Robert Boyd

![]()

Charles Burns, X'ed Out, 2010

2010 saw the publication of X'ed Out![]() , the first major new work by Charles Burns since Black Hole

, the first major new work by Charles Burns since Black Hole![]() . Right away, the cover was promising--it was a pastiche of sorts of Hergé's The Shooting Star

. Right away, the cover was promising--it was a pastiche of sorts of Hergé's The Shooting Star![]() . Instead of setting it on a rocky shore, Burns set it in a grey, bombed out landscape. Burn's "Tintin" was a character drawn in a classic "realistic" comics style with a bandage on his head. But the pattern on the ovoid shape in the foreground was unmistakable--it was the same as the coloring of the mushroom in The Shooting Star.

. Instead of setting it on a rocky shore, Burns set it in a grey, bombed out landscape. Burn's "Tintin" was a character drawn in a classic "realistic" comics style with a bandage on his head. But the pattern on the ovoid shape in the foreground was unmistakable--it was the same as the coloring of the mushroom in The Shooting Star.

![]()

Hergé, The Shooting Star, 1942

The book opened with a decidedly surreal scene, drawn in a style that was a cross between Burns' own style and Hergé's--that is to say, the styles of two obsessive perfectionists. The main character looks like an older Tintin, with a black quiff instead of blonde. But the book quickly leaves this surreal scene behind to depict a realistic story of a young art student named Doug. There are some flashbacks and flash forwards--we readers don't really know when "now" is, but we do know Doug was a student in the early days of the punk rock era, and part of his art is a performance that he does involving wearing a depersonalizing Tintin-like mask, reading Burroughs-like cut-up texts and playing collages of noise from a cassette deck hanging from his neck. (He calls his performance persona "Nitnit.") We see him doing this performance to a group of largely indifferent viewers as the opening act of a punk band. It's here he meets Sarah, who becomes his lover.

![]()

