Kevin Cunningham is a playwright, director, and producer involved in New York theater through the organization he founded and runs, 3-Legged Dog Media and Theater. But in the 80s, he was an art student then a writing student at the University of Houston. He was at Lawndale when it housed the art department, and he and Wes Hicks decided they wanted to maintain that Lawndale vibe in a new location. That location was the Commerce Street Artist Warehouse (aka CSAW), which existed from 1985 and 2007. I’m interested in CSAW and the effect it had on the Houston art scene, so I’ve been trying to speak to many of its early denizens. The first two parts of this project (it may be too grandiose to refer to these disparate efforts as a “project”) are my interview with Wes Hicks. (You can read part 1 and part 2 here.) This interview was conducted in 2016 and transcribed earlier this year.

[Note on the photographs: unless indicated, I do not have permission to use any of the photos here, unless I’m the photographer. Please let me know if you own the copyrights to any of them and I will happily remove them.]

“For a young artist, taking over 27,000 square feet changes your notion of the possibilities for scale.” — Kevin Cunningham

ROBERT BOYD: You were one of the first 4 people at CSAW. How did you four get together and how did it start?

KEVIN CUNNINGHAM: It was actually me, Steve Wellman, and Deborah Moore and Wes Hicks. We all had studio space at the Lawndale Art Center. We were all graduate students or students there. And we were looking for large space where we could do big things. I can’t remember if it was me or Wes, but one of us ran across this old empty warehouse, 27,000 square feet. And it had about six inches of styrofoam dust coated all over everything. And we talked to the landlord, and there's no zoning or anything, so we got it for $1000/month. And we split that between ourselves. We each took a part of the space. Wes and Deborah decided they wanted to live there, so they took the front area. And we each took a chunk of the floor. We got these high-pressure cleaners and spent weeks spraying the place out. It was a mess, a massive mess. And a nightmare. We'd get fiberglass in our skin. It probably was not very wise in terms of toxicity. But we were taking care of our own toxicity at the time.

BOYD: Before that, you were a grad student at UH art? Getting an MFA?

