Robert Boyd

![]()

Out of Sight: The Los Angeles Art Scene of the Sixties![]() by William Hackman (2015, Other Press)

by William Hackman (2015, Other Press)

![]()

Creating the Future: Art and Los Angeles in the 1970s![]() by Michael Fallon (2014, Counterpoint)

by Michael Fallon (2014, Counterpoint)

![]()

Hairy Who & the Chicago Imagists![]() by Leslie Buchbinder (2015, Pentimenti Productions)

by Leslie Buchbinder (2015, Pentimenti Productions)

![]()

Pow Wow: Contemporary Artists Working in Houston, 1972-1985, lecture by Pete Gershon with a panel discussion including Lynn Randolph, Marilyn Oshman, Richard Stout, Earl Staley and Kelly Alison

I grew up in Houston and have been interested in art since I was a child, but before I was even aware that Houston had an art scene of its own, I was interested in the scenes in Chicago and L.A. This interest began in the early 80s in college. I was taking a class called "Art Since the 40s," taught by William Camfield. One day, he showed two slides in succession, one showing a painting by Jim Nutt and one a painting by Ed Paschke. This work, shown in passing among hundreds of other slides, grabbed me hard. I ended up writing a paper about the Hairy Who for that class. This artwork was not well known--the research materials I dug up at the library were paltry. But I was able to determine from them that Chicago had a different thing going on than New York, and that thing had been around since Ivan Albright was painting there back in the 30s and 40s. Chicago's art was figurative and grotesque, and it had apparently been written out of contemporary art history, which was often presented (and still is) as a linear path. Chicago wasn't on that path.

While in school, both Edward Keinholz and Robert Irwin came and visited the campus. These were two very different artists, but they had Los Angeles in common. Later I read Lawrence Weschler's biography of Irwin, Seeing Is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees![]() , and it connected the artists (and many others). That's where I first read about the Ferus Gallery.

, and it connected the artists (and many others). That's where I first read about the Ferus Gallery.

Perhaps the final step that cemented my interest in art scenes from the provinces was seeing the mind-blowing Helter Skelter exhibit at MOCA in Los Angeles. It made Los Angeles art feel sexy and dangerous, and suggested that the scene was vital.

I came to realize that Chicago and Los Angeles had their own distinct art histories. This is important because for the most part, I'd been taught that from the 1940 to 1980 or so, the history of art was essentially the same thing as the history of New York art. Now I saw how laughably wrong this was, because while what was happening in New York and Los Angeles overlapped in some aspects with New York and mainstream critical consensus, they were pretty distinct. And it started occurring to me that if Chicago and Los Angeles could have their own art histories, maybe other cities could. Maybe even Houston.

Los Angeles

Fortunately, the art history of Los Angeles is well documented in catalogs of museum exhibits and in other books. The Pacific Standard Time exhibits (organized in 2011 by the Getty Museum but involving the cooperation of 60 art institutions in Southern California) produce quite a few exhibition catalogs covering LA art from 1945 to 1980. Individual L.A. based artists have been well documented in exhibition catalogs and monographs (in my library, I have such books on Mike Kelley, Ed Kienholz, Lari Pittman, Ken Price, Raymond Pettibon, etc.) In addition to Pacific Standard Time, there have been other exhibits devoted to Los Angeles art, with their own attendant catalogs. Time & Place: Los Angeles, 1957-1968 was exhibited in 2008-09 at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, and Los Angeles 1955-1985: The birth of an art capital at the Centre Pompidou in 2006. Both of these shows produced excellent catalogs. The Pompidou's, called Catalog L.A.: Birth of an Art Capital 1955-1985, is an obsessively detailed timeline of the entire era.

Beyond catalogs and monographs, there have been biographies (such as the Robert Irwin book mentioned above) and histories, including the excellent Rebels in Paradise: The Los Angeles Art Scene and the 1960s![]() by Hunter Drohojowska-Philp and the oral history compiled by Kristine McKenna, The Ferus Gallery: A Place to Begin

by Hunter Drohojowska-Philp and the oral history compiled by Kristine McKenna, The Ferus Gallery: A Place to Begin![]() (as well as the documentary The Cool School: Story of the Ferus Art Gallery

(as well as the documentary The Cool School: Story of the Ferus Art Gallery![]() by Morgan Neville). With all this, it would seem that another book on the L.A. art scene in the 1960s would be irrelevant. But there are always new details to unearth, and points of view not yet discussed.

by Morgan Neville). With all this, it would seem that another book on the L.A. art scene in the 1960s would be irrelevant. But there are always new details to unearth, and points of view not yet discussed.

So even though I consider myself pretty much an expert on L.A. art in the 60s by now, I went ahead and ordered William Hackman's Out of Sight: The Los Angeles Art Scene of the Sixties. There isn't much here as far as the artists go that you won't find in Rebels in Paradise. But Hackman understood that institutions are important in a way that was only hinted at by Drohojowska-Philp. (That said, I consider Rebels in Paradise to be the superior book.) Obviously the rise and fall of one particular institution, the Ferus Gallery, is central to both books and any book dealing with L.A. in the 60s.