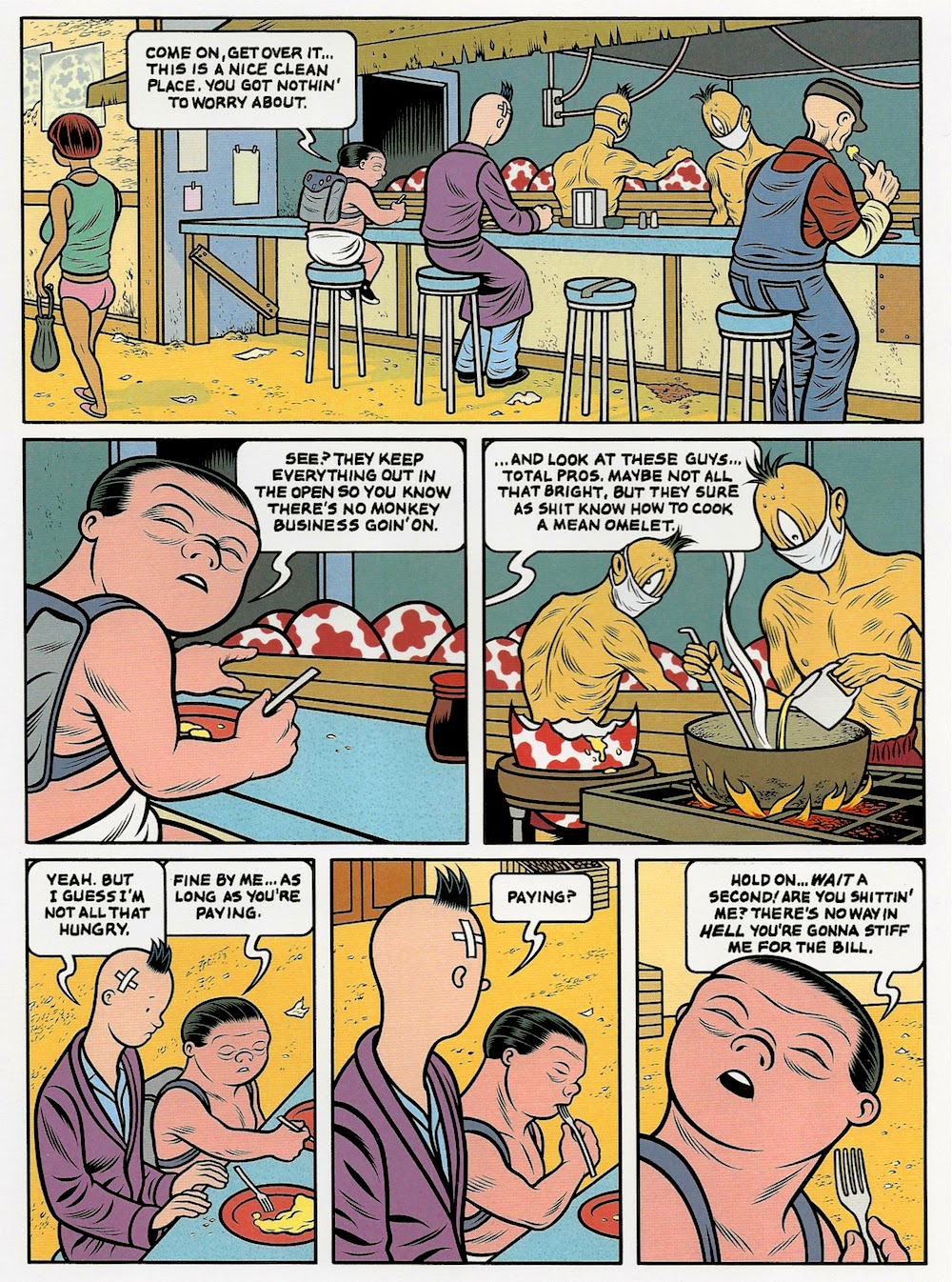

Charles Burns, X'D Out page 47, 2010

The link between the surreal fantasy world and Doug's world is obscure, but the main character in the surreal realm seems to be an analogue to Doug. The book was in color and published in a slightly oversize format, to deliberately mimic the format in Tintin. But unlike Tintin, the story wasn't neatly wrapped up in one volume. It was frustrating to reach the end because I knew it would be a long wait for the next volume.

![]()

Charles Burns, The Hive, 2012

Just as Black Hole was a book about adolescence, this series is about young adulthood. Burns seems aware in the same way that Jaime Hernandez was aware that people's bodies keep changing even after they become adults. In the second volume, The Hive![]() , we see Doug's future self talking about the past. He goes from being a slim student to packing on a few pounds. But the time he is with Sarah is when he seems to be a physical peak. They are a beautiful couple and his later self is full of regret about what happened to them, which he knows but we don't.

, we see Doug's future self talking about the past. He goes from being a slim student to packing on a few pounds. But the time he is with Sarah is when he seems to be a physical peak. They are a beautiful couple and his later self is full of regret about what happened to them, which he knows but we don't.

![]()

Chales Burns, The Hive page 32, two bottom tiers, 2012

In the surreal world, the Doug analogue meets an equivalent to Sarah--she is a breeder in the Hive. The connections between the two stories seems to get stronger in The Hive, but they still seem mostly unconnected.

![]()

Charles Burns, Sugar Skull, 2014

Sugar Skull![]() , which just came out, completes the story. All the flashbacks and disconnected episodes in Doug's life coalesce, and the parallel Burns-Hergé world makes sense as well. If there is any fault here, it's that everything is tied up a little too neat. But I found it satisfying. Doug turns out to be a pretty imperfect guy who stumbles badly as he transitions into adulthood and leaves behind some unrepairable wreckage. This is the kind of story an older person can tell convincingly. Burns was born in 1955. I wrote in an earlier post about how sad I feel about comics artists I've admired who, over time, drop out of the comics field. One reason I regret them leaving is that they will never tell stories from the point of view of full maturity. It is Burns' 59 years on this planet that give him the perspective to produce X'ed Out,The Hive and Sugar Skull. These books bring together the obsessions of his earliest work with an emotional maturity those works, as brilliant as they were, lacked.

