can't go to jail and shut down this space. That was the end of that. But they actually moved it to another warehouse space. Some artist who apparently weren't aware of the situation. The fire marshal came there and arrested them and shut down their space. We were always at the mercy of the cops and the fire marshals who made it very clear to me that we existed only because they wanted this.

I don't think the cops really cared too much or the fire marshals cared too much about whether those buildings burned down or not. That was one of the things about Commerce Street, in relationship to the fire marshals and the Axiom, too. Because the way they were set up, you couldn't actually have a fire like those nightclub fires where 200 people died in Brazil and stuff. That couldn't happen in these places because there were all these giant exit doors that were open. Because it was so hot in Houston. People could just stampede out in a fire scenario.

BOYD: Once you started building it out as a studio space, at first it was just one big open space, right? How quickly did you guys build up walls and stuff.

HICKS: Well, actually it was two big open spaces. The back part of the building (the performance bay) was the original Westinghouse warehouse that was built in the 1920s or maybe even earlier. It was all wood with giant cypress posts that were like 18 inches by 18 inches, holding up a giant wooden ceiling. And that's now been demolished and taken away. It's a car park. And then the front of the building was added for war effort for World War II to build electric motors for the Victory Ships.

BOYD: The ones that were turned out pretty quickly for Great Britain.