![]()

Artists outside the Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles, 1959. Clockwise from top: Billy Al Bengston, Irving Blum, Ed Moses, and John Altoon. Photo by William Claxton. - See more at: http://blogs.getty.edu/pacificstandardtime/explore-the-era/archives/i126/#sthash.eIk8NWu7.dpuf

To me it's an old story, but I realize my obsessions are not universal, so here's a nutshell history of the Ferus Gallery. In 1957, Walter Hopps and Edward Kienholz, two young men involved in the avant garde of the L.A. art scene, decided to partner up and open a gallery together on La Cienega Blvd., a commercial street in L.A. that already had several art galleries. They showed work by the cutting edge of L.A. and San Francisco art. But the gallery wasn't at all profitable, so in 1958, Irving Blum bought out Kienholz's share, moved the gallery across the street to a nicer space, trimmed the bloated roster and worked hard to turn Ferus into a gallery that made money for its artists and its owners. Blum gave Andy Warhol his first solo show and in general started showing more New York artist, as well as a very choice selection of L.A. artists. It has to be said that Kienholz, Hopps and Blum all had good eyes for art. Among their artists were people like Robert Irwin, Ed Moses, Ken Price, Ed Ruscha and Larry Bell. They really put Los Angeles art on the map at a time when art was utterly dominated by New York. In 1962, Walter Hopps left Ferus to take a job as a curator for the Pasadena Art Museum, and in 1967, Blum closed Ferus Gallery. It was just too hard to get collectors to part with their money for contemporary art in L.A. He moved to New York and started the Irving Blum Gallery. Of course, Hopps, Kienholz and Blum each achieved great success subsequent to the rise and fall of Ferus as an artist, as a curator/museum director, and as a gallerist respectively.

![]()

The Los Angeles County Museum on Fire, 1965–68, Ed Ruscha. Oil on canvas. 53 1/2 x 133 1/2 in.

But what Hackman also covers are some of the other institutions that formed the art ecology of L.A. in the 60s. The Los Angeles County Art Museum, for example, was founded in 1961 and moved into a large modernist structure on Wilshire Blvd. in 1965 (this new structure is the subject of Ed Ruscha's famous painting, The Los Angeles County Art Museum on Fire). The museum's board of directors were so self-serving that almost as soon as the museum was built, they fired museum director Richard Brown after he demanded that the museum be run more professionally (and not as a gallery for the board's art collections). This was followed by years of mediocrity.

Even more pathetic than LACMA was fate of the Pasadena Art Museum. After groundbreaking shows curated by Hopps, the museum board was convinced by Hopps that the museum should move into a custom built structure (it was housed in a leased mansion). Hopps had few allies on the museum board who, it was said by Hopps' predecessor Thomas Leavitt, cared more for "the quality of the parties" than the "quality of the exhibitions." (And that attitude persists in Houston as well, as a casual perusal of CultureMap confirms.) There was a split on the board between the older members (conservative Pasadena WASPS) and the newer members (liberal Westside Jews) about the type of art the museum should be dedicated to (the Westside contingent supporting a more modern approach, following in the success of Hopps' exhibits). Also, because the museum had long run on noblesse oblige, there was no institutional capacity to raise the money necessary to build a new building. Hopps was forced out and left L.A. for good. (He ended his career as director of the Menil.) By 1974, the Pasadena Museum was in such financial trouble that it was taken over by Norton Simon and became the Norton Simon Museum. Considering that it had been the vanguard museum for contemporary art for a few years, this was a terrible loss.

Art galleries also had their troubles. Ferus was just one of many galleries that closed in the late 60s in L.A. Their problem was similar to what Houston galleries face today--their potential customers would prefer to buy art in New York, which is only an airplane ride away. That was the situation at the end of the 70s--no commercial or public institutions could be counted on to support contemporary art in a reliable way in Los Angeles, despite the fact that that it was the third largest city in America.

This is where Creating the Future: Art and Los Angeles in the 1970s comes in. Like artists all over the U.S., by the 70s in Los Angeles, there were serious questions about the institutions. Aside from their failure to support L.A. art, it was dawning on artists that these places were sexist and racist as well. Michael Fallon shows how parallel art worlds developed through alternative subcultures in L.A. First is feminist, and the major catalyst here was Judy Chicago. After developing a feminist art program at Fresno State, she joined up with Miriam Schapiro at CalArts to continue this work. They founded "Womanhouse" in a mansion near downtown (far from CalArts's new Valencia campus).

That this came out of CalArts is not too surprising. It was established in 1961 when the Disney brothers merged the Chouinard Art Institute (where many of the "cool school" 60s generation of LA artists studied and taught) and the L.A. Conservatory of Music. They wanted a school that would churn out the kind of skilled artists, musicians and composers that the entertainment industry needed. CalArts is still a leader for teaching animation. But it really took off in unexpected directions in 1971, when it moved to its new campus in Valencia, a distant northern suburb of Los Angeles. The school hired people like Chicago, John Baldessari and Allen Kaprow to teach. Because of this, L.A. suddenly became a hotbed of both performance art and conceptual art. The artists they taught became some of the most important artists of the 70s and 80s--though few remained in Los Angeles. Baldessari in particular encouraged them to move to New York because he recognized it would be difficult for them to maintain careers in L.A.

![]()

Suzanne Lacy, Car Renovation, 1972

Much of the book deals with the spread of performance and conceptual art in L.A., focusing on artists like Chris Burden, Mike Kelley (whose career would blossom in the 80s, but the groundwork for which was laid in the 70s), Suzanne Lacy, Paul McCarthy, Bas Jan Ader and Allen Ruppersberg. This work seems somewhat divorced from the failed institutions of the 60s, but often connected with educational institutions for support. (I've always wondered if artists who wish to decommodify art through performance or ethereality don't see their art school salaries as another form of commodification. I do.)