, which just came out, completes the story. All the flashbacks and disconnected episodes in Doug's life coalesce, and the parallel Burns-Hergé world makes sense as well. If there is any fault here, it's that everything is tied up a little too neat. But I found it satisfying. Doug turns out to be a pretty imperfect guy who stumbles badly as he transitions into adulthood and leaves behind some unrepairable wreckage. This is the kind of story an older person can tell convincingly. Burns was born in 1955. I wrote in an earlier post about how sad I feel about comics artists I've admired who, over time, drop out of the comics field. One reason I regret them leaving is that they will never tell stories from the point of view of full maturity. It is Burns' 59 years on this planet that give him the perspective to produce X'ed Out,The Hive and Sugar Skull. These books bring together the obsessions of his earliest work with an emotional maturity those works, as brilliant as they were, lacked.

I like seeing older cartoonists take this kind of material on, as Mimi Pond did in Over Easy![]() . The health of comics as an art form depends on having several generations of serious comics artists working simultaneously.

. The health of comics as an art form depends on having several generations of serious comics artists working simultaneously.

![]()

Dylan Horrocks, Incomplete Works, 2014

One of my favorite cartoonists is Dylan Horrocks. Born in 1966, he could be lumped in with a group of English, Australian, Canadian and New Zealand small press cartoonists whose work was quite sensitive, small scale and occasionally verged on twee. I'm thinking of artists like Eddie Campbell, Glenn Dakin, Ed Pinsent, etc., who were associated with the U.K. small press movement in the 80s and Escape Magazine as well as Fox Comics in Australia. Eddie Campbell and Dylan Horrocks are the two most successful of that group, but they all were interesting and they collectively offered an alternative to the dominant modes of alternative comics-making that came along in the 80s--the punk-inflected experimental work of the Raw artists (including Charles Burns), the sarcastic post-underground wise-ass work of Peter Bagge, Dan Clowes and many of the Weirdo artists, and the un-self-pitying autobiographical comics of Chester Brown and many Canadian cartoonists.

Horrocks is willing to mix autobiography into his work, which helps to ground his flights of fancy, but his great subject is comics itself. That's what comes through in story after story in Incomplete Works![]() , a collection of stories from 1986 to 2012. I've read many of these stories before in the various ephemeral publications where they first ran, but it quite astonishing to see them in one place. It is interesting to see how constant his themes and subjects have remained over the course of almost 30 years of work.

, a collection of stories from 1986 to 2012. I've read many of these stories before in the various ephemeral publications where they first ran, but it quite astonishing to see them in one place. It is interesting to see how constant his themes and subjects have remained over the course of almost 30 years of work.

![]()