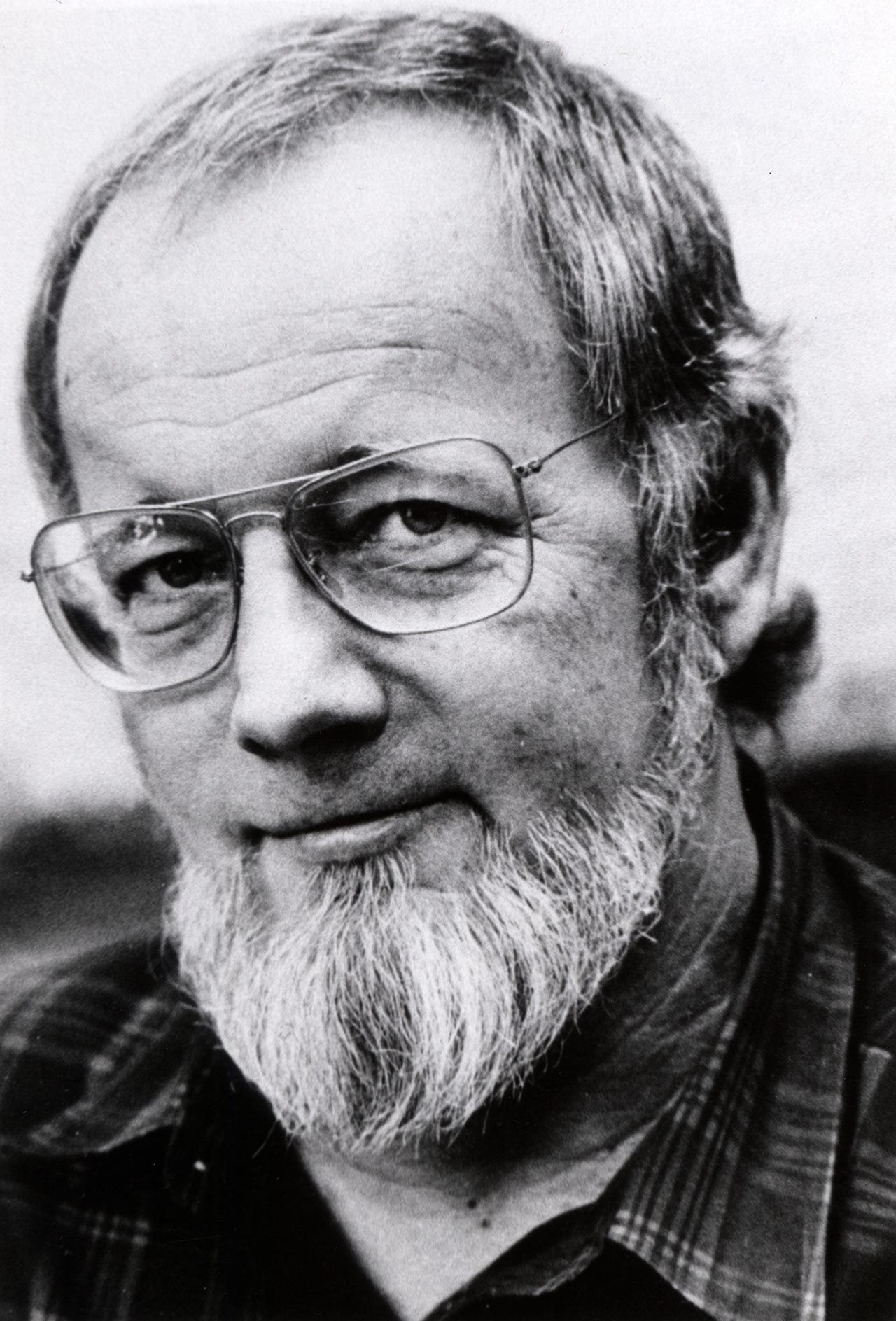

CUNNINGHAM: I was getting a BFA in sculpture and installation art, and I got really bored with my sculpture, which is how I ended up where I am now. I was tired of objects just sitting there. So I was actually taking a sophomore creative writing class, and I realized I had to turn in a short story the next day, so I just started writing a list of all the junk that had accumulated in my studio, as if I were an archeologist from the 40th century. I turned it in in desperation to my instructor. The next day, Donald Barthelme came storming into my studio with the story in his hand. "Did you write this?" I was like, "Uh... Yeah..." He was my favorite author at the time. I don't know if you've ever seen a picture of him. He sort of looked like God. And I said, "Yes." And he said, "Come with me." He took me and walked across campus into his graduate creative writing workshop. So I ended up getting a masters degree in creative writing and literature there at the UH Creative Writing Department.

It was a little bit before we formed CSAW that I ended up in the creative writing program. I was going through the creative writing program while I was working at CSAW.

BOYD: So while you were at CSAW, were you creating visual art?

CUNNINGHAM: Yeah. I was mostly making these big, crazy artists books.

BOYD: I read about them.