![]()

Llyn Foulkes, Who's on Third?, 1971-73

But Fallon points out that painting continued in Los Angeles. So he pays attention to the heterogeneous painting of Llyn Foulkes, Vija Celmins, Robert Williams, etc., while correctly refusing to identify any school of painting in L.A. When Fallon identifies a trend or tendency, it tends to be self-defining (feminist art or Chicano art), or it is something he made up himself. For example, he names a group of artists "New Romantics"--artists who were attracted in one way or another to the dark side of Los Angeles. He places Paul McCarthy, Kelley, Terry Allen, Bettye Saar and Tony Oursler in this group (and Foulkes on its edge). This seems a little dubious, but many of these artists ended up in Helter Skelter: L.A. Art of the 1990s at MOCA, which had a similarly dark theme, so maybe he's right.

Fallon also looks at art that almost had no relationship to the art world. The mural movement in L.A. in the 70s was largely Chicano and largely existed outside the heavily theorized world of conceptual and performance art. It was unabashedly populist, for one thing, and highly political. But all art worlds overlap to one degree or another--Asco, the conceptualist Chicano collective was one such overlapping point. Likewise, Fallon includes a chapter on "Lowbrow" art, the art that evolved out of custom car, surf and skateboard culture. In the 70s, this work existed defiantly outside the mainstream artworld, but time heals all breaches--Mike Kelley and Jim Shaw persuaded curator Paul Schimmel to include Robert Williams, the leader of this school of art, in the Helter Skelter exhibit in 1992.

If it sounds like a lot of the artists in this book achieved notoriety after the 70s, that's true. The impression one gets reading Creating the Future is that artists spent the decade laying a groundwork for future success. This is true not only for Mike Kelley and Robert Williams, but for James Turrell, Vija Celmins and even John Baldessari.

Creating the Future is necessarily unfocused. The simple truth is that the number of artists and the variety of artists was going to necessarily be bigger than in the 1960s. That the art scene could be defined by one institution, the Ferus Gallery, in the 1960s was a highly unusual situation. I like that Fallon doesn't try to create any false connections between scenes and artists where none really exist. Los Angeles is a city big enough to contain multitudes, artistic tendencies that are in opposition to or orthogonal to other trends. I see this in Houston today, with cliques and styles that don't really exist for each other.

Chicago

Chicago differs greatly from Los Angeles in one important way. Its artists have never become central or important to contemporary art history in the way that some of Los Angeles' artists finally did. When I think of really well-known Chicago artists, I can only think of a few (for example, Leon Golub, Nancy Spero, Ed Paschke, Kerry James Marshal and Theaster Gates. And Golub and Spero were only rediscovered in the 80s, after long careers painting in Chicago). I think most people conversant with contemporary art might have heard of the Hairy Who without necessarily being able to name the artists involved. If they saw a Roger Brown painting or an H.C. Westermann sculpture, it might seem familiar. Here's a completely unscientific way of stating this imbalance. In my personal book collection, I have 21 books dealing with Los Angeles art and only seven dealing with Chicago art. And none of the seven are a general history like Out of Sight and Creating the Future. I would love to read such a book, if it existed.

That said, a new documentary, Hairy Who and the Chicago Imagists directed by Leslie Buchbinder, does try to fill in a few blanks. Right up front, it admits Chicago's marginality. "The story of 20th century American art is already written. It is not a story about Chicago." The subject of this film are a group of artists who started exhibiting in the 1960s. Most are completely unknown today, but a few--Jim Nutt, Karl Wirsum, Ed Paschke and Roger Brown have had major solo exhibits. They were all figurative painters. They weren't pop artists exactly, but they were influenced by popular culture, especially things on the fringe of popular culture. Instead of being influenced by shiny new products at the supermarket or mass-market ads, they were more likely to be influenced by the kinds of oddball items they found at flea markets or botanicas, early animated cartoons, pinball machines, carnival sideshows and painted commercial signs. But they were also influenced by outsider art and earlier Chicago artists like H.C. Westermann. Their work was often sexual and impolite--in this way, it seems similar to the contemporaneous art being produced by the underground cartoonists. One subgroup of the Chicago Imagists, the Hairy Who, even produced their own comic books to act as catalogs for their exhibits.

The structure of the film is to focus on one artist at a time, having that artist speak about his or her own work, and having other Imagists artists speak about their work, and then artists who were influenced by them. For instance, Kerry James Marshall and Chris Ware both conment on Jim Nutt's work, and Jeff Koons about Ed Paschke.

If Ferus is central to Out of Sight and CalArts to Creating the Future, the Hyde Park Art Center and the Phyllis Kind Gallery are the important institutions in Hairy Who and the Chicago Imagists. Don Baum was the director of the Hyde Park Art Center, and his stated goal was to give new artists a venue to show their work. Much of this was done through large group shows, but some artists wanted a smaller group show so that each of them could show multiple works. So Nutt, Suellen Rocca, Art Green, Gladys Nilsson and Jim Falconer proposed this to Baum. Baum suggested they include Karl Wirsum, which turned out to be an inspired addition. They brainstormed the name, Hairy Who, and it caught the attention of the public. (The name for the group makes them sound like a rock band, but they weren't a collective in the sense of making collective artworks--each artist did their own thing.)