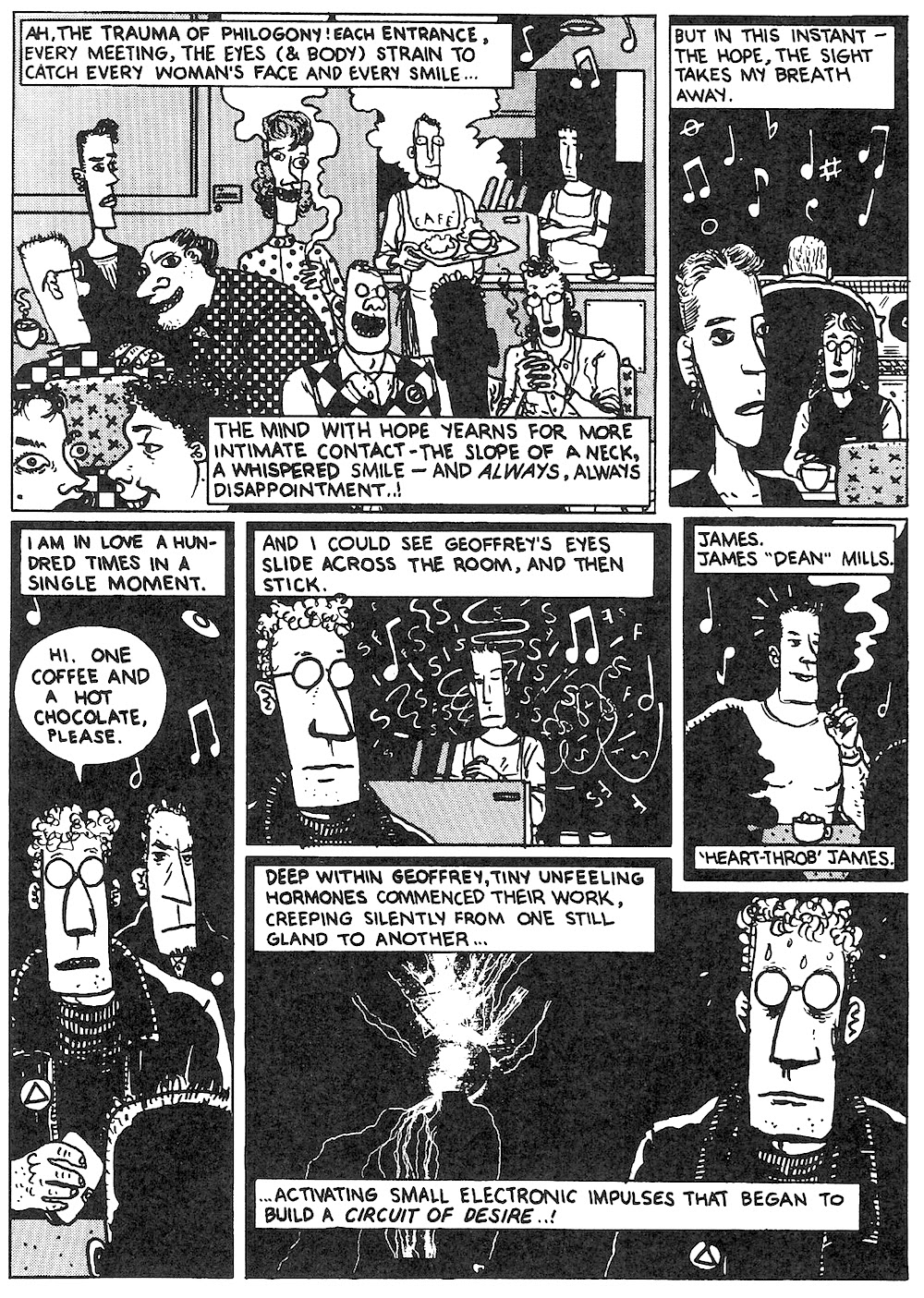

Dylan Horrocks, "Little Death" page 2, 1986

His early work shows him searching for style, but his drawing seems very self-assured. The page above is from "Little Death," drawn when Horrocks was 20 years old. A story of sexual desire in dark public places, Horrocks notes that he met his partner, Terry Fleming, while working on it. It's almost proof of the old Jay Lynch theory--you get what you draw!

Like many artists from New Zealand, Horrocks moved to London for a while to try to make a go of it. And his feeling of alienation and home-sickness there inform a lot of work in the early parts of this anthology, including a masterpiece called "The Last Fox Story." In his endnotes, Horrocks writes that he drew it in ballpoint pen on memo paper. He was working in a bookstore in London and having serious doubts about his vocation as a cartoonist. The story was intended for the final issue of Fox, an long-running alternative comics magazine from Melbourne, Australia. The fact that Fox was coming to an end may have suggested to Horrocks that there wasn't a place for the kind of quiet, contemplative comics he drew.