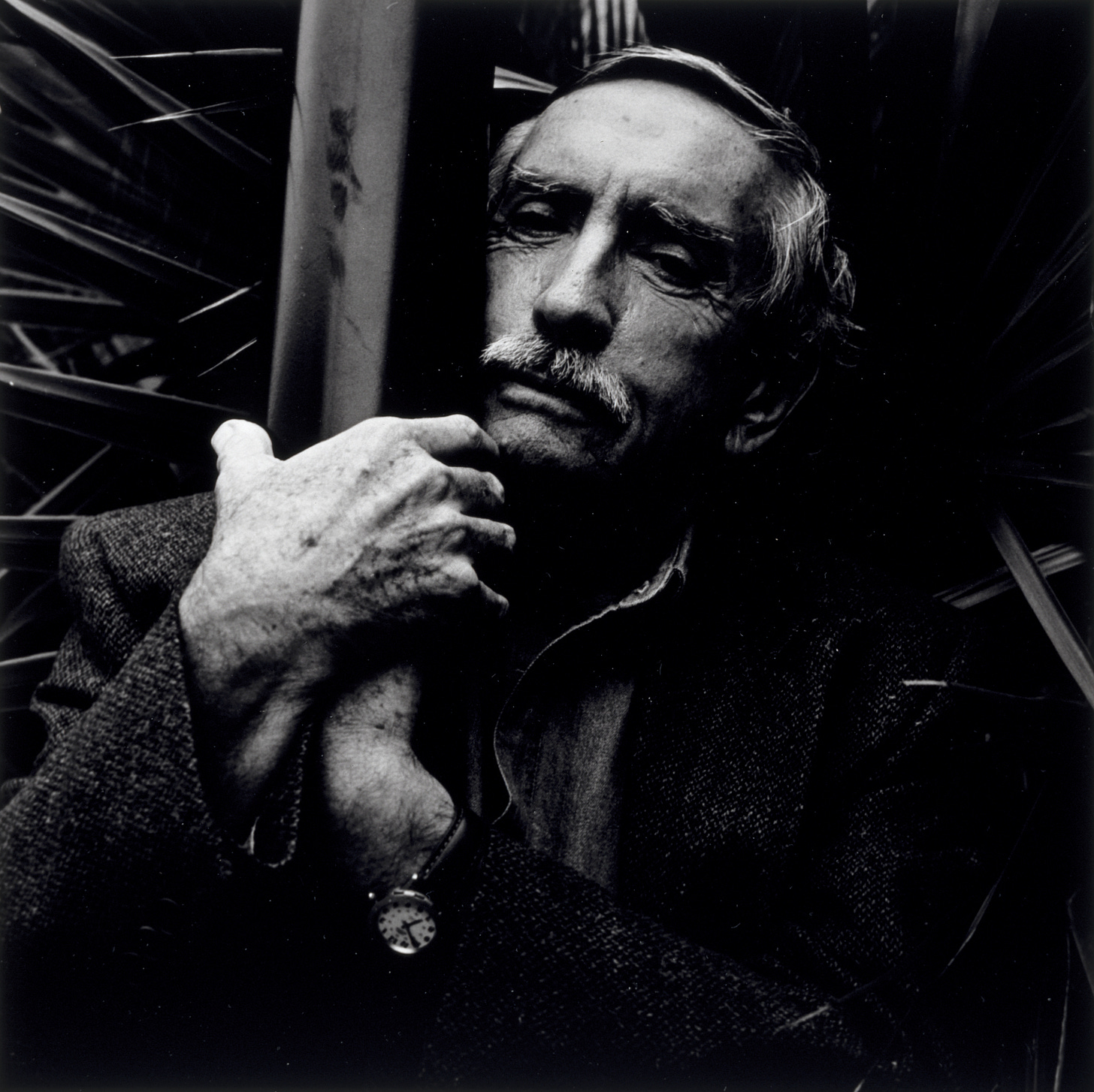

CUNNINGHAM: I was also working to try to incorporate video and sound into my sculpture at that time, too. And I also had begun doing these built performance events... Another thing that happened was that Don was insistent that I take poetry classes. And the poetry instructor at the time was this woman who began her poetry classes by saying, "You know, I've had writer's block for the last eight years." I still don't believe in writer's block. Randy Watson and I got in trouble because we flooded the workshop with 12 poems each a day. I tried to get out of it by sending a piece of fiction to Edward Albee, who was just then starting to teach at UH. To my shock and surprise, he called me up and said, "Is this Kevin Cunningham?" And I said, "Yes.""I would like you to join my playwriting workshop." I was one of his first playwriting students at UH. He became my friend and mentor for many years after that. So, I was also starting to move into theater at the time I was a student there at Commerce Street. I was doing lots of these collaborations, these performance installations with Michael Galbreth.

[Photo of Edward Albee by Suzanne Paul, Edward Albee, 1999, gelatin silver print, printed 2001, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, gift of Clinton T. Willour in memory of Kaye Marvins. © Estate of Suzanne Paul.]

[Photo of Edward Albee by Suzanne Paul, Edward Albee, 1999, gelatin silver print, printed 2001, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, gift of Clinton T. Willour in memory of Kaye Marvins. © Estate of Suzanne Paul.]BOYD: So, it does seem like the performance scene, such as it was, in Houston was very theater-oriented.

CUNNINGHAM: Like everything in Houston, at that time, one of the great things was that there weren't really any rules. And there were a lot of people who were getting together and trying different things. And Commerce Street in its best incarnations embodied that. There were a lot of painters at CSAW, but almost all of the artists who were working there got into performance or performative stuff. Michael Galbreth, did these endurance pieces there (where he'd lay face down in a big pile of sand for 24 hours). Wes was playing around with performance, and Deborah has always been a performer. She had her crazy, accordion-playing trickster character which she would embody. And Jim Pirtle also was involved. He wasn't a person with a studio, but he was there. Wes and I tried to keep that back bay open as a performance area. Where people could do performances. It was unequipped. The way we did things back then has now become one of my preoccupations which was that there was a lot of performance art that happens with clip lights. The reality was that performances are greatly enhanced by technology. We didn't do much technology. So yeah, we took that space over, cut out our little areas based on what we could afford, which wasn't much. I was working part-time at the Contemporary Arts Museum for six bucks an hour and I ran the Diverse Works bookstore at the same pay rate.