They were so successful that they had two more shows together at the Hyde Park Art Center, and Baum realized that he had stumbled onto a good thing. Instead of having shows with dozens of artists, have shows with five or six artists and give them a slightly wacky name. The Nonplussed Some consisted of Ed Paschke, Ed Flood, Sarah Canright, Richard Wetzel, Robert Guinan and Don Baum, and it was followed by the False Image, consisting of Roger Brown, Christina Ramberg, Philip Hanson and Eleanor Dube.

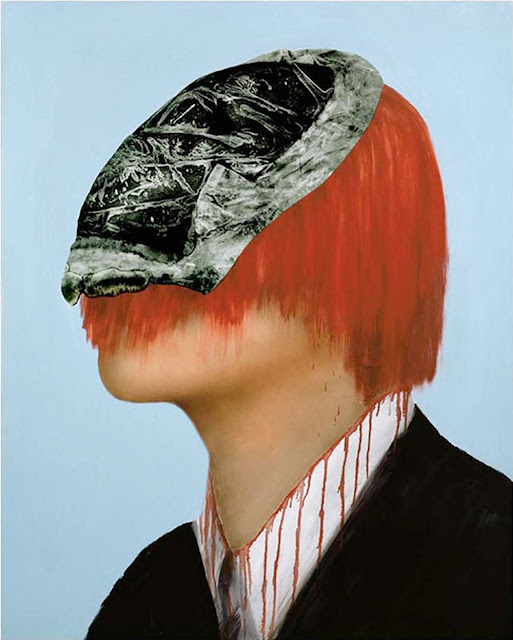

![]()

Christina Ramberg, Head, 1969-70

Just as Baldessari was a key teacher for many of the 70s era LA artists (and artists who left LA), Ray Yoshida served the same role for 60s era imagists. One of his main messages was to collect things and fill your life with your collections. He wasn't talking about expensive art collections (although perhaps not excluding them), but accumulating objects that obsess you and that collectively come to define you. Ed Paschke had photos of circus freaks; Roger Brown and Karl Wirsum had collections of oddball objects; many of the Imagists collected things from the flea markets of Maxwell Street. Part of the Hairy Who's second exhibit was a glass case full of things they collected. This was for Yoshida the starting point for a person's art. All the Imagists are visual bricoleurs, finding subject matter in the strange stuff they found on the street. For instance, there is a section Christina Ramberg's diary where she talks of finding an old romance comic on Maxwell Street, seeing all these drawings of the protagonist from the rear and being inspired to paint a series based on them.

![]()

Ed Paschke, La Chanteuse, 1981

Phyllis Kind Gallery was founded in Chicago in 1967, and she became the primary gallery for many of these artists over the next decade. Jim Nutt remarks in the film that it was probably a mistake for so many of them to put all their eggs in that one basket, but Kind was aggressive in marketing their work. Over the course of the 70s, she was successful in placing the work with collectors and encouraging museums all over the world to show and collect the work. For instance, Walter Hopps curated a show of Chicago Imagists that originated in São Paulo and which traveled throughout Latin America. But like Irving Blum, she saw the writing on the wall and moved her operation to New York, shifting focus to outsider art. She says, "You do what you have to do when you have to do it."

As quickly as they found success, they became the reactionary establishment in the eyes of the younger Chicago artists who were influenced by conceptualism and theory. You could read the hostility towards them in the pages of the New Art Examiner, which started publishing in Chicago in 1973 and for years was another important institution on the local scene. In 1974, Frank Pannier wrote, "Here [in Chicago], through the continual re-hash of the same old tired 'Dada Surrealist' concepts and also through the constant proliferation of simple-minded provincial aesthetics, most 'pictorial' art is reduced to that infectious manifestation of visual gonorrhea most clearly typified by the 'Hairy Who?' and its many offspring." ("A Painter Reviews Chicago, Part 1," Frank Pannier, The New Art Examiner, Summer 1974)

It seemed that the Imagists had gone out of style. The art market rejected them, the critics forgot them, younger artists abjured them. But what comes around goes around and they seem to have come back, with recent exhibits at the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art (2011) and solo Jim Nutt exhibit at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago (2011). Karl Wirsum and Gladys Nilsson have relatively new gallery representation in New York City, and Philip Hanson's paintings were in the most recent Whitney Biennial (they were my favorite works in the show). The film concludes with a variety of contemporary artists talking about how important the work is to them, so their influence is strong even if these artists are still not well known outside Chicago.

Houston

In these two books and this documentary, one can see similarities to L.A. and Chicago in Houston's art scene. Houston is a younger city, of course. While there were interesting artists in Houston in the 1960s, it wasn't until the 70s that the local art scene took off. So where is a book or documentary film about that era in our city's art history? It's coming. A couple of weeks ago, Pete Gershon, author of Painting the Town Orange, gave a presentation on his work in progress, Pow Wow: Contemporary Artists Working in Houston, 1972-1985. He's been interviewing artists and people involved in Houston's art world for over a year now, since Bert Long's death in early 2013. Gershon had on a volunteer basis been cataloging Long's papers when Long suddenly died. Gershon said that even though he had spent a considerable amount of time with Long, there were still questions he wanted to ask. From there he realized that there are a number of Houston artists in their 60s, 70s and 80s about whom he could say the same thing. One thing lead to another, and this book was born. Rather than review something that doesn't yet exist except as a partially completed manuscript, I want to present a talk that Gershon gave about the work in progress at the Glassell school (filmed and edited by J.J. Avkah).