![]()

Dylan Horrocks, "The Last Fox Story" page 18, 1990

He humorously portrays his dilemma in the story as a fear of comics, but what he's really talking about is that moment of crisis that hits young artists of all stripes--can he carry on? Is there a place for his work? Is he capable? Horrocks tells this story about comics using comics, but it seems quite universal. All artists face this, often at the same age as Horrocks did. As we know, many in his place say no--they decide to turn their life in a different direction. But as you read Incomplete Works, you know what Horrocks chose. He kept on going and started his own solo comic book, Pickle, in 1992. It was here he serialized one of the best graphic novels ever, Hicksville![]() . (Full disclosure--I own two pages from this work.) And you can see his mastery of this art form blossom during the 90s in the stories here.

. (Full disclosure--I own two pages from this work.) And you can see his mastery of this art form blossom during the 90s in the stories here.

![]()

Dylan Horrocks, "A Cartoonist's Diary" page 12, 2012

It all comes full circle in the last story in the volume, "A Cartoonist's Diary," which was published online by the Comics Journal. His interests and concerns in 2012 as a 46-year-old man are not all that different than the 24-year-old who drew "The Last Fox Story," but now he is a teacher, an elder figure with an impressive body of work behind him. What I love about his art is that it is so humane and humble. He seems to see himself as part of a world-wide comics history. He reveres his predecessors, both famous (a little story about George Herriman) and obscure (a biographical strip about New Zealand underground cartoonist Barry Linton).

His next graphic novel, Sam Zabel And The Magic Pen![]() , will be published later this year, and you can read most of it online right now at Horrock's website Hicksville Comics. The Magic Pen is great, as is Hicksville. But Incomplete Works is, I think, their equal. It's a moving, poetic collection of work.

, will be published later this year, and you can read most of it online right now at Horrock's website Hicksville Comics. The Magic Pen is great, as is Hicksville. But Incomplete Works is, I think, their equal. It's a moving, poetic collection of work.

- Three books by Charles Burns

Charles Burns, X'ed Out, 2010

2010 saw the publication of X'ed Out

, the first major new work by Charles Burns since Black Hole

, the first major new work by Charles Burns since Black Hole . Right away, the cover was promising--it was a pastiche of sorts of Hergé's The Shooting Star

. Right away, the cover was promising--it was a pastiche of sorts of Hergé's The Shooting Star . Instead of setting it on a rocky shore, Burns set it in a grey, bombed out landscape. Burn's "Tintin" was a character drawn in a classic "realistic" comics style with a bandage on his head. But the pattern on the ovoid shape in the foreground was unmistakable--it was the same as the coloring of the mushroom in The Shooting Star.

. Instead of setting it on a rocky shore, Burns set it in a grey, bombed out landscape. Burn's "Tintin" was a character drawn in a classic "realistic" comics style with a bandage on his head. But the pattern on the ovoid shape in the foreground was unmistakable--it was the same as the coloring of the mushroom in The Shooting Star.Hergé, The Shooting Star, 1942

The book opened with a decidedly surreal scene, drawn in a style that was a cross between Burns' own style and Hergé's--that is to say, the styles of two obsessive perfectionists. The main character looks like an older Tintin, with a black quiff instead of blonde. But the book quickly leaves this surreal scene behind to depict a realistic story of a young art student named Doug. There are some flashbacks and flash forwards--we readers don't really know when "now" is, but we do know Doug was a student in the early days of the punk rock era, and part of his art is a performance that he does involving wearing a depersonalizing Tintin-like mask, reading Burroughs-like cut-up texts and playing collages of noise from a cassette deck hanging from his neck. (He calls his performance persona "Nitnit.") We see him doing this performance to a group of largely indifferent viewers as the opening act of a punk band. It's here he meets Sarah, who becomes his lover.