Michael Galbreth in 2013 at Notsuoh. Photo by Robert Boyd

BOYD: I remember that store. I bought zines there.

CUNNINGHAM: We were [at CSAW] and a couple of different guys rolled up in interesting cars. Nestor Topchy rolled up one day, in an old station wagon with some spherical forms in the back of it. Wes talked to him first. He invited him on in and gave him some space just to do some big objects; he wasn't going to stay or anything. And he ended up staying. And then Rick Lowe rolled up in a convertible one day. I think he was coming in from Alabama or Mississippi. I can't remember which. He introduced himself and just fell right in. I think Robert Campbell was the next person who came in, then Virgil Grotfeldt.

BOYD: Grotfeldt was older, right?

CUNNINGHAM: Yeah, Virgil was older. He was really on a roll in his painting. He needed a place where he could focus, and do things looking forward. It was real ad hoc. It just formed partly out of an existing network and partly out of people just wandering in. Nestor and Rick, you know.

BOYD: I talked to Nestor and he said he'd gone over to Lawndale because he'd been accepted into the MFA program, and someone told him about Commerce Street. So he just drove over.

CUNNINGHAM: Yeah. From my perspective, he just rolled up. I think Wes, Steve and I were out of school by then.

BOYD: What about the performances at CSAW? Aside from the one you told me about with Michael Galbreth. The one's you were involved with--were they theatrical in nature?

CUNNINGHAM: I would classify them as experimental theater. Lyn Miller directed some of them. He's still in Houston somewhere. Malcom McDonald was involved in a few crazy things, and Wes staged some things back there, a few really dangerous things. We did a piece called Sisyphus Distracted, which was a piece about a 7/11 worker. That was done by Joel Orr. He wrote the script and I directed it. There were all kinds of little performance art or dance kind of things that would happen there, almost spontaneously. One of the things that would happen is that these big parties would happen. People would do things spontaneously. There was a lot of that sort of thing going on. But generally speaking, it was mostly quiet around there, except for, you know, like Wes's temper tantrums.

BOYD: I've heard a little bit about that. Nestor said that's why he moved out.

CUNNINGHAM: Yeah. Most people did. Left because Wes was so difficult.

BOYD: I have the letter from the rest of CSAW evicting Wes. It lists a series of grievances. They all seem to be very recent grievances from those people, but it seems like they must have come right from the start.

CUNNINGHAM: Yeah. Pretty much.

BOYD: What about exhibits that were shown at CSAW while you were there? Were there many or any of visual art?

CUNNINGHAM: Yeah, there were several. Almost always it was a mix, you know. Once the walls were up, which took some time, we would put together exhibits. Different people would curate. I think Robert Campbell curated a couple of them. Wes was really active with Deborah in curating stuff. I did a couple of exhibits myself, and they almost always included a performance component in the back bay, and it included a party, of course. There was a pretty active scene there for about four years, probably.

BOYD: How long were you there?

CUNNINGHAM: I don't know. [laughter] I’m a recovering alcoholic and drug addict, now. I think I was probably there for two or three years. I was being advised by both Barthelme and Albee to leave Houston and move to New York. In 1990, two things happened. The Blue Man Group came on a P.S.122 field trip to Diverse Works. And I was actually able to help them get a big chunk of the show they were mounting at the time which turned out to be the Blue Man Group show that’s still running in New York. So they became convinced that I was a production stage manager, and offered me a job. And at the same time, Edward Albee gave me a residency at the Barn, his artist retreat in Montauk. I just moved to New York and started working with the Blue Man Group.

BOYD: This would be around 1990 or so.

CUNNINGHAM: 1990. Yeah, so I think this was probably when I left Commerce Street. I was probably still there at that time.

BOYD: What about writing? I know you wrote several things for the Public News.

CUNNINGHAM: I wrote for the Public News and for the Houston Press. Right before I left town, I made the mistake of pointing out a pattern of undue influence by Hiram Butler in the Texas collection at the Museum of Fine Arts, and was blackballed from writing in Houston.

BOYD:The Public News surely wouldn't give a shit about Hiram Butler.

CUNNINGHAM: No, it was the Houston Press.