I believe regional art histories are extremely important. We feel sometimes that the modern world homogenizes culture, but the examples of L.A. and Chicago demonstrate how wrong that is--two cities in the U.S. produced utterly distinct art at exactly the same time. I should say three cities (including Houston). And each was distinct from New York. But this documentary and the two books also show how difficult it is to maintain and nurture a regional art scene. It can all go away and be forgotten, unless writers, archivists, film-makers and other keepers of memory do their work.

Out of Sight: The Los Angeles Art Scene of the Sixties

by William Hackman (2015, Other Press)

by William Hackman (2015, Other Press)

Creating the Future: Art and Los Angeles in the 1970s

by Michael Fallon (2014, Counterpoint)

by Michael Fallon (2014, Counterpoint)

Hairy Who & the Chicago Imagists

by Leslie Buchbinder (2015, Pentimenti Productions)

by Leslie Buchbinder (2015, Pentimenti Productions)

Pow Wow: Contemporary Artists Working in Houston, 1972-1985, lecture by Pete Gershon with a panel discussion including Lynn Randolph, Marilyn Oshman, Richard Stout, Earl Staley and Kelly Alison

I grew up in Houston and have been interested in art since I was a child, but before I was even aware that Houston had an art scene of its own, I was interested in the scenes in Chicago and L.A. This interest began in the early 80s in college. I was taking a class called "Art Since the 40s," taught by William Camfield. One day, he showed two slides in succession, one showing a painting by Jim Nutt and one a painting by Ed Paschke. This work, shown in passing among hundreds of other slides, grabbed me hard. I ended up writing a paper about the Hairy Who for that class. This artwork was not well known--the research materials I dug up at the library were paltry. But I was able to determine from them that Chicago had a different thing going on than New York, and that thing had been around since Ivan Albright was painting there back in the 30s and 40s. Chicago's art was figurative and grotesque, and it had apparently been written out of contemporary art history, which was often presented (and still is) as a linear path. Chicago wasn't on that path.

While in school, both Edward Keinholz and Robert Irwin came and visited the campus. These were two very different artists, but they had Los Angeles in common. Later I read Lawrence Weschler's biography of Irwin, Seeing Is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees

, and it connected the artists (and many others). That's where I first read about the Ferus Gallery.

, and it connected the artists (and many others). That's where I first read about the Ferus Gallery.Perhaps the final step that cemented my interest in art scenes from the provinces was seeing the mind-blowing Helter Skelter exhibit at MOCA in Los Angeles. It made Los Angeles art feel sexy and dangerous, and suggested that the scene was vital.

I came to realize that Chicago and Los Angeles had their own distinct art histories. This is important because for the most part, I'd been taught that from the 1940 to 1980 or so, the history of art was essentially the same thing as the history of New York art. Now I saw how laughably wrong this was, because while what was happening in New York and Los Angeles overlapped in some aspects with New York and mainstream critical consensus, they were pretty distinct. And it started occurring to me that if Chicago and Los Angeles could have their own art histories, maybe other cities could. Maybe even Houston.

Los Angeles

Fortunately, the art history of Los Angeles is well documented in catalogs of museum exhibits and in other books. The Pacific Standard Time exhibits (organized in 2011 by the Getty Museum but involving the cooperation of 60 art institutions in Southern California) produce quite a few exhibition catalogs covering LA art from 1945 to 1980. Individual L.A. based artists have been well documented in exhibition catalogs and monographs (in my library, I have such books on Mike Kelley, Ed Kienholz, Lari Pittman, Ken Price, Raymond Pettibon, etc.) In addition to Pacific Standard Time, there have been other exhibits devoted to Los Angeles art, with their own attendant catalogs. Time & Place: Los Angeles, 1957-1968 was exhibited in 2008-09 at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, and Los Angeles 1955-1985: The birth of an art capital at the Centre Pompidou in 2006. Both of these shows produced excellent catalogs. The Pompidou's, called Catalog L.A.: Birth of an Art Capital 1955-1985, is an obsessively detailed timeline of the entire era.

Beyond catalogs and monographs, there have been biographies (such as the Robert Irwin book mentioned above) and histories, including the excellent Rebels in Paradise: The Los Angeles Art Scene and the 1960s

by Hunter Drohojowska-Philp and the oral history compiled by Kristine McKenna, The Ferus Gallery: A Place to Begin

by Hunter Drohojowska-Philp and the oral history compiled by Kristine McKenna, The Ferus Gallery: A Place to Begin (as well as the documentary The Cool School: Story of the Ferus Art Gallery

(as well as the documentary The Cool School: Story of the Ferus Art Gallery by Morgan Neville). With all this, it would seem that another book on the L.A. art scene in the 1960s would be irrelevant. But there are always new details to unearth, and points of view not yet discussed.

by Morgan Neville). With all this, it would seem that another book on the L.A. art scene in the 1960s would be irrelevant. But there are always new details to unearth, and points of view not yet discussed.So even though I consider myself pretty much an expert on L.A. art in the 60s by now, I went ahead and ordered William Hackman's Out of Sight: The Los Angeles Art Scene of the Sixties. There isn't much here as far as the artists go that you won't find in Rebels in Paradise. But Hackman understood that institutions are important in a way that was only hinted at by Drohojowska-Philp. (That said, I consider Rebels in Paradise to be the superior book.) Obviously the rise and fall of one particular institution, the Ferus Gallery, is central to both books and any book dealing with L.A. in the 60s.