Charles Burns, X'D Out page 47, 2010

The link between the surreal fantasy world and Doug's world is obscure, but the main character in the surreal realm seems to be an analogue to Doug. The book was in color and published in a slightly oversize format, to deliberately mimic the format in Tintin. But unlike Tintin, the story wasn't neatly wrapped up in one volume. It was frustrating to reach the end because I knew it would be a long wait for the next volume.

Charles Burns, The Hive, 2012

Just as Black Hole was a book about adolescence, this series is about young adulthood. Burns seems aware in the same way that Jaime Hernandez was aware that people's bodies keep changing even after they become adults. In the second volume, The Hive

, we see Doug's future self talking about the past. He goes from being a slim student to packing on a few pounds. But the time he is with Sarah is when he seems to be a physical peak. They are a beautiful couple and his later self is full of regret about what happened to them, which he knows but we don't.

, we see Doug's future self talking about the past. He goes from being a slim student to packing on a few pounds. But the time he is with Sarah is when he seems to be a physical peak. They are a beautiful couple and his later self is full of regret about what happened to them, which he knows but we don't.

Chales Burns, The Hive page 32, two bottom tiers, 2012

In the surreal world, the Doug analogue meets an equivalent to Sarah--she is a breeder in the Hive. The connections between the two stories seems to get stronger in The Hive, but they still seem mostly unconnected.

Charles Burns, Sugar Skull, 2014

Sugar Skull

, which just came out, completes the story. All the flashbacks and disconnected episodes in Doug's life coalesce, and the parallel Burns-Hergé world makes sense as well. If there is any fault here, it's that everything is tied up a little too neat. But I found it satisfying. Doug turns out to be a pretty imperfect guy who stumbles badly as he transitions into adulthood and leaves behind some unrepairable wreckage. This is the kind of story an older person can tell convincingly. Burns was born in 1955. I wrote in an earlier post about how sad I feel about comics artists I've admired who, over time, drop out of the comics field. One reason I regret them leaving is that they will never tell stories from the point of view of full maturity. It is Burns' 59 years on this planet that give him the perspective to produce X'ed Out,The Hive and Sugar Skull. These books bring together the obsessions of his earliest work with an emotional maturity those works, as brilliant as they were, lacked.

, which just came out, completes the story. All the flashbacks and disconnected episodes in Doug's life coalesce, and the parallel Burns-Hergé world makes sense as well. If there is any fault here, it's that everything is tied up a little too neat. But I found it satisfying. Doug turns out to be a pretty imperfect guy who stumbles badly as he transitions into adulthood and leaves behind some unrepairable wreckage. This is the kind of story an older person can tell convincingly. Burns was born in 1955. I wrote in an earlier post about how sad I feel about comics artists I've admired who, over time, drop out of the comics field. One reason I regret them leaving is that they will never tell stories from the point of view of full maturity. It is Burns' 59 years on this planet that give him the perspective to produce X'ed Out,The Hive and Sugar Skull. These books bring together the obsessions of his earliest work with an emotional maturity those works, as brilliant as they were, lacked.I like seeing older cartoonists take this kind of material on, as Mimi Pond did in Over Easy

. The health of comics as an art form depends on having several generations of serious comics artists working simultaneously.

. The health of comics as an art form depends on having several generations of serious comics artists working simultaneously.- The History of Dylan Horrocks

Dylan Horrocks, Incomplete Works, 2014

One of my favorite cartoonists is Dylan Horrocks. Born in 1966, he could be lumped in with a group of English, Australian, Canadian and New Zealand small press cartoonists whose work was quite sensitive, small scale and occasionally verged on twee. I'm thinking of artists like Eddie Campbell, Glenn Dakin, Ed Pinsent, etc., who were associated with the U.K. small press movement in the 80s and Escape Magazine as well as Fox Comics in Australia. Eddie Campbell and Dylan Horrocks are the two most successful of that group, but they all were interesting and they collectively offered an alternative to the dominant modes of alternative comics-making that came along in the 80s--the punk-inflected experimental work of the Raw artists (including Charles Burns), the sarcastic post-underground wise-ass work of Peter Bagge, Dan Clowes and many of the Weirdo artists, and the un-self-pitying autobiographical comics of Chester Brown and many Canadian cartoonists.