BOYD: Really? Why do you think that would be the case?

CUNNINGHAM: That's just the way things were run back then. It was a tiny, tiny group of highly influential people out of River Oaks that were running everything. They didn't like to be embarrassed.

BOYD: Was this something you said in an article or what?

CUNNINGHAM: I outlined a pattern of what appeared to me to be undue influence by Hiram Butler and Alison De Lima Greene on the curatorial selections at the Museum of Fine Arts Texas art collection. Almost every Texas artist who was in that collection at the time was represented by Hiram Butler.

The article had no effect but to get me blackballed from writing about art in Houston. I started writing at the Houston Press with an article about the NEA when Mel Chin was singled out by them. I had done a few reviews. Mostly I focused on institutional criticism and commentary of institutions. Criticism of institutions in Houston. As Houston artists, a lot of us were getting national and sometimes international recognition for our work, but in town we were always as sort of class-Z cheap labor force, and so we couldn’t get any cred in Houston for a long time. I think the Art Guys were the first to get anything in the Contemporary Arts Museum. Surls and Chuck Duggan and those guys--Earl Staley and Derek Boshier--came to Houston with existing reputations. They didn't have the same problem that local home-grown boys did. There was also some competition from the Core program between Lawndale and the Core program--we all got together socially a lot, but the folks in the Core program seemed to have more of a leg up than the locals. There was a lot of controversy about that always; a lot of grumbling.

It was published. That's why I got blackballed. The response to that article was unnecessarily defensive. I'm just a schlub everyday-Joe artist writing my pain and pointing out a pattern. It was a pattern that was embarrassing to some people.

I wrote one about how Bob Bullock bought paintings and shot them for target practice.

BOYD: Bought paintings from whom?

CUNNINGHAM: Houston artists. I can't remember who the artists were exactly. But he apparently bought this painting and used it for target practice.

BOYD: It wasn't finished until he shot it.

CUNNINGHAM: I'll admit that it was a good idea, I thought.

BOYD: Criticism by the gun. What a weird thing to do. If you don't like a painting, why buy it in the first place?

CUNNINGHAM: In talking to him, it wasn't that he disliked the painting. He just got a wild hair up his ass.

___________________________________________________________________________

CUNNINGHAM: I'm not sure how CSAW is thought of in Houston. The way it developed in the end is kind of emblematic of what happens to really critical art movements all over the planet really. A little less in Europe. But here in the United States, artists often come into a really blighted area and take over a space. Basically, what happens is their lawyers come in and see the space then take it over and turn it into high end lofts.

BOYD: That didn't happen with CSAW. It's still an artists’ space. But the rents are higher.

CUNNINGHAM: So it's rich artists.

BOYD: It's Sunday painters, really.

CUNNINGHAM: Yeah. Those aren't artists. People who started CSAW, most of them anyway, have spent their lives making art as professionals, usually at pretty great personal cost. None of us are wealthy. Some of us are kind of well-known or famous. Have created work, that, you know--my work has been in the Venice Biennale and Sundance. Sort of the lawlessness of Houston was one of the ways that place could happen. Also, it was kind of inevitable given the way that Houston runs. It was a company town that sort of controlled by a pretty small cadre of wealthy people at that time. I don't know what it's like now. That CSAW would ultimately be taken over by people with money. It will succeed to death, which is how a lot of these things happen. Here in New York, it's become the business model for real estate people.

BOYD: Yeah. For sure.

CUNNINGHAM: That's sort of sad because, in its early days, anyway, it was really a nexus for creativity in Houston. And a lot of people came through that building that contributed significantly to Houston's art world and its credibility there. Walter Hopps was hanging around. It was a very fecund place, an environment where creativity was really the only thing that was going on, almost. It's hard to find those places. Now I have a place here in New York, 3LD that's grown out of my experience at Commerce Street Artists Warehouse, a 12,500 square foot art/technology center down below ground zero that's built out of the ground floor of a parking garage. My rent here is $24,000 a month and my electric bill is $16,000 a month. A lot of creativity happens here, but there's a huge preoccupation with survival and money. It interferes with that a lot. It didn't exist in the early days of Commerce Street. We could always come up with 1000 bucks for the landlord. There was no zoning or code requirements so we could actually outfit the place as we needed without undue expense or permitting or any of that crap. That was nice. And probably now non-existent.