Artists outside the Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles, 1959. Clockwise from top: Billy Al Bengston, Irving Blum, Ed Moses, and John Altoon. Photo by William Claxton. - See more at: http://blogs.getty.edu/pacificstandardtime/explore-the-era/archives/i126/#sthash.eIk8NWu7.dpuf

To me it's an old story, but I realize my obsessions are not universal, so here's a nutshell history of the Ferus Gallery. In 1957, Walter Hopps and Edward Kienholz, two young men involved in the avant garde of the L.A. art scene, decided to partner up and open a gallery together on La Cienega Blvd., a commercial street in L.A. that already had several art galleries. They showed work by the cutting edge of L.A. and San Francisco art. But the gallery wasn't at all profitable, so in 1958, Irving Blum bought out Kienholz's share, moved the gallery across the street to a nicer space, trimmed the bloated roster and worked hard to turn Ferus into a gallery that made money for its artists and its owners. Blum gave Andy Warhol his first solo show and in general started showing more New York artist, as well as a very choice selection of L.A. artists. It has to be said that Kienholz, Hopps and Blum all had good eyes for art. Among their artists were people like Robert Irwin, Ed Moses, Ken Price, Ed Ruscha and Larry Bell. They really put Los Angeles art on the map at a time when art was utterly dominated by New York. In 1962, Walter Hopps left Ferus to take a job as a curator for the Pasadena Art Museum, and in 1967, Blum closed Ferus Gallery. It was just too hard to get collectors to part with their money for contemporary art in L.A. He moved to New York and started the Irving Blum Gallery. Of course, Hopps, Kienholz and Blum each achieved great success subsequent to the rise and fall of Ferus as an artist, as a curator/museum director, and as a gallerist respectively.

The Los Angeles County Museum on Fire, 1965–68, Ed Ruscha. Oil on canvas. 53 1/2 x 133 1/2 in.

But what Hackman also covers are some of the other institutions that formed the art ecology of L.A. in the 60s. The Los Angeles County Art Museum, for example, was founded in 1961 and moved into a large modernist structure on Wilshire Blvd. in 1965 (this new structure is the subject of Ed Ruscha's famous painting, The Los Angeles County Art Museum on Fire). The museum's board of directors were so self-serving that almost as soon as the museum was built, they fired museum director Richard Brown after he demanded that the museum be run more professionally (and not as a gallery for the board's art collections). This was followed by years of mediocrity.

Even more pathetic than LACMA was fate of the Pasadena Art Museum. After groundbreaking shows curated by Hopps, the museum board was convinced by Hopps that the museum should move into a custom built structure (it was housed in a leased mansion). Hopps had few allies on the museum board who, it was said by Hopps' predecessor Thomas Leavitt, cared more for "the quality of the parties" than the "quality of the exhibitions." (And that attitude persists in Houston as well, as a casual perusal of CultureMap confirms.) There was a split on the board between the older members (conservative Pasadena WASPS) and the newer members (liberal Westside Jews) about the type of art the museum should be dedicated to (the Westside contingent supporting a more modern approach, following in the success of Hopps' exhibits). Also, because the museum had long run on noblesse oblige, there was no institutional capacity to raise the money necessary to build a new building. Hopps was forced out and left L.A. for good. (He ended his career as director of the Menil.) By 1974, the Pasadena Museum was in such financial trouble that it was taken over by Norton Simon and became the Norton Simon Museum. Considering that it had been the vanguard museum for contemporary art for a few years, this was a terrible loss.

Art galleries also had their troubles. Ferus was just one of many galleries that closed in the late 60s in L.A. Their problem was similar to what Houston galleries face today--their potential customers would prefer to buy art in New York, which is only an airplane ride away. That was the situation at the end of the 70s--no commercial or public institutions could be counted on to support contemporary art in a reliable way in Los Angeles, despite the fact that that it was the third largest city in America.

This is where Creating the Future: Art and Los Angeles in the 1970s comes in. Like artists all over the U.S., by the 70s in Los Angeles, there were serious questions about the institutions. Aside from their failure to support L.A. art, it was dawning on artists that these places were sexist and racist as well. Michael Fallon shows how parallel art worlds developed through alternative subcultures in L.A. First is feminist, and the major catalyst here was Judy Chicago. After developing a feminist art program at Fresno State, she joined up with Miriam Schapiro at CalArts to continue this work. They founded "Womanhouse" in a mansion near downtown (far from CalArts's new Valencia campus).

That this came out of CalArts is not too surprising. It was established in 1961 when the Disney brothers merged the Chouinard Art Institute (where many of the "cool school" 60s generation of LA artists studied and taught) and the L.A. Conservatory of Music. They wanted a school that would churn out the kind of skilled artists, musicians and composers that the entertainment industry needed. CalArts is still a leader for teaching animation. But it really took off in unexpected directions in 1971, when it moved to its new campus in Valencia, a distant northern suburb of Los Angeles. The school hired people like Chicago, John Baldessari and Allen Kaprow to teach. Because of this, L.A. suddenly became a hotbed of both performance art and conceptual art. The artists they taught became some of the most important artists of the 70s and 80s--though few remained in Los Angeles. Baldessari in particular encouraged them to move to New York because he recognized it would be difficult for them to maintain careers in L.A.