Horrocks is willing to mix autobiography into his work, which helps to ground his flights of fancy, but his great subject is comics itself. That's what comes through in story after story in Incomplete Works

, a collection of stories from 1986 to 2012. I've read many of these stories before in the various ephemeral publications where they first ran, but it quite astonishing to see them in one place. It is interesting to see how constant his themes and subjects have remained over the course of almost 30 years of work.

, a collection of stories from 1986 to 2012. I've read many of these stories before in the various ephemeral publications where they first ran, but it quite astonishing to see them in one place. It is interesting to see how constant his themes and subjects have remained over the course of almost 30 years of work.

Dylan Horrocks, "Little Death" page 2, 1986

His early work shows him searching for style, but his drawing seems very self-assured. The page above is from "Little Death," drawn when Horrocks was 20 years old. A story of sexual desire in dark public places, Horrocks notes that he met his partner, Terry Fleming, while working on it. It's almost proof of the old Jay Lynch theory--you get what you draw!

Like many artists from New Zealand, Horrocks moved to London for a while to try to make a go of it. And his feeling of alienation and home-sickness there inform a lot of work in the early parts of this anthology, including a masterpiece called "The Last Fox Story." In his endnotes, Horrocks writes that he drew it in ballpoint pen on memo paper. He was working in a bookstore in London and having serious doubts about his vocation as a cartoonist. The story was intended for the final issue of Fox, an long-running alternative comics magazine from Melbourne, Australia. The fact that Fox was coming to an end may have suggested to Horrocks that there wasn't a place for the kind of quiet, contemplative comics he drew.

Dylan Horrocks, "The Last Fox Story" page 18, 1990

He humorously portrays his dilemma in the story as a fear of comics, but what he's really talking about is that moment of crisis that hits young artists of all stripes--can he carry on? Is there a place for his work? Is he capable? Horrocks tells this story about comics using comics, but it seems quite universal. All artists face this, often at the same age as Horrocks did. As we know, many in his place say no--they decide to turn their life in a different direction. But as you read Incomplete Works, you know what Horrocks chose. He kept on going and started his own solo comic book, Pickle, in 1992. It was here he serialized one of the best graphic novels ever, Hicksville

. (Full disclosure--I own two pages from this work.) And you can see his mastery of this art form blossom during the 90s in the stories here.

. (Full disclosure--I own two pages from this work.) And you can see his mastery of this art form blossom during the 90s in the stories here.

Dylan Horrocks, "A Cartoonist's Diary" page 12, 2012

It all comes full circle in the last story in the volume, "A Cartoonist's Diary," which was published online by the Comics Journal. His interests and concerns in 2012 as a 46-year-old man are not all that different than the 24-year-old who drew "The Last Fox Story," but now he is a teacher, an elder figure with an impressive body of work behind him. What I love about his art is that it is so humane and humble. He seems to see himself as part of a world-wide comics history. He reveres his predecessors, both famous (a little story about George Herriman) and obscure (a biographical strip about New Zealand underground cartoonist Barry Linton).

His next graphic novel, Sam Zabel And The Magic Pen

, will be published later this year, and you can read most of it online right now at Horrock's website Hicksville Comics. The Magic Pen is great, as is Hicksville. But Incomplete Works is, I think, their equal. It's a moving, poetic collection of work.

, will be published later this year, and you can read most of it online right now at Horrock's website Hicksville Comics. The Magic Pen is great, as is Hicksville. But Incomplete Works is, I think, their equal. It's a moving, poetic collection of work.