BOYD: There are places a little bit like that now, where people manage to take over skuzzy old warehouses on the East Side. But you're right--it's harder to do, and I think it's more expensive. One thing about Commerce Street is that people left who went on to buy things. Jim Pirtle owns a building; Project Rowhouses is owned by itself. They don't have to worry about someone evicting them.

CUNNINGHAM: A lot of us did go on and maintain our bad habit of turning unused industrial spaces or blighted spaces into something good. Rick's probably the best example of that. I also have a pretty well-run art/technology center here in New York. Jim is Jim: he's going to do what he does in his own inimitable way. The thing is, here in New York, that pattern has driven the city to a point where we're reaching a point of cultural stagnation. Where we're more of a tourist center, and it's very, very difficult for a young artist to get started. In 1996, the New York Times asked Richard Foreman, the experimental director, the grandfather of experimental theater in New York, what was the biggest thing standing in the way of a young artist in New York, and he said, real estate. It's truer and truer every day now. Now we're overrun by large, multinational retail entities and banks competing with artists. We don't have a snowball's chance in hell. I'm here, and I just finished my second big eviction fight with my landlord, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, and sometimes I long for those days when you could just take over a warehouse, clean it up, and make art.

BOYD: Have you thought about moving further from Manhattan?

CUNNINGHAM: Yeah. If I didn't have a 30-year-lease, I would have been in Berlin 10 years ago. The environment for the arts in the United States is not just difficult, it's absolutely hostile. There are many. many forces arrayed against people who want to create new things. It's not just financial/real estate. There're also ideological issues. The culture wars have just gotten worse. I started my art career in 1980. Curated my first group show right when the culture wars were really starting, and we haven't seen it stop. The philanthropic support for the arts has cratered. After this recession, we lost the Rockefeller Foundation, American Express left cultural funding. Altria is gone a long time ago. All the big foundations that used to fund culture either don't fund culture at all, or they require the cultural activity to serve some other purpose that doesn't have anything to do with art-making: education, or social good. The idea of art as a primary human activity that's important to human culture--has almost disappeared in the United States. I go to Europe and tell people I'm an artist, they treat me like I was saying I was a doctor or lawyer or something. It's an honorable profession that requires perseverance and a long apprenticeship. And here, I'm still sort of a cross between your crazy uncle and the town drunk. I have to prove myself as a business person before they'll talk to me or help me with any resources. It's almost untenable in a lot of ways.

But we keep doing art. You can see behind me that there's a plaque from one of my plays that goes around somebody's neck that says Don Quixote. There's another plaque next to it that's going to be Sisyphus. It's different now. It's not the same as it was back then. It's much more difficult in all spheres. It is what it is. That opportunity in that moment was really special in Houston. I think it was a really great mix of things happening at the same time that produced a few really good artists. And what produced them was an environment of absolute intellectual and maybe even moral freedom. A feeling that you could do whatever you wanted to with impunity. And there was a huge community behind you. I don't know what it's like there now, but I get the sense that the support structure is much less vibrant, and that there isn't as much new blood flowing through the city as their used to be in terms of art.

BOYD: There's nothing quite like CSAW. One thing that I think CSAW sort of embodied was a change in direction for art in Houston. A lot more performance. It was a painters’ town before Commerce Street came along. Right when Commerce Street came along, it had just celebrated painterliness by having the Fresh Paint show.

CUNNINGHAM: We had Mel Chin running around. He was interesting. He did a lot of different things. At James Harithas’ house, there were still big parties there where Staley would be there and Surls and Burt Long and... The other thing is that Commerce Street Artists Warehouses wouldn't have existed without Lawndale. Surls took over that big warehouse on behalf of the University of Houston, that environment gave a big, open concrete space that you can get messy in. It became a necessary modus operandi for all of us, I think.

BOYD: I think that kind of thing encourages performance. It happened in New York back in the 60s when they started doing Happenings. These people had lots of loft space, and they do something in the loft space besides paint. Let's have a bunch of people do some kind of performance of some kind. The big space idea was helped the direction of Houston's art change somewhat from individual painters in their studios to people getting together and doing crazy things at Commerce Street or Catal Huyuk or Zocalo or where ever.

CUNNINGHAM: For a young artist, taking over 27,000 square feet changes your notion of the possibilities for scale. I wouldn't have done the films I've done, I wouldn't have done 30,000 square foot major media installations, probably. I never would have even thought about that if I hadn't had my experience at Commerce Street and Lawndale.