Suzanne Lacy, Car Renovation, 1972

Much of the book deals with the spread of performance and conceptual art in L.A., focusing on artists like Chris Burden, Mike Kelley (whose career would blossom in the 80s, but the groundwork for which was laid in the 70s), Suzanne Lacy, Paul McCarthy, Bas Jan Ader and Allen Ruppersberg. This work seems somewhat divorced from the failed institutions of the 60s, but often connected with educational institutions for support. (I've always wondered if artists who wish to decommodify art through performance or ethereality don't see their art school salaries as another form of commodification. I do.)

Llyn Foulkes, Who's on Third?, 1971-73

But Fallon points out that painting continued in Los Angeles. So he pays attention to the heterogeneous painting of Llyn Foulkes, Vija Celmins, Robert Williams, etc., while correctly refusing to identify any school of painting in L.A. When Fallon identifies a trend or tendency, it tends to be self-defining (feminist art or Chicano art), or it is something he made up himself. For example, he names a group of artists "New Romantics"--artists who were attracted in one way or another to the dark side of Los Angeles. He places Paul McCarthy, Kelley, Terry Allen, Bettye Saar and Tony Oursler in this group (and Foulkes on its edge). This seems a little dubious, but many of these artists ended up in Helter Skelter: L.A. Art of the 1990s at MOCA, which had a similarly dark theme, so maybe he's right.

Fallon also looks at art that almost had no relationship to the art world. The mural movement in L.A. in the 70s was largely Chicano and largely existed outside the heavily theorized world of conceptual and performance art. It was unabashedly populist, for one thing, and highly political. But all art worlds overlap to one degree or another--Asco, the conceptualist Chicano collective was one such overlapping point. Likewise, Fallon includes a chapter on "Lowbrow" art, the art that evolved out of custom car, surf and skateboard culture. In the 70s, this work existed defiantly outside the mainstream artworld, but time heals all breaches--Mike Kelley and Jim Shaw persuaded curator Paul Schimmel to include Robert Williams, the leader of this school of art, in the Helter Skelter exhibit in 1992.

If it sounds like a lot of the artists in this book achieved notoriety after the 70s, that's true. The impression one gets reading Creating the Future is that artists spent the decade laying a groundwork for future success. This is true not only for Mike Kelley and Robert Williams, but for James Turrell, Vija Celmins and even John Baldessari.

Creating the Future is necessarily unfocused. The simple truth is that the number of artists and the variety of artists was going to necessarily be bigger than in the 1960s. That the art scene could be defined by one institution, the Ferus Gallery, in the 1960s was a highly unusual situation. I like that Fallon doesn't try to create any false connections between scenes and artists where none really exist. Los Angeles is a city big enough to contain multitudes, artistic tendencies that are in opposition to or orthogonal to other trends. I see this in Houston today, with cliques and styles that don't really exist for each other.

Chicago

Chicago differs greatly from Los Angeles in one important way. Its artists have never become central or important to contemporary art history in the way that some of Los Angeles' artists finally did. When I think of really well-known Chicago artists, I can only think of a few (for example, Leon Golub, Nancy Spero, Ed Paschke, Kerry James Marshal and Theaster Gates. And Golub and Spero were only rediscovered in the 80s, after long careers painting in Chicago). I think most people conversant with contemporary art might have heard of the Hairy Who without necessarily being able to name the artists involved. If they saw a Roger Brown painting or an H.C. Westermann sculpture, it might seem familiar. Here's a completely unscientific way of stating this imbalance. In my personal book collection, I have 21 books dealing with Los Angeles art and only seven dealing with Chicago art. And none of the seven are a general history like Out of Sight and Creating the Future. I would love to read such a book, if it existed.

That said, a new documentary, Hairy Who and the Chicago Imagists directed by Leslie Buchbinder, does try to fill in a few blanks. Right up front, it admits Chicago's marginality. "The story of 20th century American art is already written. It is not a story about Chicago." The subject of this film are a group of artists who started exhibiting in the 1960s. Most are completely unknown today, but a few--Jim Nutt, Karl Wirsum, Ed Paschke and Roger Brown have had major solo exhibits. They were all figurative painters. They weren't pop artists exactly, but they were influenced by popular culture, especially things on the fringe of popular culture. Instead of being influenced by shiny new products at the supermarket or mass-market ads, they were more likely to be influenced by the kinds of oddball items they found at flea markets or botanicas, early animated cartoons, pinball machines, carnival sideshows and painted commercial signs. But they were also influenced by outsider art and earlier Chicago artists like H.C. Westermann. Their work was often sexual and impolite--in this way, it seems similar to the contemporaneous art being produced by the underground cartoonists. One subgroup of the Chicago Imagists, the Hairy Who, even produced their own comic books to act as catalogs for their exhibits.

The structure of the film is to focus on one artist at a time, having that artist speak about his or her own work, and having other Imagists artists speak about their work, and then artists who were influenced by them. For instance, Kerry James Marshall and Chris Ware both conment on Jim Nutt's work, and Jeff Koons about Ed Paschke.

If Ferus is central to Out of Sight and CalArts to Creating the Future, the Hyde Park Art Center and the Phyllis Kind Gallery are the important institutions in Hairy Who and the Chicago Imagists. Don Baum was the director of the Hyde Park Art Center, and his stated goal was to give new artists a venue to show their work. Much of this was done through large group shows, but some artists wanted a smaller group show so that each of them could show multiple works. So Nutt, Suellen Rocca, Art Green, Gladys Nilsson and Jim Falconer proposed this to Baum. Baum suggested they include Karl Wirsum, which turned out to be an inspired addition. They brainstormed the name, Hairy Who, and it caught the attention of the public. (The name for the group makes them sound like a rock band, but they weren't a collective in the sense of making collective artworks--each artist did their own thing.)

They were so successful that they had two more shows together at the Hyde Park Art Center, and Baum realized that he had stumbled onto a good thing. Instead of having shows with dozens of artists, have shows with five or six artists and give them a slightly wacky name. The Nonplussed Some consisted of Ed Paschke, Ed Flood, Sarah Canright, Richard Wetzel, Robert Guinan and Don Baum, and it was followed by the False Image, consisting of Roger Brown, Christina Ramberg, Philip Hanson and Eleanor Dube.

Christina Ramberg, Head, 1969-70

Just as Baldessari was a key teacher for many of the 70s era LA artists (and artists who left LA), Ray Yoshida served the same role for 60s era imagists. One of his main messages was to collect things and fill your life with your collections. He wasn't talking about expensive art collections (although perhaps not excluding them), but accumulating objects that obsess you and that collectively come to define you. Ed Paschke had photos of circus freaks; Roger Brown and Karl Wirsum had collections of oddball objects; many of the Imagists collected things from the flea markets of Maxwell Street. Part of the Hairy Who's second exhibit was a glass case full of things they collected. This was for Yoshida the starting point for a person's art. All the Imagists are visual bricoleurs, finding subject matter in the strange stuff they found on the street. For instance, there is a section Christina Ramberg's diary where she talks of finding an old romance comic on Maxwell Street, seeing all these drawings of the protagonist from the rear and being inspired to paint a series based on them.

Ed Paschke, La Chanteuse, 1981

Phyllis Kind Gallery was founded in Chicago in 1967, and she became the primary gallery for many of these artists over the next decade. Jim Nutt remarks in the film that it was probably a mistake for so many of them to put all their eggs in that one basket, but Kind was aggressive in marketing their work. Over the course of the 70s, she was successful in placing the work with collectors and encouraging museums all over the world to show and collect the work. For instance, Walter Hopps curated a show of Chicago Imagists that originated in São Paulo and which traveled throughout Latin America. But like Irving Blum, she saw the writing on the wall and moved her operation to New York, shifting focus to outsider art. She says, "You do what you have to do when you have to do it."

As quickly as they found success, they became the reactionary establishment in the eyes of the younger Chicago artists who were influenced by conceptualism and theory. You could read the hostility towards them in the pages of the New Art Examiner, which started publishing in Chicago in 1973 and for years was another important institution on the local scene. In 1974, Frank Pannier wrote, "Here [in Chicago], through the continual re-hash of the same old tired 'Dada Surrealist' concepts and also through the constant proliferation of simple-minded provincial aesthetics, most 'pictorial' art is reduced to that infectious manifestation of visual gonorrhea most clearly typified by the 'Hairy Who?' and its many offspring." ("A Painter Reviews Chicago, Part 1," Frank Pannier, The New Art Examiner, Summer 1974)

It seemed that the Imagists had gone out of style. The art market rejected them, the critics forgot them, younger artists abjured them. But what comes around goes around and they seem to have come back, with recent exhibits at the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art (2011) and solo Jim Nutt exhibit at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago (2011). Karl Wirsum and Gladys Nilsson have relatively new gallery representation in New York City, and Philip Hanson's paintings were in the most recent Whitney Biennial (they were my favorite works in the show). The film concludes with a variety of contemporary artists talking about how important the work is to them, so their influence is strong even if these artists are still not well known outside Chicago.

Houston

In these two books and this documentary, one can see similarities to L.A. and Chicago in Houston's art scene. Houston is a younger city, of course. While there were interesting artists in Houston in the 1960s, it wasn't until the 70s that the local art scene took off. So where is a book or documentary film about that era in our city's art history? It's coming. A couple of weeks ago, Pete Gershon, author of Painting the Town Orange, gave a presentation on his work in progress, Pow Wow: Contemporary Artists Working in Houston, 1972-1985. He's been interviewing artists and people involved in Houston's art world for over a year now, since Bert Long's death in early 2013. Gershon had on a volunteer basis been cataloging Long's papers when Long suddenly died. Gershon said that even though he had spent a considerable amount of time with Long, there were still questions he wanted to ask. From there he realized that there are a number of Houston artists in their 60s, 70s and 80s about whom he could say the same thing. One thing lead to another, and this book was born. Rather than review something that doesn't yet exist except as a partially completed manuscript, I want to present a talk that Gershon gave about the work in progress at the Glassell school (filmed and edited by J.J. Avkah).

I believe regional art histories are extremely important. We feel sometimes that the modern world homogenizes culture, but the examples of L.A. and Chicago demonstrate how wrong that is--two cities in the U.S. produced utterly distinct art at exactly the same time. I should say three cities (including Houston). And each was distinct from New York. But this documentary and the two books also show how difficult it is to maintain and nurture a regional art scene. It can all go away and be forgotten, unless writers, archivists, film-makers and other keepers of memory do their work.